| By Timothy Holtgrefe July 2023 For several years prior to Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, President Vladimir Putin had devoted much of his time and effort to promoting false narratives and a revisionist history of Ukraine as early as 2005. However, the rhetorical gaslighting and denial of Ukraine’s rich cultural heritage is actually nothing new. In fact for Russian autocrats it is an historical continuity going back several hundred years in an effort to subjugate a race of people. |

What is surprising is not that the Russian Empire ‘russified’ their ethnic minorities, as all colonizers have performed similar practices, but that so many of these false narratives continue to persist into today’s political discourse regarding the current war in Ukraine; even in the West. This is part 4 of an HQ exclusive series to investigate Russia’s relentless attack on history. In this episode, we will explore Stalin’s genocide of Ukrainians, known as Holodomor (1932-33) and Russia’s continual denial and gaslighting of this horrendous crime.

What is Holodomor?

It was one of the greatest crimes of the 20th century. Perhaps the greatest crime of the 21st century is how few even acknowledge it. Between 1931-34, approximately 5 to 12 million citizens of the Soviet Union perished from a man-made famine resulting from Joseph Stalin’s catastrophic policies of forced collectivization of farmlands. Since the fall of the Soviet Union, there has been a wealth of literature documenting this event as Soviet archives and eye-witness accounts became unrestricted for researchers to access. Historians and textbooks, both Russian and international, universally recognize the millions of deaths from hunger and that Stalin’s policies were the catalyst.

However, for Ukrainians the period of 1932-34 in particular is remembered as Holodomor or “extermination through hunger.” Though initially as part of the wider famine throughout the U.S.S.R., Stalin exacerbated the crisis as a campaign to deliberately target Ukrainians to destroy their cultural identity and exterminate them as a race. Although there is a wealth of evidence today documenting these goals, still the Russian Federation vehemently denies this and even some western countries are still hesitant to formally recognize Holodomor as a genocide.

On November 23, 2017, two days prior to Holodomor Rememberance Day, Russian Foreign Ministry Spokesperson Maria Zakharova told the international press that the Ukrainian government’s use of the phrase “the genocide of Ukrainians” is “politically charged” and “contradicts historical facts” (Johnson, 2017). Similar denials have been repeated by Putin and Russian state media.

Although the Kremlin’s denial of Holodomor may not come as a surprise, why have so many European nations waited until Russia’s unprovoked invasion in 2022 to formally call Holodomor a genocide? Why has Russian gaslighting towards Ukraine been so effective to the western historical memory?

Why Holodomor Fits the Definition of ‘Genocide’

In short, the initial Soviet famine of 1931 was a result of Stalin’s reckless push for collective farming. However, this famine would later classify as genocide towards Ukrainians due to the following facts: 1) it had all the familiar scapegoating and hatred that preludes genocides, 2) the disproportionate enforcement of ‘blacklists’ on Ukrainian villages—confiscating all food stuffs, 3) the disproportionate extraction of grain from Soviet Ukraine that was exported abroad, 4) Stalin’s knowledge of the outcome his policies were having, and 5) the colonization of Ukraine by ethnic Russians in the aftermath.

As shown in Part 3, whether Lenin’s famine (1918-22) was deliberate or not, the Soviets noticed it was effective in destroying peasant rebellions throughout the USSR, and knew they were especially unpopular in Ukraine’s countryside. Their rejection of everything that looked or sounded “Ukrainian” kept nationalist, anti-Bolshevik anger alive. Switching tactics, in 1923 Moscow launched a new “indigenization” policy (korenizatsiia) designed to appeal to the Soviet federal state’s non-Russian minorities. It gave them official status and even priority to their national languages, promoted their national culture, and offered what was in effect an affirmative-action policy. In Ukraine it was known as “Ukrainization.” (Applebaum, 2017, p.81). The goal of this policy was to make Soviet power seem less foreign to Ukrainians, and thus reduce their demands for sovereignty. However, Stalin, as would Putin 80 years later, blamed Lenin’s Ukrainization strategy for emboldening Ukrainian nationalism and instead chose famine as a political weapon once again.

It was one of the greatest crimes of the 20th century. Perhaps the greatest crime of the 21st century is how few even acknowledge it. Between 1931-34, approximately 5 to 12 million citizens of the Soviet Union perished from a man-made famine resulting from Joseph Stalin’s catastrophic policies of forced collectivization of farmlands. Since the fall of the Soviet Union, there has been a wealth of literature documenting this event as Soviet archives and eye-witness accounts became unrestricted for researchers to access. Historians and textbooks, both Russian and international, universally recognize the millions of deaths from hunger and that Stalin’s policies were the catalyst.

However, for Ukrainians the period of 1932-34 in particular is remembered as Holodomor or “extermination through hunger.” Though initially as part of the wider famine throughout the U.S.S.R., Stalin exacerbated the crisis as a campaign to deliberately target Ukrainians to destroy their cultural identity and exterminate them as a race. Although there is a wealth of evidence today documenting these goals, still the Russian Federation vehemently denies this and even some western countries are still hesitant to formally recognize Holodomor as a genocide.

On November 23, 2017, two days prior to Holodomor Rememberance Day, Russian Foreign Ministry Spokesperson Maria Zakharova told the international press that the Ukrainian government’s use of the phrase “the genocide of Ukrainians” is “politically charged” and “contradicts historical facts” (Johnson, 2017). Similar denials have been repeated by Putin and Russian state media.

Although the Kremlin’s denial of Holodomor may not come as a surprise, why have so many European nations waited until Russia’s unprovoked invasion in 2022 to formally call Holodomor a genocide? Why has Russian gaslighting towards Ukraine been so effective to the western historical memory?

Why Holodomor Fits the Definition of ‘Genocide’

In short, the initial Soviet famine of 1931 was a result of Stalin’s reckless push for collective farming. However, this famine would later classify as genocide towards Ukrainians due to the following facts: 1) it had all the familiar scapegoating and hatred that preludes genocides, 2) the disproportionate enforcement of ‘blacklists’ on Ukrainian villages—confiscating all food stuffs, 3) the disproportionate extraction of grain from Soviet Ukraine that was exported abroad, 4) Stalin’s knowledge of the outcome his policies were having, and 5) the colonization of Ukraine by ethnic Russians in the aftermath.

As shown in Part 3, whether Lenin’s famine (1918-22) was deliberate or not, the Soviets noticed it was effective in destroying peasant rebellions throughout the USSR, and knew they were especially unpopular in Ukraine’s countryside. Their rejection of everything that looked or sounded “Ukrainian” kept nationalist, anti-Bolshevik anger alive. Switching tactics, in 1923 Moscow launched a new “indigenization” policy (korenizatsiia) designed to appeal to the Soviet federal state’s non-Russian minorities. It gave them official status and even priority to their national languages, promoted their national culture, and offered what was in effect an affirmative-action policy. In Ukraine it was known as “Ukrainization.” (Applebaum, 2017, p.81). The goal of this policy was to make Soviet power seem less foreign to Ukrainians, and thus reduce their demands for sovereignty. However, Stalin, as would Putin 80 years later, blamed Lenin’s Ukrainization strategy for emboldening Ukrainian nationalism and instead chose famine as a political weapon once again.

1. Scapegoating and Hatred of Ukrainians

Concluding that Ukrainization had failed to Sovietize Ukraine, Stalin began a vicious propaganda campaign against them. Ukraine’s nationalists were enemies and traitors, a “fifth column” that had infiltrated the Soviet system on behalf of “foreign powers,” and were the cause of all Soviet troubles. (Applebaum, 2017, p.113). Since, someone had to be blamed for the slow Soviet economic growth (and it would not be Stalin), Ukrainian peasants were a convenient scapegoat. Again and again Soviet media had declared that food shortages in the cities were not caused by collectivization, but rather greedy peasants who were hoarding their produce for themselves, called ‘kulaks.’ On his orders, the Joint State Political Directorate (OGPU) “discovered” various conspiracies by workers who allegedly were aiming to destroy the coal industry, in league with foreign powers (p.115). The result was

Concluding that Ukrainization had failed to Sovietize Ukraine, Stalin began a vicious propaganda campaign against them. Ukraine’s nationalists were enemies and traitors, a “fifth column” that had infiltrated the Soviet system on behalf of “foreign powers,” and were the cause of all Soviet troubles. (Applebaum, 2017, p.113). Since, someone had to be blamed for the slow Soviet economic growth (and it would not be Stalin), Ukrainian peasants were a convenient scapegoat. Again and again Soviet media had declared that food shortages in the cities were not caused by collectivization, but rather greedy peasants who were hoarding their produce for themselves, called ‘kulaks.’ On his orders, the Joint State Political Directorate (OGPU) “discovered” various conspiracies by workers who allegedly were aiming to destroy the coal industry, in league with foreign powers (p.115). The result was

| elaborate show trials. One of which featured members of the Liberation of Ukraine, the Spilka Vyznolennia Ukrainy or SVU, an organization which seems to have been entirely fictional. Through forced confessions and naming collaborators under interrogative torture, the goal was clear: to arrest anyone who might secretly harbor belief in Ukrainian independence, and the destruction of that |

belief once and for all (Kotkin, 2015, p.703-4). Teachers and students were particular targets. Directors of universities and libraries were arrested for catering to the “bourgeois nationalists” and for allegedly recruiting ‘kulak’ children. No evidence was produced against these individuals, even during the show trials. Public confessions were all that were needed to fuel the propaganda and paranoia of foreign counterrevolutionary conspiracies sabotaging the Soviet economy. Officers who “discovered” nationalist conspiracies in Ukraine received promotions (Shkandrij & Bertelsen, 2013). From 1927 onward, Ukrainians once again lived in fear of speaking their native language as it often raised suspicion of being any host of labels created by the public disinformation campaign: kulak, bourgeois nationalist, or foreign agent of Poland. Although the grain shortage and Ukrainian nationalist aspirations were separate issues, Stalin made them interlinked. In his 1925 speech, he declared that “the peasantry constitutes the main army of the national movement, that there is no

| powerful national movement without the peasant army.” (Stalin, 1925). In a certain sense, Stalin’s fears were correct. Peasants would surely revolt against confiscation of their property. Reports of resistance flooded in from Siberia, the North Caucasus, and Ukraine. Later in 1932, inspired and terrified by the propaganda machine, Soviet collectivization brigades resorted to outright intimidation and |

torture in order to enforce grain requisitions that they knew would starve millions. One of the people gripped with revolutionary fervor was Lev Kopelev:

With the rest of my generation, I firmly believed that the ends justified the means. Our great goal was the universal triumph of Communism, and for the sake of the goals everything was permissible—to lie, to steal, to destroy hundreds of thousands and even millions of people…everyone who stood in the way. (cited by Applebaum, 2017, p.138).

The mass arrests and deportation of Ukrainian peasants to gulags were the beginnings of the “dekulakization” process. But who was a kulak? In practice, it was anyone who withheld grain to feed themselves or their family or refused to join the collective farm.

Today, Stalinist linkage of Ukrainian nationalism and foreign interference still persists today. Following the old KGB playbook, Putin links any separation of Ukraine and Russia as artificial and part of a foreign conspiracy to attack the Russian Federation. Although Russia was the only foreign entity actively meddling in Ukraine’s internal affairs (see Part 2), Putin and his state-owned media insist that Ukraine’s 2004 and 2014 revolutions to rid themselves of Russian influence were in fact NATO/American led coups. A recorded telephone call between US assistant secretary Victoria Nuland and Ambassador Geoffrey Pyatt is frequently cited as ‘proof’ of western meddling. However, the dialogue never mentions actions or plans, only speculations and preferences of who in Ukraine would be capable leaders (SCMP Archive, 2014). Pointing to this as “evidence” of a “western backed coup” would basically follow the same logic of sports fans guilty of fixing the game if the team they were rooting for happened to win. Nonetheless, it is an old disinformation tactic that distracts from Russia’s real interference. Moscow has yet to produce any actual evidence of western involvement in the EuroMaidan protests of 2014. Nonetheless, the paranoia of foreign agents is used to justify Ukrainian genocide in the 21st century just as it did in the 1930s (Kovalev, 2022).

2. Ukrainians as a Deliberate Target

By 1930, the forced collectivization of farms, the banning of Ukrainian cultural symbols, and seizure of private property led to a growing resistance that began to resemble the peasant rebellion of 1919. In response to this unrest, in November 1932, Stalin launched a famine within the famine: a disaster specifically targeting Ukrainians. Several sets of directives blacklisted farms and entire villages for not reaching impossible grain quotas. When blacklisted, extensive searches were carried out by

With the rest of my generation, I firmly believed that the ends justified the means. Our great goal was the universal triumph of Communism, and for the sake of the goals everything was permissible—to lie, to steal, to destroy hundreds of thousands and even millions of people…everyone who stood in the way. (cited by Applebaum, 2017, p.138).

The mass arrests and deportation of Ukrainian peasants to gulags were the beginnings of the “dekulakization” process. But who was a kulak? In practice, it was anyone who withheld grain to feed themselves or their family or refused to join the collective farm.

Today, Stalinist linkage of Ukrainian nationalism and foreign interference still persists today. Following the old KGB playbook, Putin links any separation of Ukraine and Russia as artificial and part of a foreign conspiracy to attack the Russian Federation. Although Russia was the only foreign entity actively meddling in Ukraine’s internal affairs (see Part 2), Putin and his state-owned media insist that Ukraine’s 2004 and 2014 revolutions to rid themselves of Russian influence were in fact NATO/American led coups. A recorded telephone call between US assistant secretary Victoria Nuland and Ambassador Geoffrey Pyatt is frequently cited as ‘proof’ of western meddling. However, the dialogue never mentions actions or plans, only speculations and preferences of who in Ukraine would be capable leaders (SCMP Archive, 2014). Pointing to this as “evidence” of a “western backed coup” would basically follow the same logic of sports fans guilty of fixing the game if the team they were rooting for happened to win. Nonetheless, it is an old disinformation tactic that distracts from Russia’s real interference. Moscow has yet to produce any actual evidence of western involvement in the EuroMaidan protests of 2014. Nonetheless, the paranoia of foreign agents is used to justify Ukrainian genocide in the 21st century just as it did in the 1930s (Kovalev, 2022).

2. Ukrainians as a Deliberate Target

By 1930, the forced collectivization of farms, the banning of Ukrainian cultural symbols, and seizure of private property led to a growing resistance that began to resemble the peasant rebellion of 1919. In response to this unrest, in November 1932, Stalin launched a famine within the famine: a disaster specifically targeting Ukrainians. Several sets of directives blacklisted farms and entire villages for not reaching impossible grain quotas. When blacklisted, extensive searches were carried out by

| special brigades, soldiers, or secret policemen who cutoff all trade to the village, farm, or district. Everything edible was removed from the homes of millions of peasants, creating the famine now remembered as Holodomor. Unlike Russia and Belarus, where the term “blacklist” was limited to grain producers, only in Ukraine was it applied to whole districts. One historian wrote, “the blacklist became a universal weapon aimed at all rural residents” in Ukraine. “At that time neither Moscow nor other cities close to it |

were starving…only Ukraine was honored with this crown of thorns.” (Papakin cited by Applebaum, 2017, p.235-6). At least seventy-nine districts were blacklisted in Ukraine, and nearly half of the total districts in the entire republic were partially blacklisted. The only areas outside Ukraine’s borders that experienced blacklists were the Kuban in the North Caucasus, an historically Cossack and majority Ukrainian-speaking province (Papakin, n.d.).

This complete ban on trade and total confiscation of all foodstuffs effectively created ‘death zones’ where no one could survive. Stalin’s orders forced Ukrainian peasants to make a fatal choice: They could give up their grain reserve and starve to death, or they could hide some grain and risk execution or arrest—also resulting in starvation. The ban was soon so cruelly enforced that even kerosene, salt, matches, and even money were confiscated (Papakin, n.d.). Any peasant who might possess food would have no way to cook it. In January 1933, Stalin and Molotov closed the borders of the entire Soviet Ukraine and the heavily Ukrainian North Caucasus district. These border closures remained in place throughout the famine and gave the starving nowhere to go. These directives and others make it clear that genocide, not quotas, was the goal.

According to reports from survivors to a US Congressional investigation (1988), if it happened that soup was cooking, the activist inspectors would pull it off the stove and toss out the contents. By 1933, anyone not starving was by definition suspicious (p.341-2). Other survivors recall special boxes in their villages where people could deposit anonymous confessions or information as to the whereabouts of their neighbors’ hidden grain. It was common to inform, since when a person found someone else’s food, he or she was rewarded up to a third of it. During searches for food and money, violence was often used. Some were tortured and beaten till they gave up their last edibles. For good measure, rivers that contained wild fish were poisoned with carbolic acid, which the peasants ate anyway. (Applebaum, 2017, p.270-1). The members of these brigades sent to confiscate foodstuffs

This complete ban on trade and total confiscation of all foodstuffs effectively created ‘death zones’ where no one could survive. Stalin’s orders forced Ukrainian peasants to make a fatal choice: They could give up their grain reserve and starve to death, or they could hide some grain and risk execution or arrest—also resulting in starvation. The ban was soon so cruelly enforced that even kerosene, salt, matches, and even money were confiscated (Papakin, n.d.). Any peasant who might possess food would have no way to cook it. In January 1933, Stalin and Molotov closed the borders of the entire Soviet Ukraine and the heavily Ukrainian North Caucasus district. These border closures remained in place throughout the famine and gave the starving nowhere to go. These directives and others make it clear that genocide, not quotas, was the goal.

According to reports from survivors to a US Congressional investigation (1988), if it happened that soup was cooking, the activist inspectors would pull it off the stove and toss out the contents. By 1933, anyone not starving was by definition suspicious (p.341-2). Other survivors recall special boxes in their villages where people could deposit anonymous confessions or information as to the whereabouts of their neighbors’ hidden grain. It was common to inform, since when a person found someone else’s food, he or she was rewarded up to a third of it. During searches for food and money, violence was often used. Some were tortured and beaten till they gave up their last edibles. For good measure, rivers that contained wild fish were poisoned with carbolic acid, which the peasants ate anyway. (Applebaum, 2017, p.270-1). The members of these brigades sent to confiscate foodstuffs

| were increasingly replaced by ethnic Russians to ensure loyal enforcement. However, many quickly saw the gap between propaganda and reality. Victor Kravchenko noticed the “kulaks” were not rich, they were starving. Yet he did not protest. As many before him, he deliberately allowed himself to succumb to a form of intellectual blindness. Years later, he explained, “To spare yourself mental agony you veil |

unpleasant truths from view by half-closing your eyes—and your mind” (Kravchenko, 1947, p.91-2). The language of propaganda also helped mask reality. It helped persuade many activists to think of the peasants as second-class human beings—if they were even human at all. Afterall, Bolshivik ideology implied that they would soon disappear into history.

Other Soviet minorities were also targeted with famine. Violent resistance to collectivization in Central Asia, Kazakhstan, Tatarstan, and Bashiria was also understood to be anti-Soviet and counter revolutionary. Violent resistance also followed collectivization in the autonomous republics of Chechnya and Dagestan. (Martin, 2001, p.294-5). In Kazakhstan the regime blocked traditional nomadic routes and requisitioned livestock to feed the Russian cities, creating terrible suffering among the ethnic Kazakhs. More than a third of the entire population, 1.5 million people, perished during the famine that barely touched the Slavic population of Kazakhstan (Cameron, 2016). However, in Ukraine the strength of nationalism in the cities made the countryside more dangerous. All of the elements of rebellion were on display in Ukraine on the eve of the famine (Applebaum, 2017, p.187).

As a result, the Holodomor, in turn, delivered the predictable outcome: the Ukrainian national movement disappeared completely from Soviet politics and public life, and millions died leaving Ukrainian society completely destroyed.

3. Stalin’s Export of Ukrainian Grain Abroad

“Dizzying with Success” was the title of an article written by Stalin and published in Pravda on March 2, 1930. Not only was there no mention of famine, the policy of collective farming was going well and declared it was proceeding far better and far more quickly than expected. The USSR had already “overfilled” the Five Year Plan for collectivization that he still insisted was “voluntary.” Stories of murders and beating, the children left with no winter clothes all naturally went unmentioned to the general public, but were well-known inside the politburo. Additionally, the real numbers and evident failure of Stalin’s Five Year Plan was difficult to suppress amongst party leaders. Convinced of this fact, the Kremlin made what would turn out to be a disastrous and callous decision: to increase the export of grain, as well as of other food products, out of the Soviet Union in exchange for hard currency. According to Applebaum (2017):

“Between 1929 and 1931, Soviet grain exports to Germany tripled… Foreshadowing the future Soviet (and Russian) use of gas as a weapon of influence, the Bolsheviks also began asking for political favors in response to large shipments of relatively low-priced grain” (p.193).

The Soviets valued hard currency over human life. It was desired to purchase factory machine parts to meet Stalin’s 5 year plan. According to Davies & Wheatcroft (2010), the spring sowing of 1931 was hampered by shortages of horses, tractors, and seeds. Worse, the Volga region, Siberia, and Kazakhstan all suffered from drought, as did central Ukraine. By September it was obvious the 1931 harvest would be much smaller than the previous year. However, Soviet leadership fixated their concern that the country would not meet its export quotas. Everyone understood, at some level, that collectivization was itself the source of the new shortage. Instead, Ukrainian peasants were scapegoated and punished with ever increasing quotas. Since the harvest had been unsatisfactory in the Urals, the Volga, Kazakhstan and western Siberia; Ukrainians in particular would have to collect not only their original grain quota, but also an extra amount of seed grain for an impossible quota (Davies & Wheatcroft, 2010, p.48-78). In short, there was enough food to feed the starving; however, Stalin chose to export Ukraine’s food and increase their already impossible quotas, ensuring genocide.

4. Stalin Knew

Many Ukrainian communist leaders knew what was to come. One local official wrote, “The Bolsheviks have never robbed Ukraine as thoroughly and as cynical as they do now. Without questions, there will be famine…” (Lebenko, cited by Applebaum, 2017, p.131). Instead of solving the problem, the Kremlin sought to eliminate the dissidents.

Even so, some in the OGPU felt uneasy about how quickly the definition of kulak had evolved. In a note to Stalin in March 1930, the deputy director of the secret police feared that “middle-income peasants, poor peasants, and even farm laborers and workers” were falling into the “kulak” category. (Yagoda cited by Applebaum, 2017, p.148). Policemen on the ground given arrest quotas, whether they were able to identify kulaks or not. If they could not find them, they would have to be created. The highest numbers for arrests and deportations were always in Ukraine (Viola & Danilov, 2005, p.240-1).

Other Soviet minorities were also targeted with famine. Violent resistance to collectivization in Central Asia, Kazakhstan, Tatarstan, and Bashiria was also understood to be anti-Soviet and counter revolutionary. Violent resistance also followed collectivization in the autonomous republics of Chechnya and Dagestan. (Martin, 2001, p.294-5). In Kazakhstan the regime blocked traditional nomadic routes and requisitioned livestock to feed the Russian cities, creating terrible suffering among the ethnic Kazakhs. More than a third of the entire population, 1.5 million people, perished during the famine that barely touched the Slavic population of Kazakhstan (Cameron, 2016). However, in Ukraine the strength of nationalism in the cities made the countryside more dangerous. All of the elements of rebellion were on display in Ukraine on the eve of the famine (Applebaum, 2017, p.187).

As a result, the Holodomor, in turn, delivered the predictable outcome: the Ukrainian national movement disappeared completely from Soviet politics and public life, and millions died leaving Ukrainian society completely destroyed.

3. Stalin’s Export of Ukrainian Grain Abroad

“Dizzying with Success” was the title of an article written by Stalin and published in Pravda on March 2, 1930. Not only was there no mention of famine, the policy of collective farming was going well and declared it was proceeding far better and far more quickly than expected. The USSR had already “overfilled” the Five Year Plan for collectivization that he still insisted was “voluntary.” Stories of murders and beating, the children left with no winter clothes all naturally went unmentioned to the general public, but were well-known inside the politburo. Additionally, the real numbers and evident failure of Stalin’s Five Year Plan was difficult to suppress amongst party leaders. Convinced of this fact, the Kremlin made what would turn out to be a disastrous and callous decision: to increase the export of grain, as well as of other food products, out of the Soviet Union in exchange for hard currency. According to Applebaum (2017):

“Between 1929 and 1931, Soviet grain exports to Germany tripled… Foreshadowing the future Soviet (and Russian) use of gas as a weapon of influence, the Bolsheviks also began asking for political favors in response to large shipments of relatively low-priced grain” (p.193).

The Soviets valued hard currency over human life. It was desired to purchase factory machine parts to meet Stalin’s 5 year plan. According to Davies & Wheatcroft (2010), the spring sowing of 1931 was hampered by shortages of horses, tractors, and seeds. Worse, the Volga region, Siberia, and Kazakhstan all suffered from drought, as did central Ukraine. By September it was obvious the 1931 harvest would be much smaller than the previous year. However, Soviet leadership fixated their concern that the country would not meet its export quotas. Everyone understood, at some level, that collectivization was itself the source of the new shortage. Instead, Ukrainian peasants were scapegoated and punished with ever increasing quotas. Since the harvest had been unsatisfactory in the Urals, the Volga, Kazakhstan and western Siberia; Ukrainians in particular would have to collect not only their original grain quota, but also an extra amount of seed grain for an impossible quota (Davies & Wheatcroft, 2010, p.48-78). In short, there was enough food to feed the starving; however, Stalin chose to export Ukraine’s food and increase their already impossible quotas, ensuring genocide.

4. Stalin Knew

Many Ukrainian communist leaders knew what was to come. One local official wrote, “The Bolsheviks have never robbed Ukraine as thoroughly and as cynical as they do now. Without questions, there will be famine…” (Lebenko, cited by Applebaum, 2017, p.131). Instead of solving the problem, the Kremlin sought to eliminate the dissidents.

Even so, some in the OGPU felt uneasy about how quickly the definition of kulak had evolved. In a note to Stalin in March 1930, the deputy director of the secret police feared that “middle-income peasants, poor peasants, and even farm laborers and workers” were falling into the “kulak” category. (Yagoda cited by Applebaum, 2017, p.148). Policemen on the ground given arrest quotas, whether they were able to identify kulaks or not. If they could not find them, they would have to be created. The highest numbers for arrests and deportations were always in Ukraine (Viola & Danilov, 2005, p.240-1).

the OGPU raised the alarm: more than 40,000 households were not going to plant anything at all. Hunger caused many to be too weak to work the fields. In February, Hryhorii Petrovskyi, chairman of Ukraine’s Supreme Soviet—-wrote a letter to his colleagues asking to halt grain collections in Ukraine and restore free exchange of goods, call upon the Red Cross and other emergency relief organizations, especially for children, to help out famine-struck regions in Ukraine. Bluntly, he declared that the Soviet state should expect to collect nothing from Ukraine. Any food harvested should remain in Ukraine to feed its starving population (Applebaum, 2017, p.205). In spite of all the clear warnings, Stalin actually withdrew millet and other food aid to Ukraine. He also demanded that the Ukrainian Communist Party maintain its policy of confiscating tractors and other equipment from underperforming farms. Petrovskyi wrote again:

“We knew beforehand that fulfilling state grain procurements in Ukraine would be difficult…Why did they take away all of the sowing seeds? That did not happen even under the old regime…Why isn’t bread being brought here?” (cited by Applebaum, 2017, p.209).

Molotov also wrote Stalin and suggested a suspension of the grain exports so as to provide Ukraine with some food aid. Stalin argued back, “In my opinion, Ukraine has been given more than enough…” (cited p.210). Stalin found a political interpretation for all acts of desperation. The theft of even tiny morsels of food could be punished by ten years in a labor camp or death, a punishment previously reserved for treason. By 1932, the harvest was 60 percent lower than expected (Davies & Wheatcroft, 2010). Yet, in August it was brought to Stalin’s attention that many Ukrainian party members were refusing to carry out orders to confiscate grain from starving peasant families. In a letter to communist leaders in Ukraine, he wrote: “Give yourself the task of quickly transforming Ukraine into a true fortress of the USSR, a truly model republic” (cited by Applebaum, 2017, p.220). He believed that this was the moment to revive Lenin’s tactics from 1919. “Without these and similar measures (ideological and political work in Ukraine, above all in her border districts and so forth) I repeat—we could lose Ukraine…” (Stalin cited by Martin, 2001, p.298), betraying his ultimate motive. Stalin could have sent food relief. Instead, he began using stark language about Ukraine as well as the North Caucasus, a Russian province that was heavily Ukrainian.

In full context, the Ukrainian Communist Party was a tool of Moscow, with no autonomy or any ability to make decisions on its own. Stalin knew the Ukrainians would fail to meet his impossible quotas and he knew that the ‘blacklistings’ being used were starving Ukrainians to death. Nor did exports of other kinds of food stop while they starved. He allowed them to continue for several fatal months, during which time millions died.

5. Colonizing Ukraine with Ethnic Russians

After the village of Hordyshche in Voroshilov district, Donetsk province was blacklisted in November 1932, local authorities noticed the rules were not having much impact. The village had a large railway station nearby where illicit trading took place—providing much needed products. In light of this discovery, the whole area received extra sanctions. 150 people were dismissed from their jobs in local factories, their houses were confiscated and given to “industrial laborers in need of accommodations,” and the collective farm leadership was put on trial (Papkin, p.11). By November 1933 Moscow established death sentences for party and collective leaders who had failed to meet their grain quotas. As these Ukrainian peasants died off or were taken away to gulags, demobilized Red Army soldiers and other outsiders from the Soviet Union (mostly ethnic Russians) replaced them (Applebaum, 2017, p.232). Later in 1933, the regime launched a resettlement program that resulted in the replacement of Ukrainians with Russians to fill the labor shortage (p.343).

These settlements coincided with the abolishment of Ukrainian history and language courses and eliminated Ukrainian textbooks. Ukrainian teachers were charged with trying to “Ukrainize” Russian children by force. In truth it was not forced nor were the children Russian. Some 4,000 teachers were named as “class-hostile enemies.” Across Ukraine, nearly 200,000 people were arrested who held any links to Ukrainian culture, language, religion, or education (Graziosi et al., 2013, p.9). Witnesses at the time were already drawing links between the famine and the nationalist movement. According to Mykola Khvylovyi, the famine was a political construction “designed to solve a very dangerous Ukrainian problem all at once.” (cited by Applebaum, 2017, p.257). Millions of Ukrainians assumed anyone associated with Ukrainian language or history was dangerous, as well as “backwards” and inferior. The city government of Donetsk dropped Ukrainian entirely and factory newspapers that had been publishing in Ukrainian switched to Russian. Gradenigo, the Italian consult who lived in Kharkiv understood the famine and its political intent. “The current disaster will lead to the colonization of Ukraine by Russians. It will transform Ukraine’s character…simply because there will be no more “Ukrainian problem” when Ukraine becomes an indistinguishable part of Russia…” (cited by Applebaum, 2017, p.363).

The Scale

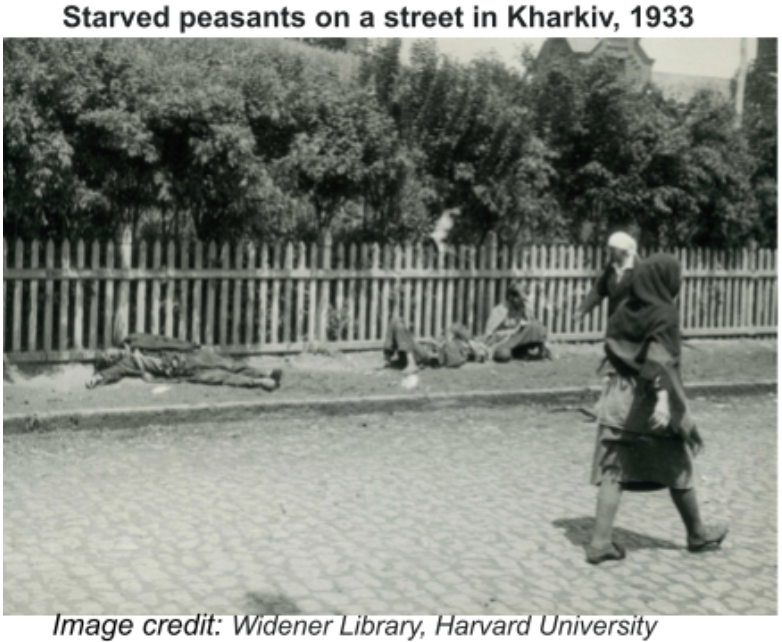

Multiple witnesses in Kyiv and Kharkiv recalled the trucks cruising the city at that time with men pulling the dead off the streets and loading them onto their vehicles in manner which suggests no one would give much thought to counting them.

“We knew beforehand that fulfilling state grain procurements in Ukraine would be difficult…Why did they take away all of the sowing seeds? That did not happen even under the old regime…Why isn’t bread being brought here?” (cited by Applebaum, 2017, p.209).

Molotov also wrote Stalin and suggested a suspension of the grain exports so as to provide Ukraine with some food aid. Stalin argued back, “In my opinion, Ukraine has been given more than enough…” (cited p.210). Stalin found a political interpretation for all acts of desperation. The theft of even tiny morsels of food could be punished by ten years in a labor camp or death, a punishment previously reserved for treason. By 1932, the harvest was 60 percent lower than expected (Davies & Wheatcroft, 2010). Yet, in August it was brought to Stalin’s attention that many Ukrainian party members were refusing to carry out orders to confiscate grain from starving peasant families. In a letter to communist leaders in Ukraine, he wrote: “Give yourself the task of quickly transforming Ukraine into a true fortress of the USSR, a truly model republic” (cited by Applebaum, 2017, p.220). He believed that this was the moment to revive Lenin’s tactics from 1919. “Without these and similar measures (ideological and political work in Ukraine, above all in her border districts and so forth) I repeat—we could lose Ukraine…” (Stalin cited by Martin, 2001, p.298), betraying his ultimate motive. Stalin could have sent food relief. Instead, he began using stark language about Ukraine as well as the North Caucasus, a Russian province that was heavily Ukrainian.

In full context, the Ukrainian Communist Party was a tool of Moscow, with no autonomy or any ability to make decisions on its own. Stalin knew the Ukrainians would fail to meet his impossible quotas and he knew that the ‘blacklistings’ being used were starving Ukrainians to death. Nor did exports of other kinds of food stop while they starved. He allowed them to continue for several fatal months, during which time millions died.

5. Colonizing Ukraine with Ethnic Russians

After the village of Hordyshche in Voroshilov district, Donetsk province was blacklisted in November 1932, local authorities noticed the rules were not having much impact. The village had a large railway station nearby where illicit trading took place—providing much needed products. In light of this discovery, the whole area received extra sanctions. 150 people were dismissed from their jobs in local factories, their houses were confiscated and given to “industrial laborers in need of accommodations,” and the collective farm leadership was put on trial (Papkin, p.11). By November 1933 Moscow established death sentences for party and collective leaders who had failed to meet their grain quotas. As these Ukrainian peasants died off or were taken away to gulags, demobilized Red Army soldiers and other outsiders from the Soviet Union (mostly ethnic Russians) replaced them (Applebaum, 2017, p.232). Later in 1933, the regime launched a resettlement program that resulted in the replacement of Ukrainians with Russians to fill the labor shortage (p.343).

These settlements coincided with the abolishment of Ukrainian history and language courses and eliminated Ukrainian textbooks. Ukrainian teachers were charged with trying to “Ukrainize” Russian children by force. In truth it was not forced nor were the children Russian. Some 4,000 teachers were named as “class-hostile enemies.” Across Ukraine, nearly 200,000 people were arrested who held any links to Ukrainian culture, language, religion, or education (Graziosi et al., 2013, p.9). Witnesses at the time were already drawing links between the famine and the nationalist movement. According to Mykola Khvylovyi, the famine was a political construction “designed to solve a very dangerous Ukrainian problem all at once.” (cited by Applebaum, 2017, p.257). Millions of Ukrainians assumed anyone associated with Ukrainian language or history was dangerous, as well as “backwards” and inferior. The city government of Donetsk dropped Ukrainian entirely and factory newspapers that had been publishing in Ukrainian switched to Russian. Gradenigo, the Italian consult who lived in Kharkiv understood the famine and its political intent. “The current disaster will lead to the colonization of Ukraine by Russians. It will transform Ukraine’s character…simply because there will be no more “Ukrainian problem” when Ukraine becomes an indistinguishable part of Russia…” (cited by Applebaum, 2017, p.363).

The Scale

Multiple witnesses in Kyiv and Kharkiv recalled the trucks cruising the city at that time with men pulling the dead off the streets and loading them onto their vehicles in manner which suggests no one would give much thought to counting them.

| School teachers witnessed children dying during lessons. Another survivor recalled the roads to Donbas being lined with corpses. “There were more bodies than people to move them.” (U.S. Congressional Report, 1988). Hunger led to hallucinations and emotional changes, and especially the disappearance of family feelings. Distrust grew too. “Neighbors had been made to spy on neighbors,” wrote Dolot (1987): “friends had been forced to betray friends; children had been taught to denounce their parents. The |

traditional hospitality of the villagers had disappeared, to be replaced by mistrust and suspicion” (p.92). Iaryna Mytsyk remembered, “Centuries-old sincerity and generosity did not exist anymore. It disappeared with hungry stomachs.” No one knew who might turn out to be a thief, a spy—or a cannibal. (cited by Applebaum, 2017, p.292). Hunger made everyone motionless and unable to think. As winter ended and Spring began in 1933, the dead began to thaw and “the air was filled with the ubiquitous odor of decomposing bodies. The wind carried the odor far and wide, all across Ukraine.” (Boriak cited by Applebaum, 2017, p.302).

The Cover up

The coverup of Holodomor required an extraordinary effort on the part of numerous people over many years. Most archival materials from Ukraine in this period, such as death registries were destroyed (Applebaum, 2017, p.356). At night, the living and the dead in Kharkiv would be loaded onto trucks, driven to a ravine outside town and thrown into it. To conceal the horror, most of the body collection teams worked at night and buried them in secret. Mass graves of famine victims were covered up and hidden, and it became dangerous even to know where they were located. In 1938 all the staff of the Lukianivske cemetery in Kyiv were arrested, tried and shot as counter-revolutionary insurgents, probably to prevent them from revealing what they knew (p.303). The OGPU leadership in Ukraine warned their subordinates against putting too much information about the famine into writing. (Werth, 2008 cited by Applebaum, 2017, p.307). Nevertheless, the secret police, the ordinary criminal police, and other local officials did keep records. The OGPU in Kyiv were receiving at least ten reports of cannibalism every day; however, their only concerns were the ‘political’ impact the spread of these stories might have. After recording how mothers ate their own children and siblings ate siblings, the OGPU reported with satisfaction that the incident had sparked no “unhealthy chatter” (p.308).

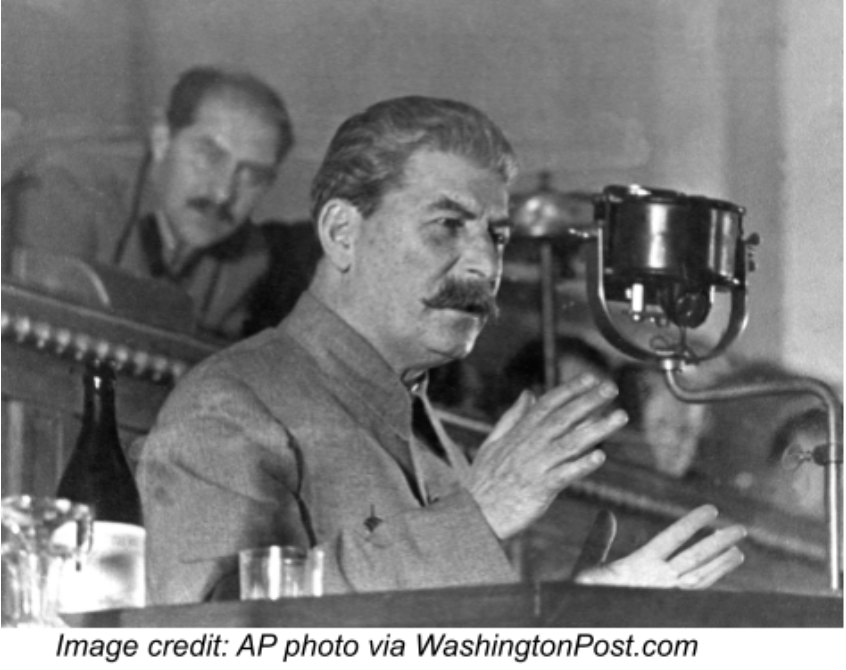

Although mortality statistics were generally accurate in 1933, the authorities later altered death registries across Ukraine to hide the numbers of deaths from starvation, and in 1937 scrapped an entire census because of what it revealed. Those in charge of the census who knew the truth were arrested months later and executed. Even before the census was finished, Stalin declared, “...an astonishing rapid, never-before-seen increase in population is taking place” (cited by Applebaum, 2017, p.359). Overtime, Soviet statisticians found ways to match the census with the rhetoric by relocating Soviet citizens from elsewhere to settle in Ukraine. Thanks to the work of modern researchers, using what census data existed both before and after the famine and tracking migrations, they have now brought the total to 4.5 million missing Ukrainians. Overall their data show that the famine touched Russia far less than Ukraine, with an overall 3% “excess deaths” in rural Russia, as against 14.9% in rural Ukraine (Rudnytskyi et al., 2015, p.65). Furthermore, Jews, Germans, and Poles survived at a much higher rate as well since they were not perceived to be part of the Ukrainian national movement, and thus were not particular targets of the repressive wave of 1932-3 (Applebaum, 2017, p.335).

Western Accomplices

In the 1930s, the problem for the West was not evidence, but self interest and politics which ultimately led to our collective complicity in the coverup. The Vatican received both written and rare photographic evidence of the famine which was smuggled by an Austrian engineer in Kharkiv. However, Hitler’s January 1933 electoral victory created a political trap where the hierarchy feared that strong language about the Soviet famine would make it seem as if the Pope favored Nazi Germany. The Holy See mostly kept silent as a result. (McVay & Luciuk, 2011, p.8-9).

Foreign diplomats in Moscow also kept their silence, preferring not to ruffle feathers and risk access to the Kremlin. Others had mixed motives. Edouard Herriot a French Radical politician was invited to Ukraine at the end of August 1933 specifically to repudiate growing rumors of famine. He wanted to encourage his country’s trade relations with the USSR. During his visit, he saw shops whose shelves had been hastily stocked in advance and met enthusiastic peasants coached especially for the occasion. “I’ve traveled across Ukraine,” declared Herriot, “I assure you that I have seen a garden in full bloom.” (Thevenin, 2005 cited by Applebaum, 2017, p.368).

The Cover up

The coverup of Holodomor required an extraordinary effort on the part of numerous people over many years. Most archival materials from Ukraine in this period, such as death registries were destroyed (Applebaum, 2017, p.356). At night, the living and the dead in Kharkiv would be loaded onto trucks, driven to a ravine outside town and thrown into it. To conceal the horror, most of the body collection teams worked at night and buried them in secret. Mass graves of famine victims were covered up and hidden, and it became dangerous even to know where they were located. In 1938 all the staff of the Lukianivske cemetery in Kyiv were arrested, tried and shot as counter-revolutionary insurgents, probably to prevent them from revealing what they knew (p.303). The OGPU leadership in Ukraine warned their subordinates against putting too much information about the famine into writing. (Werth, 2008 cited by Applebaum, 2017, p.307). Nevertheless, the secret police, the ordinary criminal police, and other local officials did keep records. The OGPU in Kyiv were receiving at least ten reports of cannibalism every day; however, their only concerns were the ‘political’ impact the spread of these stories might have. After recording how mothers ate their own children and siblings ate siblings, the OGPU reported with satisfaction that the incident had sparked no “unhealthy chatter” (p.308).

Although mortality statistics were generally accurate in 1933, the authorities later altered death registries across Ukraine to hide the numbers of deaths from starvation, and in 1937 scrapped an entire census because of what it revealed. Those in charge of the census who knew the truth were arrested months later and executed. Even before the census was finished, Stalin declared, “...an astonishing rapid, never-before-seen increase in population is taking place” (cited by Applebaum, 2017, p.359). Overtime, Soviet statisticians found ways to match the census with the rhetoric by relocating Soviet citizens from elsewhere to settle in Ukraine. Thanks to the work of modern researchers, using what census data existed both before and after the famine and tracking migrations, they have now brought the total to 4.5 million missing Ukrainians. Overall their data show that the famine touched Russia far less than Ukraine, with an overall 3% “excess deaths” in rural Russia, as against 14.9% in rural Ukraine (Rudnytskyi et al., 2015, p.65). Furthermore, Jews, Germans, and Poles survived at a much higher rate as well since they were not perceived to be part of the Ukrainian national movement, and thus were not particular targets of the repressive wave of 1932-3 (Applebaum, 2017, p.335).

Western Accomplices

In the 1930s, the problem for the West was not evidence, but self interest and politics which ultimately led to our collective complicity in the coverup. The Vatican received both written and rare photographic evidence of the famine which was smuggled by an Austrian engineer in Kharkiv. However, Hitler’s January 1933 electoral victory created a political trap where the hierarchy feared that strong language about the Soviet famine would make it seem as if the Pope favored Nazi Germany. The Holy See mostly kept silent as a result. (McVay & Luciuk, 2011, p.8-9).

Foreign diplomats in Moscow also kept their silence, preferring not to ruffle feathers and risk access to the Kremlin. Others had mixed motives. Edouard Herriot a French Radical politician was invited to Ukraine at the end of August 1933 specifically to repudiate growing rumors of famine. He wanted to encourage his country’s trade relations with the USSR. During his visit, he saw shops whose shelves had been hastily stocked in advance and met enthusiastic peasants coached especially for the occasion. “I’ve traveled across Ukraine,” declared Herriot, “I assure you that I have seen a garden in full bloom.” (Thevenin, 2005 cited by Applebaum, 2017, p.368).

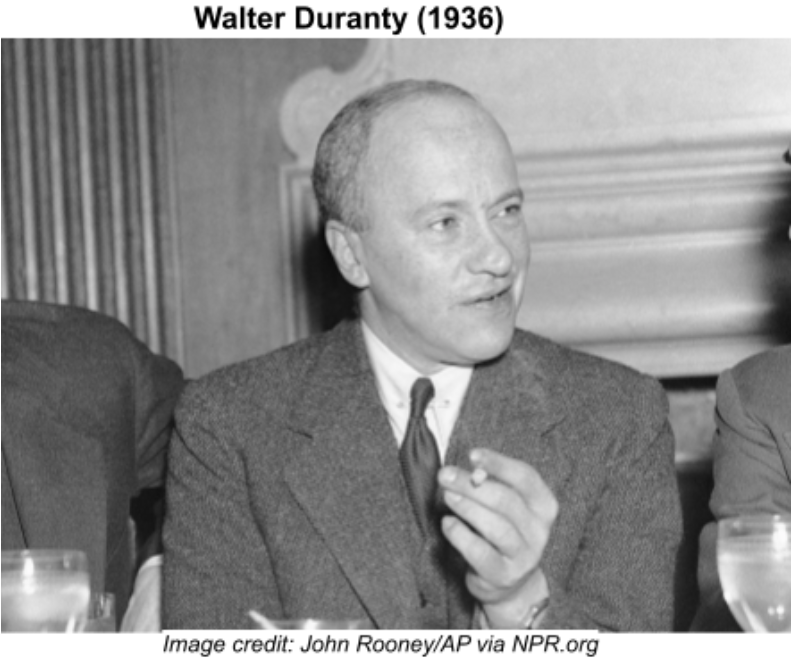

| Some earned extra rewards for playing the game. Walter Duranty of The New York Times in Moscow was made relatively rich and famous for his coverage of the famine. Playing the role of the skeptical “realist” trying to listen to both sides of the story rather than facts wrote, “it is true that the lot of kulaks and other who have opposed the Soviet experiment is not a happy one,” he wrote in 1935. “In both cases, the suffering inflicted is done with a noble purpose.” Duranty twice received exclusive interviews |

with Stalin. In 1932, his series of articles on the success of collectivisation and the Five Year Plan won him the Pulitzer Prize. (Duranty, 1935 cited by Applebaum, 2017, p.370). Moscow correspondent Eugene Lyons wrote years later that all foreigners were well aware of what was happening in Ukraine as well as in Kazakhstan and the Volga region. Everyone knew, yet no one mentioned it. (Lyons, 1937, p.574).

The Poles, who had very detailed information on the famine from multiple sources, also remained silent. They had signed a nonaggression pact with the USSR in July 1932 and worked hard to preserve the peace, which would backfire in 1939. (Snyder, 2012, p.50). Finally, even the United States had reasons to keep its silence as the new Roosevelt administration was actively ignoring bad news from the Soviet Union in order to open diplomatic ties to counter the growing threat posed by Germany and Japan. (Applebaum, 2017, p.380).

As for Ukrainians, decades of Soviet occupation made it forbidden to speak about what had happened. Although no one could publicly mourn, the private trauma and memories could not be censored. This gap between private and public memory distressed Ukrainians for decades. In 1961, several Ukrainian academics were arrested for attempting to research the famine. However, some activists and war refugees managed to contact Radio Liberty with their accounts, which put together a documentary called Harvest of Despair (1985) followed by a book adaptation by historian Robert Conquest (p.402). This sparked an angry letter from the Secretary to the Soviet Embassy of Canada to the Toronto Globe: “Yes, some had starved, but they were the victims of drought and kulak sabotage” (cited by Appplebaum, 2017, p.403). A more elaborate Soviet response arrived in 1987, with the publication of Fraud, Famine and Fascism: The Ukrainian Genocide Myth from Hitler to Harvard. The book described the famine as a hoax invented and promoted by Ukrainian fascists and western conspirators. Although the publication failed to provide real evidence linking Holodomor to a Nazi propaganda drive, it found a receptive audience among western socialists who feared Stalin’s genocide of Ukrainians might be used to discredit Marxism. (p.403). Furthermore, the book was a harbinger for what was to come in 2014. The old Soviet playbook always linked any argument built around Ukrainian nationalism to some nefarious foreign plot. Now that the USSR is no more, the language of the 1930s simply shifted from bourgeois/kulak plots aided by Polish agents, to now neo-Nazis brigades aided by the CIA.

Conclusion

Holodomor marked the end of the Ukrainian national movement in the Soviet Union. The man-made famine was a clear attack on the Soviet Union’s ethnic minorities. Suspicion of loyalty contributed to the higher death rates of peasants in Ukraine, Kazakhstan, and the North Caucasus. But nowhere else were agricultural failures linked so explicitly to questions of national language or culture as they were in both Ukraine and in the North Caucasus, with its large Ukrainian-speaking population. The first decree blamed the failure to procure grain in both Ukraine and the North Caucasus on the “poor efforts and absence of revolutionary vigilance.” Their alleged counter-revolutionary sabotage was behind the failure of the Soviet system. The only admitted fault of the Soviet Union was the short lived “Ukrainization” policy which provided “the enemies of Soviet power” with a legitimate cover (Martin, 2001, p.303). To authorize an immediate halt to any Ukrainization anywhere, regions were ordered to stop printing Ukrainian newspapers and books immediately, and to impose Russian as the main language of school instruction. The decrees themselves established a direct link between the assault on Ukrainian national identity and the famine. The same secret police organization carried them out. The same officials oversaw the propaganda that described them (Applebaum, 2017, p.247).

Today, even as Russia’s former KGB dictator continues the historic continuity of genocide towards Ukrainians, his efforts could not have been possible without the willing complicity of western journalists who value ratings over facts. Thanks to the internet, conspiracy theories and political intrigue are a billion dollar industry. There is no shortage of modern Walter Durantys in today’s political climate, ready to profit from Putin’s falsehoods if it agitates enough viewers to stay tuned during commercial breaks.

Courageously, despite all the gaslighting, one thing is clear (as their national anthem defiantly proclaims): “Ukraine is not gone yet.” Against all odds. All the centuries of oppression. All the disinformation. All the war crimes. Ukraine still exists…but they need our help.

The Poles, who had very detailed information on the famine from multiple sources, also remained silent. They had signed a nonaggression pact with the USSR in July 1932 and worked hard to preserve the peace, which would backfire in 1939. (Snyder, 2012, p.50). Finally, even the United States had reasons to keep its silence as the new Roosevelt administration was actively ignoring bad news from the Soviet Union in order to open diplomatic ties to counter the growing threat posed by Germany and Japan. (Applebaum, 2017, p.380).

As for Ukrainians, decades of Soviet occupation made it forbidden to speak about what had happened. Although no one could publicly mourn, the private trauma and memories could not be censored. This gap between private and public memory distressed Ukrainians for decades. In 1961, several Ukrainian academics were arrested for attempting to research the famine. However, some activists and war refugees managed to contact Radio Liberty with their accounts, which put together a documentary called Harvest of Despair (1985) followed by a book adaptation by historian Robert Conquest (p.402). This sparked an angry letter from the Secretary to the Soviet Embassy of Canada to the Toronto Globe: “Yes, some had starved, but they were the victims of drought and kulak sabotage” (cited by Appplebaum, 2017, p.403). A more elaborate Soviet response arrived in 1987, with the publication of Fraud, Famine and Fascism: The Ukrainian Genocide Myth from Hitler to Harvard. The book described the famine as a hoax invented and promoted by Ukrainian fascists and western conspirators. Although the publication failed to provide real evidence linking Holodomor to a Nazi propaganda drive, it found a receptive audience among western socialists who feared Stalin’s genocide of Ukrainians might be used to discredit Marxism. (p.403). Furthermore, the book was a harbinger for what was to come in 2014. The old Soviet playbook always linked any argument built around Ukrainian nationalism to some nefarious foreign plot. Now that the USSR is no more, the language of the 1930s simply shifted from bourgeois/kulak plots aided by Polish agents, to now neo-Nazis brigades aided by the CIA.

Conclusion

Holodomor marked the end of the Ukrainian national movement in the Soviet Union. The man-made famine was a clear attack on the Soviet Union’s ethnic minorities. Suspicion of loyalty contributed to the higher death rates of peasants in Ukraine, Kazakhstan, and the North Caucasus. But nowhere else were agricultural failures linked so explicitly to questions of national language or culture as they were in both Ukraine and in the North Caucasus, with its large Ukrainian-speaking population. The first decree blamed the failure to procure grain in both Ukraine and the North Caucasus on the “poor efforts and absence of revolutionary vigilance.” Their alleged counter-revolutionary sabotage was behind the failure of the Soviet system. The only admitted fault of the Soviet Union was the short lived “Ukrainization” policy which provided “the enemies of Soviet power” with a legitimate cover (Martin, 2001, p.303). To authorize an immediate halt to any Ukrainization anywhere, regions were ordered to stop printing Ukrainian newspapers and books immediately, and to impose Russian as the main language of school instruction. The decrees themselves established a direct link between the assault on Ukrainian national identity and the famine. The same secret police organization carried them out. The same officials oversaw the propaganda that described them (Applebaum, 2017, p.247).

Today, even as Russia’s former KGB dictator continues the historic continuity of genocide towards Ukrainians, his efforts could not have been possible without the willing complicity of western journalists who value ratings over facts. Thanks to the internet, conspiracy theories and political intrigue are a billion dollar industry. There is no shortage of modern Walter Durantys in today’s political climate, ready to profit from Putin’s falsehoods if it agitates enough viewers to stay tuned during commercial breaks.

Courageously, despite all the gaslighting, one thing is clear (as their national anthem defiantly proclaims): “Ukraine is not gone yet.” Against all odds. All the centuries of oppression. All the disinformation. All the war crimes. Ukraine still exists…but they need our help.

References

Applebaum, A. (2017). Red Famine: Stalin’s War on Ukraine. Anchor Books.

Cameron, S. (2016). Kazakh Famine of 1932–33: Current research and new directions. East/West Journal of Ukrainian Studies. 3(2) 117. DOI:10.21226/T2T59X https://www.researchgate.net/publication/308010845_The_Kazakh_Famine_of_1930-33_Current_Research_and_New_Directions

Davies, R. & Wheatcroft, S. (2010). The Years of Hunger: Soviet Agriculture, 1931-1933. Palgrave Macmillan. https://diasporiana.org.ua/wp-content/uploads/books/22207/file.pdf

Dolot, M. (1987). Execution by Hunger: The Hidden Holocaust. W. W. Norton & Company.

Graziosi, A., Hajda, L., & Hryn, H. (2013). After the Holodomor: the enduring impact of the great famine on Ukraine. Harvard University Press.

Grossman. V. (1961). Everything Flows. Vintage Classics.

Johnson, B. (2017). Russia still denies the Holodomor was ‘genocide.’ Transatlantic Blog. https://www.acton.org/publications/transatlantic/2017/11/27/russia-still-denies-holodomor-was-genocide

Kotkin, S. (2015). Stalin: Paradoxes of Power, 1878-1928. Penguin Books.

Kovalev, A. (2022, April). Russia’s Ukraine Propaganda Has Turned Fully Genocidal. Foreign Policy. https://foreignpolicy.com/2022/04/09/russia-putin-propaganda-ukraine-war-crimes-atrocities/

Kravchenko, V. (1947). I Chose Freedom. Garden City Publishing.

Lyons, E. (1937). Assignment in Utopia. Harcourt, Brace and Company. https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.89424/page/n587/mode/2up

Martin, T. (2001). Affirmative Action Empire. Cornell University Press.

McVay, A. & Luciuk, L. Y. (2011). The Holy See and the Holodomor: Documents from the Vatican Secret Archives on the Great Famine of 1932-1933 in Soviet Ukraine. Kashtan Press.

Papakin, H. (n.d.). Blacklists as an Instrument of the Famine-Genocide of 1932-1933 in Ukraine (M. Olynyk, trans.). Key Articles on the Holodomor Translated from Ukrainian into English. Holodomor Research and Education Consortium, 2-3. https://holodomor.ca/resources/further-reading/translated-academic-articles/

Rudnytskyi, O., Levchuk, N., Wolowyna, O., Shevchuk, P., & Kovbasiuk, A. (2015). Demography of a man-made human catastrophe: The case of massive famine in Ukraine 1932-1933. Canadian Studies in Population [ARCHIVES], 42(1-2), 53-80. https://gis.huri.harvard.edu/sites/hwpi.harvard.edu/files/mapa/files/csp-42.pdf?m=1607385802

SCMP Archive. (2014, February 7). Recorded conversation between Asst. Sec. of State Victoria Nuland and Amb. Jeffery Pyatt [video] YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JoW75J5bnnE

Shkandrij, M., & Bertelsen, O. (2013). The Soviet Regime’s National Operations in Ukraine, 1929–1934. Canadian Slavonic Papers, 55(3-4), 417-447.

Snyder, T. (2012). Bloodlands: Europe Between Hitler and Stalin. Basic Books.

Stalin, J. V. (1925). Concerning the National Question in Yugoslavia, Speech Delivered in the Yugoslav Commission of the ECCI, March 30, 1925. Stalin, Works, v7, 71-2. https://www.marxists.org/reference/archive/stalin/works/1925/03/30.htm

Stalin, J. V. (1930). Dizzy with Success: Concerning questions of the collective-farm movement (K. Higham & Mike B., trans.) Pravda. March 2, 1930. Stalin, Works, v12, 197-205. https://www.marxists.org/reference/archive/stalin/works/1930/03/02.htm

United States Congress & Commission on the Ukraine Famine. (1988). Investigation into the Ukrainian Famine, 1932-1933. Report to Congress. U.S. Government Printing Office. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=umn.31951d00831044s&view=1up&seq=1

Viola, L. & Danilov, V. P. (2005). The War Against the Peasantry, 1927-1930: The Tragedy of the Soviet Countryside, Vol. 1. Yale University Press.

Applebaum, A. (2017). Red Famine: Stalin’s War on Ukraine. Anchor Books.

Cameron, S. (2016). Kazakh Famine of 1932–33: Current research and new directions. East/West Journal of Ukrainian Studies. 3(2) 117. DOI:10.21226/T2T59X https://www.researchgate.net/publication/308010845_The_Kazakh_Famine_of_1930-33_Current_Research_and_New_Directions

Davies, R. & Wheatcroft, S. (2010). The Years of Hunger: Soviet Agriculture, 1931-1933. Palgrave Macmillan. https://diasporiana.org.ua/wp-content/uploads/books/22207/file.pdf

Dolot, M. (1987). Execution by Hunger: The Hidden Holocaust. W. W. Norton & Company.

Graziosi, A., Hajda, L., & Hryn, H. (2013). After the Holodomor: the enduring impact of the great famine on Ukraine. Harvard University Press.

Grossman. V. (1961). Everything Flows. Vintage Classics.

Johnson, B. (2017). Russia still denies the Holodomor was ‘genocide.’ Transatlantic Blog. https://www.acton.org/publications/transatlantic/2017/11/27/russia-still-denies-holodomor-was-genocide

Kotkin, S. (2015). Stalin: Paradoxes of Power, 1878-1928. Penguin Books.

Kovalev, A. (2022, April). Russia’s Ukraine Propaganda Has Turned Fully Genocidal. Foreign Policy. https://foreignpolicy.com/2022/04/09/russia-putin-propaganda-ukraine-war-crimes-atrocities/

Kravchenko, V. (1947). I Chose Freedom. Garden City Publishing.

Lyons, E. (1937). Assignment in Utopia. Harcourt, Brace and Company. https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.89424/page/n587/mode/2up

Martin, T. (2001). Affirmative Action Empire. Cornell University Press.

McVay, A. & Luciuk, L. Y. (2011). The Holy See and the Holodomor: Documents from the Vatican Secret Archives on the Great Famine of 1932-1933 in Soviet Ukraine. Kashtan Press.

Papakin, H. (n.d.). Blacklists as an Instrument of the Famine-Genocide of 1932-1933 in Ukraine (M. Olynyk, trans.). Key Articles on the Holodomor Translated from Ukrainian into English. Holodomor Research and Education Consortium, 2-3. https://holodomor.ca/resources/further-reading/translated-academic-articles/

Rudnytskyi, O., Levchuk, N., Wolowyna, O., Shevchuk, P., & Kovbasiuk, A. (2015). Demography of a man-made human catastrophe: The case of massive famine in Ukraine 1932-1933. Canadian Studies in Population [ARCHIVES], 42(1-2), 53-80. https://gis.huri.harvard.edu/sites/hwpi.harvard.edu/files/mapa/files/csp-42.pdf?m=1607385802

SCMP Archive. (2014, February 7). Recorded conversation between Asst. Sec. of State Victoria Nuland and Amb. Jeffery Pyatt [video] YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JoW75J5bnnE

Shkandrij, M., & Bertelsen, O. (2013). The Soviet Regime’s National Operations in Ukraine, 1929–1934. Canadian Slavonic Papers, 55(3-4), 417-447.

Snyder, T. (2012). Bloodlands: Europe Between Hitler and Stalin. Basic Books.

Stalin, J. V. (1925). Concerning the National Question in Yugoslavia, Speech Delivered in the Yugoslav Commission of the ECCI, March 30, 1925. Stalin, Works, v7, 71-2. https://www.marxists.org/reference/archive/stalin/works/1925/03/30.htm

Stalin, J. V. (1930). Dizzy with Success: Concerning questions of the collective-farm movement (K. Higham & Mike B., trans.) Pravda. March 2, 1930. Stalin, Works, v12, 197-205. https://www.marxists.org/reference/archive/stalin/works/1930/03/02.htm

United States Congress & Commission on the Ukraine Famine. (1988). Investigation into the Ukrainian Famine, 1932-1933. Report to Congress. U.S. Government Printing Office. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=umn.31951d00831044s&view=1up&seq=1

Viola, L. & Danilov, V. P. (2005). The War Against the Peasantry, 1927-1930: The Tragedy of the Soviet Countryside, Vol. 1. Yale University Press.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed