By Timothy Holtgrefe December 2022 For several years prior to Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, President Vladimir Putin had devoted much of his time and effort to promoting false narratives and a revisionist history of Ukraine as early as 2005. However, the rhetorical gaslighting and denial of Ukraine’s rich cultural heritage is actually nothing new. In fact for Russian autocrats it is an historical continuity going back several hundred years in an effort to subjugate a race of people. |  Image credit: reuters/Carlos Barria |

What is surprising is not that the Russian Empire ‘russified’ their ethnic minorities, as all colonizers have performed similar practices, but that so many of these false narratives continue to persist into today’s political discourse regarding the current war in Ukraine; even in the West. This is part 2 of an HQ exclusive series to investigate Russia’s relentless attack on history. In this episode, we will explore the aftermath of Catherine the Great’s complete occupation of Ukraine in 1793.

Survival Under Tsarist Russification

In stark contrast to Vladimir Putin’s claim that Russians and Ukrainians are “one people,” Tsars and Soviet premiers have historically done their best to both russify and repress Ukrainian cultural identity. When Kyiv fell under Russian occupation in 1793, Ukrainians were able to retain much of their native language and cultural

In stark contrast to Vladimir Putin’s claim that Russians and Ukrainians are “one people,” Tsars and Soviet premiers have historically done their best to both russify and repress Ukrainian cultural identity. When Kyiv fell under Russian occupation in 1793, Ukrainians were able to retain much of their native language and cultural

| expression through the arts such as poetry, newspapers, and storytelling. Cossack traditions, collections of rich peasant folklore, and development of Ukrainian as a literary language – all began to flourish in the early 1800s. The initial center was Kharkiv University (founded in 1805), with Kyiv’s St. Vladimir’s University (1835) shortly after. These universities preserved Ukrainian identity and encapsulated Ukrainian history from russification. Works such as Istoriia Rusov’s History of Rus (1846) glorified and romanticized the Cossak past and |

viewed Ukrainians as a separate people deserving of self-government. Ukraine, it argued, not Russia, was the lineal descendant of Kievan Rus. Ukrainian poets such as Taras Shevchenko, fervently opposed tsarist Russian autocracy, praised Cossack leaders who had opposed Russian rule, and advocated Ukrainian self-determination.

However, these ideologies were too dangerous for the empire’s continued control of Ukraine and its rich agricultural land. Tsar Nicholas I (1825-55) promptly arrested Ukraine’s literary society and other Ukrainian academics he deemed a threat to Russia’s revisionist mythology (see Part I). His successor, Alexander II (1855-81), intensified his father’s russification policy towards his empire’s European borderlands such as Finland, Poland, and Ukraine. Their languages were forbidden from being spoken in schools even in their native territories. Ukrainian poets such as Shevchenko and owners of Ukrainian newspapers were exiled to Siberia. According to historians MacKenzie & Curran (2002):

Worried by a rising Ukrainian national consciousness, St. Petersburg authorities… [introduced] a total prohibition on importing and publishing Ukrainian books, on using Ukrainian on stage, or on teaching in the language. May 1876, Alexander II issued the Ems Decree, which crippled Ukrainophile activities and closed Kiev’s branch of the Geographical Society. Crushed in Russia, Ukrainian national activities flourished in freer Austrian Galicia, which emerged as a nucleus for a Ukrainian nation (pp.308).

Soon after the crackdown, the Interior Minister P. A. Valuev pontificated that Ukrainian language “has never existed, does not exist, and shall never exist” (cited by Subtelny, 1988).

Worried by a rising Ukrainian national consciousness, St. Petersburg authorities… [introduced] a total prohibition on importing and publishing Ukrainian books, on using Ukrainian on stage, or on teaching in the language. May 1876, Alexander II issued the Ems Decree, which crippled Ukrainophile activities and closed Kiev’s branch of the Geographical Society. Crushed in Russia, Ukrainian national activities flourished in freer Austrian Galicia, which emerged as a nucleus for a Ukrainian nation (pp.308).

Soon after the crackdown, the Interior Minister P. A. Valuev pontificated that Ukrainian language “has never existed, does not exist, and shall never exist” (cited by Subtelny, 1988).

| It is important to note that these restrictions of Ukrainian cultural expression and arrests were followed by revisionist Russian history and gaslighting of Ukrainians. Not only could Ukrainian’s not learn their own history or speak their language, they were taught in schools that Ukraine was always part of Russia and that Russians and Ukrainians were one people. All of these activities define the term cultural genocide and have continued into the present. As a result, both Russians and some Ukrainians today have a distorted view of history with respect to their own historical identity. After centuries of cultural |

suppression and revisionist history taught in schools, many do not know Ukraine’s history as separate or unique from Russia in spite of their roughly 500 years of independent history, different language and alphabet. Unfortunately this cultural genocide is what is necessary for empires to exist. It is a byproduct of imperialism that the Kremlin still finds useful today.

School Textbooks Today

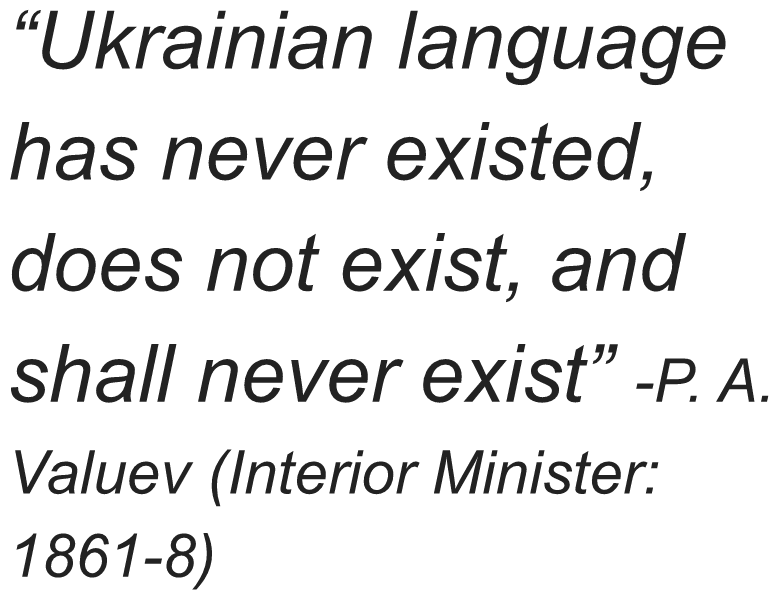

After Mikail Gorbachev’s reforms of Glasnost and Perestroika, and the subsequent collapse of the Soviet Union; Russian history textbooks took on several liberal reforms after 1994 which included critical analysis of Stalin’s reign of terror and honest critique of crimes committed by the Soviet Union. However, once Vladimir Putin came to power in the new Russian Federation, these reforms were reversed. According to Korostelina (2010), Putin’s regime took on stricter controls over how history was taught in schools especially after the seventh edition of National history: 20th century authored by Igor Dolutsky (2002) asked students to analyze Putin’s presidency and if they thought Russia was drifting towards a police state. The reaction of President Putin was extremely negative. He stressed that history education should emphasize great achievement of the nation and not its mistakes or wrong actions, pointing out that history textbooks “should inculcate a feeling of pride for one’s country” (Obrazovanie, 2002 cited by Korostelina, 2010). Since 2003, the list of approved textbooks has been drawn up by the Department of State Policy and Legal Regulation in the Sphere of Education. Detailed history curricula are approved at the national level. Needless to say, textbooks in Russian schools today promote strong Russian nationalism, provide little to no analysis of Russia’s subjugation and colonization of Ukraine, which in turn provides zero context for current events outside state media.

