Who Benefits From War with North Korea? | Image Credit: www.pinterest.com |

Multiple US administrations have tried and failed to get North Korea to terminate its pursuit of nuclear weapons. Under terms of the agreement reached in October 1994, North Korea agreed to freeze its capacity to make nuclear arms and allow international inspections. Arguably, this agreement gave the DPRK special status in that it did not force Pyongyang to dismantle its current facilities and the United States committed itself to ease trade restrictions and make available advanced nuclear technologies, as well as allowed it to put off for five years meeting full compliance with the provisions of the Non Proliferation Treaty (NPT).

In spite of President Clinton’s unusual and generous offer, Pyongyang did not challenge an assertion made by George W. Bush that it had a secret uranium enrichment program in his Axis of Evil speech in 2002. In December, the North Koreans ordered international inspectors out of the country and the next month withdrew from the NPT. In April 2003, North Korea acknowledged it had developed nuclear weapons. In June 2004, a meeting produced an offer by the United States to grant diplomatic recognition and support multilateral aid for North Korea if it first committed to an internationally verifiable process of dismantling its nuclear weapons. However, in July, North Korea officially rejected the offer as a sham. Days later it called upon the United Nations to dissolve the UN Command that continues to operate in South Korea. Since then, tensions have only worsened on the peninsula.

The Problem with Most Theories on North Korea

Most foreign policy experts agree that the current leader Kim Jung Un is pursuing self-preservation tactics and that China, in particular, holds the most influence over the DPRK. If this is the case, why is Kim Jong Un seemingly going out of his way to be provocative, such as shooting missiles directly over Japan? Why do the two veto welding powers of the UN Security Council, China and Russia, drag their feet when increasing sanctions and pressure on DPRK? What could possibly be China and Russia’s role in all of this? History may explain. It is possible that the answer may be more sinister than simply fear of having a unified Korea on their doorstep. What if a crisis on the Korean peninsula is exactly what they want?

How Mao and Stalin Started the Korean War (1950-53)

Thanks to interviews with many of Mao Zedong’s inner circle who have never talked before, Jung Chang’s book, Mao: The Unknown Story is full of startling revelations on the real history of the Korean War.

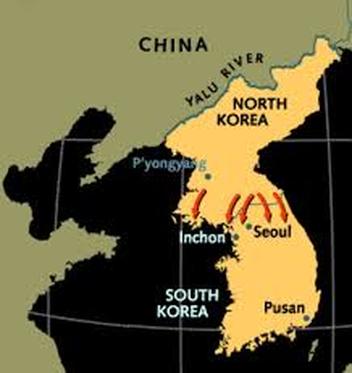

In October 1950, Mao Zedong had just consolidated power over all of China and his ambitions soon focused his resources and attention to a patch of turf that Soviet leader Joseph Stalin had decided to assign him. This was Korea. At the end of World War II, Korea, which had been occupied by Japan for nearly 30 years, was divided across the middle, along the 38th parallel, with Soviet Russia occupying the northern half and the US the South. After formal independence in 1948, the North came under a Communist dictator, Kim Il Sung, grandfather to current leader Kim Jung Un. In March 1949, as Mao’s armies were rolling towards victory over Chiang Kai-Shek, Kim went to Moscow to try to persuade Stalin to help him seize the South. Stalin said “No,” as this might involve confronting America. Kim next turned to Mao, and one month later sent his deputy defense minister to Beijing. In contrast to Stalin, Mao gave Kim a firm commitment, saying he would be glad to help Pyongyang invade the South, but Mao asked if Kim could wait until Mao had taken the whole of China. Mao in fact encouraged Pyongyang to attack the South and take on the USA. He even volunteered Chinese manpower as early as May 1949. During his visit to Russia, however, Mao changed. He became determined to fight America openly since only such a war would enable him to gouge out of Stalin what he needed to build his own world-class war machine. What Mao had in mind was a deal: Chinese troops would fight the Americans for Stalin in exchange for Soviet hardware and technology.

According to Chang & Halliday, Mao’s goal was to position China—more accurately himself—as a dominant global figure. There was one problem. The USSR under Stalin was the undisputed head of global communism and Mao was in his debt for supporting him with money and weapons to defeat Nationalist rival, Chiang Kai-Shek, in the Chinese Civil War. Mao was less subservient to Stalin than the Boss preferred, who had already grown to distrust Mao’s military build up and particular brand of Communism. A militarily powerful China would be very much a double-edged sword: a tremendous asset to the Communist camp, but also a potential threat to Stalin.

Publication of literature favorable to Mao's "Thought," such as Dawn Out of China, reached bookshelves around the globe, but ironically not in Russia. “All Asia will learn from China more than they will learn from the USSR.” Furthermore it claimed Mao’s works “highly likely influenced the later forms of government in parts of post war Europe.” These phrases alone were cause for the ban. Stalin remained totally committed to backing Mao, but he took steps to contain him and remind him who was master. Soviet media never mentioned Mao’s “Thought.” However, for now Mao needed Stalin’s help to become a major military power. Mao had begun to dream about dividing the world with Stalin. Early in Mao Zedong’s reign over the People’s Republic of China, he had one specific goal in mind: he needed to persuade Stalin to aid his nation in developing an atom bomb.

Meanwhile, Kim Il Sun was telling Stalin that Mao was eager to give him military support, and that if Stalin would still not endorse an invasion, he (Kim) would go to Mao direct and place himself under Mao.

A war in Korea fought by Chinese and Koreans would give the Soviet Union immeasurable advantages: it could field-test both its own new equipment, such as its MiG jets against America’s technology, as well as attaining some of this technology, along with vital intelligence on America. Furthermore, he could test how far America would go in a war with the Communist camp. But for Stalin, the greatest appeal of a war in Korea was that the Chinese, with their immense numbers, which Mao was eager to use, might be able to defeat, and in any case tie down, so many American troops that the balance of power might tilt in Stalin’s favor and allow him to turn his schemes into reality. These schemes included occupying various European countries, among them Germany, Italy and Spain.

On July 1, 1950, within a week of the North invading the South, and long before Chinese troops had gone in, Mao Zedong had told the Russian ambassador: “Now we must energetically build up our aviation and fleet so as to deal a knock out blow…to the armed forces of the USA.”

Russia’s Commonly Misunderstood Boycott

Korean War history books frequently point to the success of the UN’s resolution to send troops to intervene in the Korean War as the result of Russia (which holds veto power) boycotting the Security Council ostensibly over Taiwan continuing to occupy China’s seat. Stalin’s ambassador to the UN, Yakov Malik, had been boycotting proceedings since January. However, everyone expected Malik, who remained in New York, to return to the chamber and veto the resolution, but he stayed away. The fact is Malik had requested permission to return to the Security Council, but Stalin personally rang him up and told him to stay out. Soviet failure to exercise its veto has perplexed observers since, as it seemed to throw away a golden opportunity to block the UN’s military involvement in Korea. But if Stalin decided not to use his veto, the likely explanation is that he did not want to keep Western forces out. He wanted them in, where Mao’s utter weight of numbers could grind them up. Kim wanted Chinese troops kept out until they were absolutely necessary. Stalin, too, wanted them in only when America committed large numbers of troops for the Chinese to “consume.”

Truman reacted fast to the invasion. Within two days, on the 27th, he announced that he was sending troops into Korea, as well as reversing the policy of “non-intervention” towards Taiwan. It was because of this new US pledge that neither Mao nor his successors were ever able to take Taiwan. The US had complete air supremacy, and artillery superiority of about 40:1. But Mao wagered that America would not expand the war to China. Chinese cities and industrial bases could be protected from US bombing by the Russian air force. Mao knew that America just would not be able to compete in sacrificing men. He was ready to risk all because having Chinese troops fighting the USA was the only chance he had to claw out of Stalin what he needed to make China a world-class military power. Mao prepared the ground for going into Korea by pretending to give America “fair warning.” For this purpose he staged a charade, waking the Indian ambassador in the early hours of October 3rd to tell him “ we will intervene” if American troops crossed the 38th parallel. Mao wanted his “warning” to be ignored: thus he could go into Korea claiming he was acting out of self-defense.

Mao Prolongs the War

Mao needed the war. It was out of global ambitions and that China not only got involved in the Korean War, but also sustained it to put pressure on Stalin. According the Chang & Halliday, Kim wanted to stop north of the 38th parallel, the original boundary between North and South Korea, but Mao refused. Mao told his advisors to expect the war to be a long one: “Don’t try to win a quick victory.” In time, Mao’s plan partially worked. On February 19, 1951, Moscow endorsed a preliminary agreement to start building factories in China to repair and service planes. By the end of the war, China, a very poor country, had the third largest air force in the world, 3,000 planes, including advanced MiGs. Mao upped the ante by asking for the blueprints for all the weapons the Soviets were using in Korea. Although Stalin wanted China to do his fighting for him, and was happy to sell Mao the weapons for the sixty divisions, he had no intension of endowing Mao with a full-blown arms industry. The Russians reluctantly agreed to transfer the technology for producing seven kinds of small arms including machine-guns, but declined to divulge more.

Kim saw that he might end up ruling over a wasteland and possibly a shrunken one at that. He wanted an end to the war. On June 3, 1951 he went to China in secret to discuss opening negotiations with the US. As Mao was nowhere near his goal, the last thing he was interested in was stopping the war. Instead he ordered Chinese troops to draw UN forces deeper into North Korea “ the farther north the better,” he said, provided it was not too near the Chinese border. Mao had hijacked the war, and was using Korea regardless of Kim’s interests.

The UN forces held over 20,000 Chinese, predominantly former Nationalist troops, most of whom did not wish to return to Communist China. Recalling what happened to prisoners returned to Stalin at the end of World War II, many to their deaths, America rejected involuntary repatriation, for both humanitarian and political reasons. But Mao’s line was: “Not a single one is to get away!” This protracted the war for a year and a half. Mao could care less about the POWs. He needed a dispute to drag out the war so that he could extract more from Stalin.

On February 2, 1953 the new US president, Eisenhower, suggested in his State of the Union address that he might use the atomic bomb on China. This threat was actually music to Mao’s ears, as he now had an excuse to ask Stalin for what he wanted most: nuclear weapons. Stalin did not want to give Mao the bomb, but when Stalin died, it was Mao’s moment of liberation. However, Stalin’s successors were eager to lessen tension with the West, and made it clear a large number of arms enterprises, which Stalin had been delaying, would be rewarded to Mao if he cooperated in ending the Korean War. Unlike Stalin, who saw Mao as his personal rival, the new Soviet leaders took the attitude that a militarily powerful China was good for the Communist camp. An armistice was finally signed on July 27, 1953.

How Russia and China Support North Korea Today

Today, North Korea’s regime under Kim Il Sung’s grandson, Kim Jung Un, has developed nuclear weapons and advanced missile technology surprisingly fast within the last few years. This has only been possible with the help of foreign suppliers, meaning countries from the former Soviet Union.

According to a New York Times report published in September, 2017, North Korea’s surprising progress in missile technology may be linked to Yuzhmash, the former Soviet rocket engine manufacturer based in Eastern Ukraine. It is difficult to prove whether the RD-250 engines used in the rockets were manufactured by Yuzhmash, but production managers say these engines were meant for Russia, where they were "produced in low quantities." In his IISS study, Michael Elleman wrote that "hundreds, if not more" RD-250 engines have remained in Russia, as well as in Ukraine, adding it is also possible that Moscow is Pyongyang's supplier. However, the Times reporter only provided “clues” and speculation without any hard evidence.

When South Korea and Japan probed Russia to halt oil deliveries to North Korea before the vote at the Security Council, President Vladimir Putin downplayed their concerns and claimed that Russia was only exporting about "40,000 tons of oil and petroleum products per quarter." Furthermore, Putin said that large Russian companies were not affiliated in trade with the DPRK. Conversely, even at those small amounts the country has almost doubled its fossil fuel exports to North Korea in the first half of 2017 according to Russian media reports based upon records from Russia's tax authority.

According to a former North Korean official who defected to the South, the reality of the actual amount of oil being exported to the DPRK from Russia is likely significantly higher than official records report. He claimed that Russia was actually delivering some 200,000 to 300,000 tons of petroleum to Pyongyang each year. Artyom Lukin of the Far Eastern Federal University in Vladivostok, Russia, agrees with that estimate. "At current prices that amount of oil would add up to about $300 million (252 million euros) a year," said the foreign policy expert while speaking with Deutche Welle. If those figure were correct then it would be more than three times greater than official figures suggest. The reason: “trading takes place in gray zones away from official markets, and the resource is often routed through China.”

North Korea gets the majority of Russia's oil deliveries through middlemen and therefore do not appear on official customs documents, says Lukin. "For instance, a gasoline delivery will be declared to be destined for China or Singapore, but then it shows up in North Korea. The reason for that is that sanctions against trading with North Korea make bank transfers "practically impossible." As a result, Russian suppliers use well-connected "Chinese middlemen." The Washington Post also reported on Russia's indirect sales of oil to Pyongyang. Moreover, the newspaper based its findings on increased tanker traffic between Vladivostok and North Korea in the spring of 2017. If confirmed, such actions would be a violation of UN sanctions against Pyongyang.

Moscow has been firmly reinforcing its relationship with North Korea over the last three years as part of its so-called "eastward pivot," which has in turn been exacerbated by Russia's tensions with the West over its annexation of Crimea. In 2014 Russia offered debt relief to Pyongyang, taking a loss of around $10 billion on loans remaining from the days of the former USSR. That same year the two nations agreed upon the ruble as the currency for all future transactions. In 2015 the Russian Chamber of Commerce initiated an economic council for relations with DPRK. Russia's then minister for Far East development declared that Putin intended to intensify its trade volume with North Korea tenfold – to roughly $1 billion – by 2020. But so far nothing has come of that. Trade plummeted from about $113 million in 2013 to roughly $77 million last year, conversely in 2017 – thanks mainly to oil exports – customs officials have registered an increase.

Conclusion

It is a little known fact that Russia and China have historically conspired to use North Korea as a pawn to offset US balance in the past. The 1950-53 Korean War was meant to increase Western Europe’s vulnerability to Stalin’s red army, while Mao Zedong used the Korean War to place pressure on the Russians finally aid China with the latest military technology. However, this plan was cut short due to Stalin’s sudden death in March 1953. Today, Russia’s annexation of Crimea in 2014 has been interpreted as hostile aggression by many in the West who fear the former KGB agent, Vladimir Putin, is plotting a return to the old Cold War playbook in aggrandizing Russia’s global position. Although reports of Russian support of Kim Jong Un’s ballistic missile program lack evidence, it is clear that Russia has increased relations and trade with the rogue DPRK regime in recent years, while working closely with China in their approach to the increased tensions on the peninsula. In a world where the United States has a precarious national debt of over 20 trillion dollars, yet nonetheless manages to hinder Russian expansion in the west and Chinese expansion in the South China Sea; it is not far-fetched to believe having the United States involved in another costly war on the Korean peninsula would serve to benefit these two global rivals.

References

Broad, W. J., & Sanger, D. E. (2017, August 14). North Korea’s Missile Success Is Linked to Ukrainian Plant, Investigators Say. The New York Times. Retrieved October 1, 2017, from https://www.nytimes.com/2017/08/14/world/asia/north-korea-missiles-ukraine-factory.html

Calamur, K. (2017, September 6). How Did North Korea’s Missile and Nuclear Tech Get So Good So Fast? The Atlantic. Retrieved Autumn, 2017, from https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2017/09/north-korea-tech/538959/

Chang, J. and Halliday, J. (2005). Mao: The Unknown Story. Anchor Books: New York.

Goncharenk, R. (2017, September 14). How North Korea Survives on an Oil Drip from Russia. Deutche Welle. Retrieved from http://www.dw.com/en/how-north-korea-survives-on-an-oil-drip-from-russia/a-40498208

Hastedt, G. P. (2017). American Foreign Policy: Past, Present, and Future 11th Edition. Rowman & Littlefield: James Madison University

Warrick, J. (2017, September 11). How Russia Quietly Undercuts Sanction Intended to Stop North Korea’s Nuclear Program. Washington Post. Retrieved October 10, 2017, from https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/national-security/how-russia-quietly-undercuts-sanctions-intended-to-stop-north-koreas-nuclear-program/2017/09/11/f963867e-93e4-11e7-8754-d478688d23b4_story.html?utm_term=.aa1fd1afa59e

In spite of President Clinton’s unusual and generous offer, Pyongyang did not challenge an assertion made by George W. Bush that it had a secret uranium enrichment program in his Axis of Evil speech in 2002. In December, the North Koreans ordered international inspectors out of the country and the next month withdrew from the NPT. In April 2003, North Korea acknowledged it had developed nuclear weapons. In June 2004, a meeting produced an offer by the United States to grant diplomatic recognition and support multilateral aid for North Korea if it first committed to an internationally verifiable process of dismantling its nuclear weapons. However, in July, North Korea officially rejected the offer as a sham. Days later it called upon the United Nations to dissolve the UN Command that continues to operate in South Korea. Since then, tensions have only worsened on the peninsula.

The Problem with Most Theories on North Korea

Most foreign policy experts agree that the current leader Kim Jung Un is pursuing self-preservation tactics and that China, in particular, holds the most influence over the DPRK. If this is the case, why is Kim Jong Un seemingly going out of his way to be provocative, such as shooting missiles directly over Japan? Why do the two veto welding powers of the UN Security Council, China and Russia, drag their feet when increasing sanctions and pressure on DPRK? What could possibly be China and Russia’s role in all of this? History may explain. It is possible that the answer may be more sinister than simply fear of having a unified Korea on their doorstep. What if a crisis on the Korean peninsula is exactly what they want?

How Mao and Stalin Started the Korean War (1950-53)

Thanks to interviews with many of Mao Zedong’s inner circle who have never talked before, Jung Chang’s book, Mao: The Unknown Story is full of startling revelations on the real history of the Korean War.

In October 1950, Mao Zedong had just consolidated power over all of China and his ambitions soon focused his resources and attention to a patch of turf that Soviet leader Joseph Stalin had decided to assign him. This was Korea. At the end of World War II, Korea, which had been occupied by Japan for nearly 30 years, was divided across the middle, along the 38th parallel, with Soviet Russia occupying the northern half and the US the South. After formal independence in 1948, the North came under a Communist dictator, Kim Il Sung, grandfather to current leader Kim Jung Un. In March 1949, as Mao’s armies were rolling towards victory over Chiang Kai-Shek, Kim went to Moscow to try to persuade Stalin to help him seize the South. Stalin said “No,” as this might involve confronting America. Kim next turned to Mao, and one month later sent his deputy defense minister to Beijing. In contrast to Stalin, Mao gave Kim a firm commitment, saying he would be glad to help Pyongyang invade the South, but Mao asked if Kim could wait until Mao had taken the whole of China. Mao in fact encouraged Pyongyang to attack the South and take on the USA. He even volunteered Chinese manpower as early as May 1949. During his visit to Russia, however, Mao changed. He became determined to fight America openly since only such a war would enable him to gouge out of Stalin what he needed to build his own world-class war machine. What Mao had in mind was a deal: Chinese troops would fight the Americans for Stalin in exchange for Soviet hardware and technology.

According to Chang & Halliday, Mao’s goal was to position China—more accurately himself—as a dominant global figure. There was one problem. The USSR under Stalin was the undisputed head of global communism and Mao was in his debt for supporting him with money and weapons to defeat Nationalist rival, Chiang Kai-Shek, in the Chinese Civil War. Mao was less subservient to Stalin than the Boss preferred, who had already grown to distrust Mao’s military build up and particular brand of Communism. A militarily powerful China would be very much a double-edged sword: a tremendous asset to the Communist camp, but also a potential threat to Stalin.

Publication of literature favorable to Mao's "Thought," such as Dawn Out of China, reached bookshelves around the globe, but ironically not in Russia. “All Asia will learn from China more than they will learn from the USSR.” Furthermore it claimed Mao’s works “highly likely influenced the later forms of government in parts of post war Europe.” These phrases alone were cause for the ban. Stalin remained totally committed to backing Mao, but he took steps to contain him and remind him who was master. Soviet media never mentioned Mao’s “Thought.” However, for now Mao needed Stalin’s help to become a major military power. Mao had begun to dream about dividing the world with Stalin. Early in Mao Zedong’s reign over the People’s Republic of China, he had one specific goal in mind: he needed to persuade Stalin to aid his nation in developing an atom bomb.

Meanwhile, Kim Il Sun was telling Stalin that Mao was eager to give him military support, and that if Stalin would still not endorse an invasion, he (Kim) would go to Mao direct and place himself under Mao.

A war in Korea fought by Chinese and Koreans would give the Soviet Union immeasurable advantages: it could field-test both its own new equipment, such as its MiG jets against America’s technology, as well as attaining some of this technology, along with vital intelligence on America. Furthermore, he could test how far America would go in a war with the Communist camp. But for Stalin, the greatest appeal of a war in Korea was that the Chinese, with their immense numbers, which Mao was eager to use, might be able to defeat, and in any case tie down, so many American troops that the balance of power might tilt in Stalin’s favor and allow him to turn his schemes into reality. These schemes included occupying various European countries, among them Germany, Italy and Spain.

On July 1, 1950, within a week of the North invading the South, and long before Chinese troops had gone in, Mao Zedong had told the Russian ambassador: “Now we must energetically build up our aviation and fleet so as to deal a knock out blow…to the armed forces of the USA.”

Russia’s Commonly Misunderstood Boycott

Korean War history books frequently point to the success of the UN’s resolution to send troops to intervene in the Korean War as the result of Russia (which holds veto power) boycotting the Security Council ostensibly over Taiwan continuing to occupy China’s seat. Stalin’s ambassador to the UN, Yakov Malik, had been boycotting proceedings since January. However, everyone expected Malik, who remained in New York, to return to the chamber and veto the resolution, but he stayed away. The fact is Malik had requested permission to return to the Security Council, but Stalin personally rang him up and told him to stay out. Soviet failure to exercise its veto has perplexed observers since, as it seemed to throw away a golden opportunity to block the UN’s military involvement in Korea. But if Stalin decided not to use his veto, the likely explanation is that he did not want to keep Western forces out. He wanted them in, where Mao’s utter weight of numbers could grind them up. Kim wanted Chinese troops kept out until they were absolutely necessary. Stalin, too, wanted them in only when America committed large numbers of troops for the Chinese to “consume.”

Truman reacted fast to the invasion. Within two days, on the 27th, he announced that he was sending troops into Korea, as well as reversing the policy of “non-intervention” towards Taiwan. It was because of this new US pledge that neither Mao nor his successors were ever able to take Taiwan. The US had complete air supremacy, and artillery superiority of about 40:1. But Mao wagered that America would not expand the war to China. Chinese cities and industrial bases could be protected from US bombing by the Russian air force. Mao knew that America just would not be able to compete in sacrificing men. He was ready to risk all because having Chinese troops fighting the USA was the only chance he had to claw out of Stalin what he needed to make China a world-class military power. Mao prepared the ground for going into Korea by pretending to give America “fair warning.” For this purpose he staged a charade, waking the Indian ambassador in the early hours of October 3rd to tell him “ we will intervene” if American troops crossed the 38th parallel. Mao wanted his “warning” to be ignored: thus he could go into Korea claiming he was acting out of self-defense.

Mao Prolongs the War

Mao needed the war. It was out of global ambitions and that China not only got involved in the Korean War, but also sustained it to put pressure on Stalin. According the Chang & Halliday, Kim wanted to stop north of the 38th parallel, the original boundary between North and South Korea, but Mao refused. Mao told his advisors to expect the war to be a long one: “Don’t try to win a quick victory.” In time, Mao’s plan partially worked. On February 19, 1951, Moscow endorsed a preliminary agreement to start building factories in China to repair and service planes. By the end of the war, China, a very poor country, had the third largest air force in the world, 3,000 planes, including advanced MiGs. Mao upped the ante by asking for the blueprints for all the weapons the Soviets were using in Korea. Although Stalin wanted China to do his fighting for him, and was happy to sell Mao the weapons for the sixty divisions, he had no intension of endowing Mao with a full-blown arms industry. The Russians reluctantly agreed to transfer the technology for producing seven kinds of small arms including machine-guns, but declined to divulge more.

Kim saw that he might end up ruling over a wasteland and possibly a shrunken one at that. He wanted an end to the war. On June 3, 1951 he went to China in secret to discuss opening negotiations with the US. As Mao was nowhere near his goal, the last thing he was interested in was stopping the war. Instead he ordered Chinese troops to draw UN forces deeper into North Korea “ the farther north the better,” he said, provided it was not too near the Chinese border. Mao had hijacked the war, and was using Korea regardless of Kim’s interests.

The UN forces held over 20,000 Chinese, predominantly former Nationalist troops, most of whom did not wish to return to Communist China. Recalling what happened to prisoners returned to Stalin at the end of World War II, many to their deaths, America rejected involuntary repatriation, for both humanitarian and political reasons. But Mao’s line was: “Not a single one is to get away!” This protracted the war for a year and a half. Mao could care less about the POWs. He needed a dispute to drag out the war so that he could extract more from Stalin.

On February 2, 1953 the new US president, Eisenhower, suggested in his State of the Union address that he might use the atomic bomb on China. This threat was actually music to Mao’s ears, as he now had an excuse to ask Stalin for what he wanted most: nuclear weapons. Stalin did not want to give Mao the bomb, but when Stalin died, it was Mao’s moment of liberation. However, Stalin’s successors were eager to lessen tension with the West, and made it clear a large number of arms enterprises, which Stalin had been delaying, would be rewarded to Mao if he cooperated in ending the Korean War. Unlike Stalin, who saw Mao as his personal rival, the new Soviet leaders took the attitude that a militarily powerful China was good for the Communist camp. An armistice was finally signed on July 27, 1953.

How Russia and China Support North Korea Today

Today, North Korea’s regime under Kim Il Sung’s grandson, Kim Jung Un, has developed nuclear weapons and advanced missile technology surprisingly fast within the last few years. This has only been possible with the help of foreign suppliers, meaning countries from the former Soviet Union.

According to a New York Times report published in September, 2017, North Korea’s surprising progress in missile technology may be linked to Yuzhmash, the former Soviet rocket engine manufacturer based in Eastern Ukraine. It is difficult to prove whether the RD-250 engines used in the rockets were manufactured by Yuzhmash, but production managers say these engines were meant for Russia, where they were "produced in low quantities." In his IISS study, Michael Elleman wrote that "hundreds, if not more" RD-250 engines have remained in Russia, as well as in Ukraine, adding it is also possible that Moscow is Pyongyang's supplier. However, the Times reporter only provided “clues” and speculation without any hard evidence.

When South Korea and Japan probed Russia to halt oil deliveries to North Korea before the vote at the Security Council, President Vladimir Putin downplayed their concerns and claimed that Russia was only exporting about "40,000 tons of oil and petroleum products per quarter." Furthermore, Putin said that large Russian companies were not affiliated in trade with the DPRK. Conversely, even at those small amounts the country has almost doubled its fossil fuel exports to North Korea in the first half of 2017 according to Russian media reports based upon records from Russia's tax authority.

According to a former North Korean official who defected to the South, the reality of the actual amount of oil being exported to the DPRK from Russia is likely significantly higher than official records report. He claimed that Russia was actually delivering some 200,000 to 300,000 tons of petroleum to Pyongyang each year. Artyom Lukin of the Far Eastern Federal University in Vladivostok, Russia, agrees with that estimate. "At current prices that amount of oil would add up to about $300 million (252 million euros) a year," said the foreign policy expert while speaking with Deutche Welle. If those figure were correct then it would be more than three times greater than official figures suggest. The reason: “trading takes place in gray zones away from official markets, and the resource is often routed through China.”

North Korea gets the majority of Russia's oil deliveries through middlemen and therefore do not appear on official customs documents, says Lukin. "For instance, a gasoline delivery will be declared to be destined for China or Singapore, but then it shows up in North Korea. The reason for that is that sanctions against trading with North Korea make bank transfers "practically impossible." As a result, Russian suppliers use well-connected "Chinese middlemen." The Washington Post also reported on Russia's indirect sales of oil to Pyongyang. Moreover, the newspaper based its findings on increased tanker traffic between Vladivostok and North Korea in the spring of 2017. If confirmed, such actions would be a violation of UN sanctions against Pyongyang.

Moscow has been firmly reinforcing its relationship with North Korea over the last three years as part of its so-called "eastward pivot," which has in turn been exacerbated by Russia's tensions with the West over its annexation of Crimea. In 2014 Russia offered debt relief to Pyongyang, taking a loss of around $10 billion on loans remaining from the days of the former USSR. That same year the two nations agreed upon the ruble as the currency for all future transactions. In 2015 the Russian Chamber of Commerce initiated an economic council for relations with DPRK. Russia's then minister for Far East development declared that Putin intended to intensify its trade volume with North Korea tenfold – to roughly $1 billion – by 2020. But so far nothing has come of that. Trade plummeted from about $113 million in 2013 to roughly $77 million last year, conversely in 2017 – thanks mainly to oil exports – customs officials have registered an increase.

Conclusion

It is a little known fact that Russia and China have historically conspired to use North Korea as a pawn to offset US balance in the past. The 1950-53 Korean War was meant to increase Western Europe’s vulnerability to Stalin’s red army, while Mao Zedong used the Korean War to place pressure on the Russians finally aid China with the latest military technology. However, this plan was cut short due to Stalin’s sudden death in March 1953. Today, Russia’s annexation of Crimea in 2014 has been interpreted as hostile aggression by many in the West who fear the former KGB agent, Vladimir Putin, is plotting a return to the old Cold War playbook in aggrandizing Russia’s global position. Although reports of Russian support of Kim Jong Un’s ballistic missile program lack evidence, it is clear that Russia has increased relations and trade with the rogue DPRK regime in recent years, while working closely with China in their approach to the increased tensions on the peninsula. In a world where the United States has a precarious national debt of over 20 trillion dollars, yet nonetheless manages to hinder Russian expansion in the west and Chinese expansion in the South China Sea; it is not far-fetched to believe having the United States involved in another costly war on the Korean peninsula would serve to benefit these two global rivals.

References

Broad, W. J., & Sanger, D. E. (2017, August 14). North Korea’s Missile Success Is Linked to Ukrainian Plant, Investigators Say. The New York Times. Retrieved October 1, 2017, from https://www.nytimes.com/2017/08/14/world/asia/north-korea-missiles-ukraine-factory.html

Calamur, K. (2017, September 6). How Did North Korea’s Missile and Nuclear Tech Get So Good So Fast? The Atlantic. Retrieved Autumn, 2017, from https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2017/09/north-korea-tech/538959/

Chang, J. and Halliday, J. (2005). Mao: The Unknown Story. Anchor Books: New York.

Goncharenk, R. (2017, September 14). How North Korea Survives on an Oil Drip from Russia. Deutche Welle. Retrieved from http://www.dw.com/en/how-north-korea-survives-on-an-oil-drip-from-russia/a-40498208

Hastedt, G. P. (2017). American Foreign Policy: Past, Present, and Future 11th Edition. Rowman & Littlefield: James Madison University

Warrick, J. (2017, September 11). How Russia Quietly Undercuts Sanction Intended to Stop North Korea’s Nuclear Program. Washington Post. Retrieved October 10, 2017, from https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/national-security/how-russia-quietly-undercuts-sanctions-intended-to-stop-north-koreas-nuclear-program/2017/09/11/f963867e-93e4-11e7-8754-d478688d23b4_story.html?utm_term=.aa1fd1afa59e

RSS Feed

RSS Feed