After Mikail Gorbachev’s reforms of Glasnost and Perestroika, and the subsequent collapse of the Soviet Union; Russian history textbooks took on several liberal reforms after 1994 which included critical analysis of Stalin’s reign of terror and honest critique of crimes committed by the Soviet Union. However, once Vladimir Putin came to power in the new Russian Federation, these reforms were reversed. According to Korostelina (2010), Putin’s regime took on stricter controls over how history was taught in schools especially after the seventh edition of National history: 20th century authored by Igor Dolutsky (2002) asked students to analyze Putin’s presidency and if they thought Russia was drifting towards a police state. The reaction of President Putin was extremely negative. He stressed that history education should emphasize great achievement of the nation and not its mistakes or wrong actions, pointing out that history textbooks “should inculcate a feeling of pride for one’s country” (Obrazovanie, 2002 cited by Korostelina, 2010). Since 2003, the list of approved textbooks has been drawn up by the Department of State Policy and Legal Regulation in the Sphere of Education. Detailed history curricula are approved at the national level. Needless to say, textbooks in Russian schools today promote strong Russian nationalism, provide little to no analysis of Russia’s subjugation and colonization of Ukraine, which in turn provides zero context for current events outside state media.

| Additionally, this control of Russian history textbooks was further used to promote Putin’s attempts to reassert dominance in Ukraine through positions of Russian linguistic education and science during the pro-Russian presidency of Viktor Yanukyvich as a neo-Imperial discourse. Prior to Yanukyvich’s removal in 2014, in particular, Dmytro Tabachnyk, who served as Vice Prime Minister of Ukraine in 2002–2005, 2006–2007, and in 2010–2014 as the Minister of Education and Science of Ukraine, all actively implemented ideology in Ukraine of the basic principles of the “Russian World.” He noted, among |

other things, that the unity of the Slavic world, the preservation of its identity, and its successful competition with the German world directly depends on the strength and unity of the “Russian World” – in fact only “a large Russian nation, which includes in itself the Great Russians, the Little Russians and Byelorussians, have not disappeared yet” (cited by Hai-Nyzhnyk et al 2018).

Thus, in Ukraine, the ex-minister of education and science, D.Tabachnyk, had a special place in strengthening the influence Vladimir Putin’s regime had on Ukraine’s Russian language speakers and promoting the ideas of the “Russian World” by supplying Russian textbooks to Ukraine’s communities and schools. These textbooks served to undermine the sense of Ukrainian identity and promote “Russian World” ideology. In an interview with the Russian radio station Echo of Moscow, in particular, Tabachnyk talked about his decisive role in ensuring the printing of school textbooks in Russian with funds from the state budget of Ukraine, expanding the scope of studying Russian literature in Ukrainian schools. As Hai-Nyzhnyk et al 2018 conclude:

Thus, for a long time, the Russian Federation actively implemented ideas and principles of the “Russian world” in the spiritual, informational, linguistic, cultural, educational and scientific space of Ukraine, which ultimately led to the weakening of the Ukrainian state, the Ukrainian nation and the national identity (Hai-Nyzhnyk et al 2018).

In summary, Ukraine and Ukrainians, beyond their will, were included in the ideological concept of the “Russian World” with all the unpredictable consequences for them; namely the initial “fraternal” cooperation, the gradual “soft” absorption, the time-stretched full assimilation, and the final elimination of Ukraine and Ukrainians as a

Thus, for a long time, the Russian Federation actively implemented ideas and principles of the “Russian world” in the spiritual, informational, linguistic, cultural, educational and scientific space of Ukraine, which ultimately led to the weakening of the Ukrainian state, the Ukrainian nation and the national identity (Hai-Nyzhnyk et al 2018).

In summary, Ukraine and Ukrainians, beyond their will, were included in the ideological concept of the “Russian World” with all the unpredictable consequences for them; namely the initial “fraternal” cooperation, the gradual “soft” absorption, the time-stretched full assimilation, and the final elimination of Ukraine and Ukrainians as a

| sovereign state and a distinct nation. Any attempts by the Ukrainian government to reverse this course or limit widespread use of these textbooks and literature promoting the “Russian World” were countered with cries from the Kremlin and their pro-Russian backers of ‘russophobia’ and alleged persecution of Ukraine’s Russian speakers. |

After invading Ukraine in 2022, the Kremlin has wasted no time in sending teachers and textbooks to instruct Ukrainian children in the new Russian curriculum that removes nearly all references to Ukraine and Kyiv, even renaming the medieval kingdom of Kievan Rus to just “Rus” or “Old Rus” (Devlin & Korenyuk, 2022). Inside Russia, teachers have been prosecuted and silenced for even taking moderate positions on the Ukraine conflict. Yelena Bagaeva from Buryatia in eastern Siberia was fined 40,000 rubles when she told her students that they “can't wish death on Ukrainians and hate them, they are people like us” (Strozewski, 2022).

The cultural genocide and erasure of history continues. One may conclude that not only has the russification and gaslighting of Ukrainians continued well after independence from Russia was achieved in 1991, these efforts have never ceased and are part of a wider geopolitical strategy dating back to tsarist imperialism.

The cultural genocide and erasure of history continues. One may conclude that not only has the russification and gaslighting of Ukrainians continued well after independence from Russia was achieved in 1991, these efforts have never ceased and are part of a wider geopolitical strategy dating back to tsarist imperialism.

Putin’s Tsarist Foreign Policy

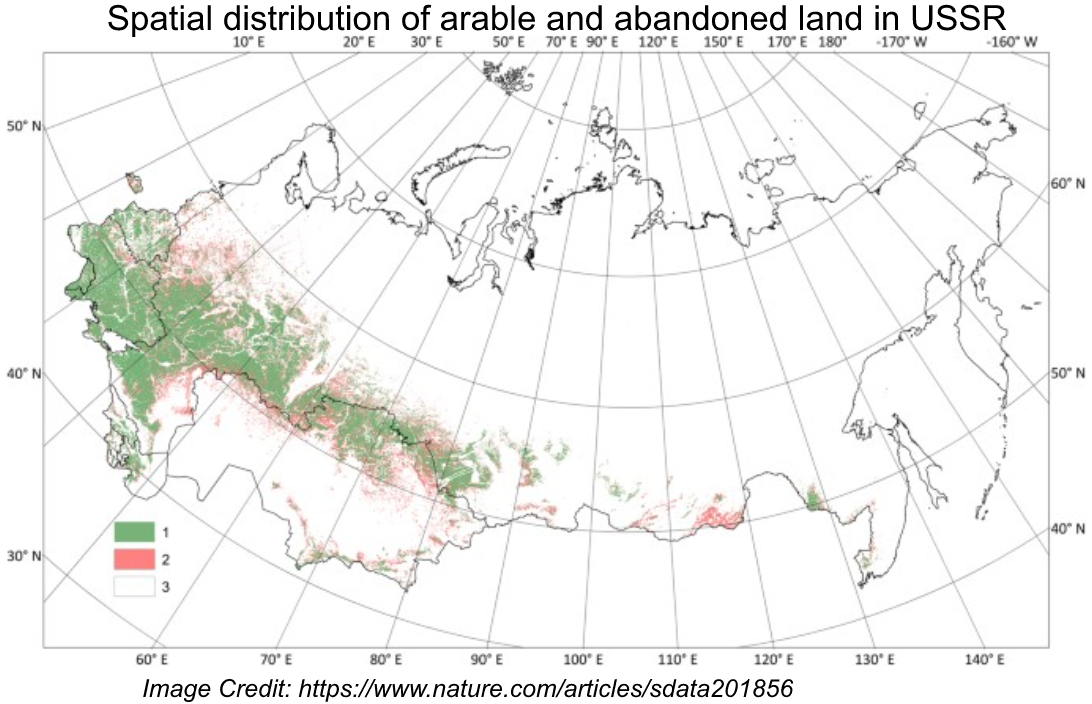

As covered in Part I of this series, Tsarist Russia pushed the Third Rome Theory in order to promote its imperial ambitions to acquire not only territories of Ukraine, but envisioned the Balkans and Turkish Straits as well. Although Russia has occupied a greater land mass than any nation state in the world, its existing territories have

As covered in Part I of this series, Tsarist Russia pushed the Third Rome Theory in order to promote its imperial ambitions to acquire not only territories of Ukraine, but envisioned the Balkans and Turkish Straits as well. Although Russia has occupied a greater land mass than any nation state in the world, its existing territories have

| lacked fertile soil for agriculture and warm water ports vital for international commerce. To promote Russia as the Third Rome through soft diplomacy, Tsars increasingly used Pan-Slavanist ideology with a divine zeal. By framing Tsarist leaders as guardians of Christian Orthodoxy, the Russian Empire frequently meddled in the internal politics of its neighbors by pursuing treaties that granted itself “protectors'' of Orthodox Christian minorities throughout the Ottoman |

Empire’s Balkin provinces, particularly near the strategic Bosphorus Strait that links the Mediterranean Sea to the Black Sea. Whether real or imagined, Russia would use its “protector” status to invade territories near strategic regions to “save” them from their Turkish oppressors, push for independence of Balkan provinces, and/or annex said territories as part of “Holy Russia.” 1827 would see the first of many conflicts between the Turks and Russia, each time ending in more Black Sea coast line ceded to Russia and more undefined rights to “protect” Orthodox Christians living in the Ottoman as well as AustroHungarian Empires.

Direct military aid to the Ottoman Empire’s Balkin separatists began as early as the 1860s to encourage such provinces as Serbia to rebel against the Turks. Around Serbia formed the Balkan League, including Greece and

Direct military aid to the Ottoman Empire’s Balkin separatists began as early as the 1860s to encourage such provinces as Serbia to rebel against the Turks. Around Serbia formed the Balkan League, including Greece and

| Montenegro, which was supplied with arms by the Russian War Ministry. The projection of Russian Pan-Slavism presented Russia as the superior “big brother” for Slav brethren of the west and south under “foreign” rule. Russian elites, military leaders, and prominent writers, including Fedor Dostoensky, expounded Pan-Slav doctrines that stimulated sympathy among educated Russians for Slavs living in Ottoman Turkey and Austria Hungary. N. I. Danilevskii’s Russia and Europe (1872), sometimes |

referred to as the “Bible” of Pan-Slavism, predicted Slav triumph in an “inevitable conflict” with Europe and the formation of an all-Slav federation centering in Constantinople. R. A. Fadeev, a retired major general, proclaimed in 1869, Russia’s historic mission was to lead Orthodox Slavs in war against the Germans until “the Russian reigning house covers the liberated soil of Eastern Europe with its branches under the supremacy of the tsar of Russia” (Cited by MacKenzie & Curran, 2002). In July 1875 Orthodox Serbs in the Turkish provinces of Hercegovina and Bosnia revolted and were supported, at first unofficially, by Serbia, Montenegro, and Russian Slav committees. Pan-Slav general M. G. Cherniaev was sent to direct Serbia’s armies and recruited several thousand Russian volunteers to serve under him. To the Russian public, he sold an image of unselfish Russian aid to the cause of Slav liberation, though he and his officers “sought to transform Serbia into a Russian satellite” (pp.334).

Eventually Pan-Slav agitation drew Russia into the costly Russo-Turkish War of 1877-78. Russia’s success in the conflict imposed upon the Turks a treaty which envisioned a Big Bulgaria under Russian Military occupation. Fearing this move was a yet another precursor to expand even farther to capture Constantinople and the straits, Britain and Austria threatened war with Russia if these terms were realized and forced the Tsar to accept co-occupation of the Balkans with Austria Hungary – setting the stage for World War I (MacKenzie & Curran, 2002).

Today, Vladimir Putin has reintroduced tsarist Pan-Slavism into much of his foreign policy and tactics for justifying Russian expansion into Europe. Using the same familiar language, Putin portrays Russia as a protector of Russian Orthodox people living in foreign lands once under its sphere of influence, or the “Russian World.” By

Today, Vladimir Putin has reintroduced tsarist Pan-Slavism into much of his foreign policy and tactics for justifying Russian expansion into Europe. Using the same familiar language, Putin portrays Russia as a protector of Russian Orthodox people living in foreign lands once under its sphere of influence, or the “Russian World.” By

| exaggerating or outright inventing injustices against ethnic Russians living in Ukraine, Putin has justified his actions for not only illegally annexing Crimea in 2014, but also funding separatist insurgencies in the Donbas and Luhansk regions of Ukraine as well as the Abkhazia and South Ossetia regions in Georgia, and Transnistria in Moldova. As during tsarist times, there is nothing benevolent about Russia’s intentions in these regions. The statehood of lands targeted for expansion are first undermined with Pan-Slavic propaganda through public school literature, state |

media, or the Russian Orthodox Church (See Part I). Once nations take notice and attempt to counter these efforts, the autocrat promotes the minorities they sueded as victims of persecution and presents Holy Russia as the savior of the very unrest they fomented, all while gaslighting the historical timeline of events leading to the conflict.

Western Accomplices

As a further misfortune to Ukrainians, there is nearly a complete lack of knowledge of Ukrainian and Eastern European history in the West. Consequently, some American journalists and even hollywood filmmakers have found themselves unwitting accomplices in cultural genocide. In 2016, director Oliverstone produced a so-called

As a further misfortune to Ukrainians, there is nearly a complete lack of knowledge of Ukrainian and Eastern European history in the West. Consequently, some American journalists and even hollywood filmmakers have found themselves unwitting accomplices in cultural genocide. In 2016, director Oliverstone produced a so-called

| documentary film on Ukrainian geopolitics titled Ukraine on Fire. Although the film targeted a skeptical niche market to American power and politics, he failed in his basic portrayal of Ukrainian history and chose instead to parrot revisionist history from the Kremlin. Instead of interviewing academics or a balance of journalists who covered the events of Maidan and Crimea in 2014, his expert witnesses were excluded to the ousted Moscow-backed president Viktor Yanukyvich, his interior staff, and Vladimir Putin. As an added insult to injury, without the slightest |

deviation from Putin’s perspective, the western filmmaker presented the same distorted history of Ukraine in a way that was both irresponsible and inexcusable to not only his audience but an entire race of people (See Part I).

Other prominent politicians, news anchors, and celebrities have either repeated Kremlin falsehoods of Ukraine’s history or its version of events following the 2014 Maidan Revolution. Even high profile figures such as Elon Musk, though has heroically supported Ukraine during their invasion with Starlink internet, has tweeted comments that demonstrate lack of attention to Putin’s campaign to undermine Ukrainian statehood from within the Donbas, Luhansk, and Crimean regions. Until knowledge of Ukrainian history becomes more mainstream, gaslighting and cultural ignorance originating from the Kremlin will continue to circulate and ultimately have the upperhand for audiences skeptical of NATO expansion or social conservatives susceptible to Putin’s belligerence in the culture wars.

Conclusion

Ukrainian culture survived Russian occupation roughly thanks to the stubborn proliferation of Ukrainian literature from the universities of Kyiv and Kharkiv, and in the southwestern part of Ukraine where it survived under a less malign occupation of Austria Hungary. However, two hundred years of Russian colonization and gaslighting cannot be sustained indefinitely. It left the Ukrainian people “russified” and suppressed their national identity. Until recent decades, Ukrainians were forbidden from openly learning their actual history and distinct cultural traditions. As a result, many Ukrainians are Russian speakers who were yet to fully decolonize themselves from their Russian yoke till the Maidan Revolution in 2014. Prior to Yanukovych’s ouster, the Kremlin influenced nearly every institution within Ukraine’s public trust: education, the Church, and corruptible political leadership. Rewriting Ukrainian history was always key to undermining Ukraine’s statehood to further prep its valuable lands for takeover. This expansionist strategy is not some clever scheme cooked up by Vladimir Putin, but rather a recycled tsarist foreign policy once used to destabilize its southern neighbors long ago. As demonstrated by the RussoTurkish Wars of the 19th century, the pattern of support for separatist movements is never about benevolence, but the gradual annexation of regions in order to inch ever closer to vital trade ports in the Black Sea: the historic geopolitical goal of every Russian autocrat. As witnessed in Native American residential schools in the United States and Canada (and with the aid of unwitting accomplices) cultural genocide inevitably leads to actual genocide.

In part 3 of this series, we will discuss the evolution of cultural genocide into real genocide of Ukrainians at the hands of the Russian government along with the denial and gaslighting that has followed the human tragedy known as Holodomor.

Other prominent politicians, news anchors, and celebrities have either repeated Kremlin falsehoods of Ukraine’s history or its version of events following the 2014 Maidan Revolution. Even high profile figures such as Elon Musk, though has heroically supported Ukraine during their invasion with Starlink internet, has tweeted comments that demonstrate lack of attention to Putin’s campaign to undermine Ukrainian statehood from within the Donbas, Luhansk, and Crimean regions. Until knowledge of Ukrainian history becomes more mainstream, gaslighting and cultural ignorance originating from the Kremlin will continue to circulate and ultimately have the upperhand for audiences skeptical of NATO expansion or social conservatives susceptible to Putin’s belligerence in the culture wars.

Conclusion

Ukrainian culture survived Russian occupation roughly thanks to the stubborn proliferation of Ukrainian literature from the universities of Kyiv and Kharkiv, and in the southwestern part of Ukraine where it survived under a less malign occupation of Austria Hungary. However, two hundred years of Russian colonization and gaslighting cannot be sustained indefinitely. It left the Ukrainian people “russified” and suppressed their national identity. Until recent decades, Ukrainians were forbidden from openly learning their actual history and distinct cultural traditions. As a result, many Ukrainians are Russian speakers who were yet to fully decolonize themselves from their Russian yoke till the Maidan Revolution in 2014. Prior to Yanukovych’s ouster, the Kremlin influenced nearly every institution within Ukraine’s public trust: education, the Church, and corruptible political leadership. Rewriting Ukrainian history was always key to undermining Ukraine’s statehood to further prep its valuable lands for takeover. This expansionist strategy is not some clever scheme cooked up by Vladimir Putin, but rather a recycled tsarist foreign policy once used to destabilize its southern neighbors long ago. As demonstrated by the RussoTurkish Wars of the 19th century, the pattern of support for separatist movements is never about benevolence, but the gradual annexation of regions in order to inch ever closer to vital trade ports in the Black Sea: the historic geopolitical goal of every Russian autocrat. As witnessed in Native American residential schools in the United States and Canada (and with the aid of unwitting accomplices) cultural genocide inevitably leads to actual genocide.

In part 3 of this series, we will discuss the evolution of cultural genocide into real genocide of Ukrainians at the hands of the Russian government along with the denial and gaslighting that has followed the human tragedy known as Holodomor.

References

Ciancia, K. C. (2011). POLAND’S WILD EAST: IMAGINED LANDSCAPES AND EVERYDAY LIFE IN THE VOLHYNIAN BORDERLANDS, 1918-1939: Doctoral Dissertation. Stanford University. https://purl.stanford.edu/sz204nw1638

Devlin, K. & Korenyuk, M. (August, 2022). Ukraine War: History is rewritten for children in occupied areas. BBC News. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-62577314

Hai-Nyzhnyk P., Chupriy L., Fihurnyi Y., Krasnodemska I., Chyrkov O. (2018). Aggression of the Russian Federation against Ukraine: ethnonational dimension and civilizational confrontation. Saarbrücken (Germany): LAP Lambert Academic Publishing. 229 p.

Korostelina, K. (2010). War of textbooks: History education in Russia and Ukraine. Communist and Post-Communist Studies, 43(2), 129–137. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.POSTCOMSTUD.2010.03.004

MacKenzie, D. & Curran, M. W. (2002). A History of Russia, the Soviet Union, and Beyond: 6th edition. Wadsworth.

Putin, V. (2021). On the historical unity of Russians and Ukrainians. Article by Vladimir Putin. Kremlin. http://en.kremlin.ru/events/president/news/66181#sel=68:55:L6w,68:122:vnx;77:33:36j,77:71:rQx;82:1:W3l,83:55:lx3

Strozewski, Z. (June, 2022). Russia Prosecutes Teacher Who Told Kids to Not 'Wish Death' on Ukrainians. Newsweek. https://www.newsweek.com/russia-prosecutes-teacher-who-told-kids-not-wish-death-ukrainians-1713558

Stone, O. (2016). Ukraine on Fire. YouTube. Retrieved November 23, 2022, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9TjeW5pPHg0.

Subtelny, O. (1988). Ukraine: A History. Toronto, pp.279-86.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed