| By Timothy Holtgrefe March 2023 For several years prior to Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, President Vladimir Putin had devoted much of his time and effort to promoting false narratives and a revisionist history of Ukraine as early as 2005. However, the rhetorical gaslighting and denial of Ukraine’s rich cultural heritage is actually nothing new. In fact for Russian autocrats it is an historical continuity going back several hundred years in an effort to subjugate a race of people. |  Image credit: ForeignPolicy.com |

What is surprising is not that the Russian Empire ‘russified’ their ethnic minorities, as all colonizers have performed similar practices, but that so many of these false narratives continue to persist into today’s political discourse regarding the current war in Ukraine; even in the West. This is part 3 of an HQ exclusive series to investigate Russia’s relentless attack on history. In this episode, we will explore the Soviet Union’s genocidal ‘sovietization’ of Ukrainians through the use of famines, and Putin’s adoption of Lenin’s tactics.

Ukraine’s National Awakening (1880-1918)

To comprehend why Ukrainian peasants were viewed as a threat for both Lenin and Stalin, it is important to understand the context of the Ukrainian national movement during the Russian Revolution.

As both the AustroHungarian, Polish, and Russian Empires discovered throughout their imperialist ventures, the people of the “Ukraine” (meaning borderland in both Russian and Polish) were different from their slavic cousins in Russia and Poland. Although both colonizers sought to undermine the existence of a Ukrainian nation, writers from the late 19th century could not help but notice their unique language and old customs which predated the existence of both their states. Ukrainians still referred to themselves as “Rus” people from the medieval kingdom of Kievan Rus. Not surprising, neither the Poles nor Russians were willing to outwardly concede that their agricultural breadbasket had an independent identity. To effectively absorb Ukraine into the Russian Empire, the Tsarist regime emphasized Ukrainian cultural similarities to Muscovite Russians, even referring to them as Malorussians (meaning ‘little Russians'). Since little to no scholarship of Ukrainian history could be openly acknowledged outside of Austrian held Ruthenia to counter this characterization, the ethnonym “Ukrainian” soon emerged to mean a person who was friendly or actively involved in the

Ukraine’s National Awakening (1880-1918)

To comprehend why Ukrainian peasants were viewed as a threat for both Lenin and Stalin, it is important to understand the context of the Ukrainian national movement during the Russian Revolution.

As both the AustroHungarian, Polish, and Russian Empires discovered throughout their imperialist ventures, the people of the “Ukraine” (meaning borderland in both Russian and Polish) were different from their slavic cousins in Russia and Poland. Although both colonizers sought to undermine the existence of a Ukrainian nation, writers from the late 19th century could not help but notice their unique language and old customs which predated the existence of both their states. Ukrainians still referred to themselves as “Rus” people from the medieval kingdom of Kievan Rus. Not surprising, neither the Poles nor Russians were willing to outwardly concede that their agricultural breadbasket had an independent identity. To effectively absorb Ukraine into the Russian Empire, the Tsarist regime emphasized Ukrainian cultural similarities to Muscovite Russians, even referring to them as Malorussians (meaning ‘little Russians'). Since little to no scholarship of Ukrainian history could be openly acknowledged outside of Austrian held Ruthenia to counter this characterization, the ethnonym “Ukrainian” soon emerged to mean a person who was friendly or actively involved in the

| Ukrainian national movement (Ciancia, 2011). Hence the period from 1880 to 1939 transitioned from Ukrainians self-identifying as Rus (or Ruthenian in the Austrian held territories) to that of “Ukrainians.” In other words, in order to distinguish themselves from their colonizers, Ukrainians had to embrace a new name for themselves and their lands to preserve the uniqueness of their identity. In spite of repressive measures to destroy Ukrainian culture, their language and Cossack traditions were still largely untouched in rural villages. |

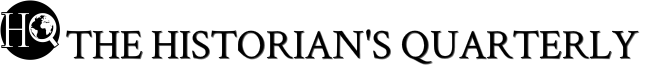

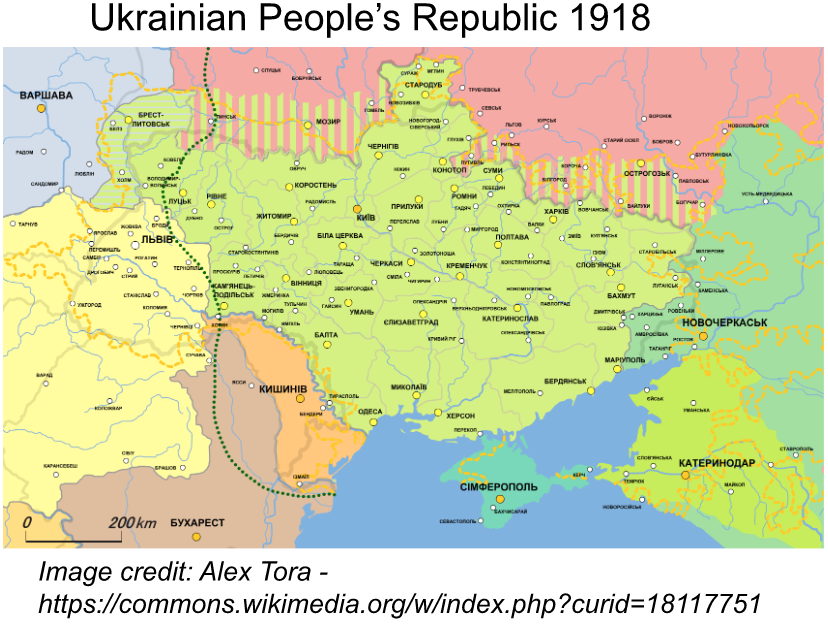

In the aftermath of World War 1 and the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution that followed, Ukrainian nationalists found opportunity in the chaos to separate themselves from Russia. As the Russian Civil War (1917-22) between the Communist Red and Tsarist White armies decimated Russia, Ukraine found itself in a volatile war of independence on many fronts. Concurrently, a series of peasant-led nationalist rebellions broke out all over Ukraine. Its western regions were in the midst of a race war

| with ethnic Poles over the boundaries of the newly formed Polish state that emerged from Woodrow Wilson’s self-determination and Versailles Treaty. After a brief but bloody conflict, the multiethnic territories of western Ukraine were integrated into Poland. In spite of this loss of territory, Ukrainians were finally independent for the first time since Catherine the Great and declared themselves so on January 26, 1918. By February, it won de facto recognition |

from the main European powers, including France, Great Britain, Austria-Hungary, Germany, Bulgaria, Turkey and even Soviet Russia. In December, the United States sent a diplomat to open a consulate in Kyiv (Applebaum, 2017, p.18).

| The Ukrainian Revolution (1917) Blue and yellow flags, and some socialist red, filled every street corner in Kyiv. The newly elected Central Rada (or central council) appointed its first chairman with authority to rule. His name was Mykhailo Hrushevsky, a Ukrainian historian turned political activist. As he approached a podium in front of a crowd of thousands of enthusiastic supporters, he told them to swear “not to rest or cease our labor until we build that free Ukraine.” “We swear!” the crowd shouted back (Bilenky, 2012, p.96-7). The revival of the Ukrainian language was also popular. For the first time, Ukrainian peasants who couldn’t speak Russian suddenly had access to courts and government offices that spoke their language. Inside the Russian empire, not even the Baltic states, which also received independence in 1918, experienced such a national revival similar to Ukraine (Applebaum, 2017, p.15). This revolutionary movement is |

important in understanding why imperial Russia banned Ukrainian books, schools, and culture; and why their repression would be a central goal for both Lenin and Stalin.

The Sovietization of Ukraine

Lenin authorized the first Soviet assault on Ukraine in January 1918, and briefly set up an anti-

The Sovietization of Ukraine

Lenin authorized the first Soviet assault on Ukraine in January 1918, and briefly set up an anti-

| Ukrainian regime the following month. This first attempt to conquer Ukraine ended after a few weeks when the German and Austrian armies arrived declaring they intended to enforce the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk which had already defined Russia’s borders. However, instead of rescuing the democratically elected government, the Germans sought to set up their own puppet state. Subsequently by the middle of 1918, the Ukrainian national movement regrouped under the leadership of Symon Petliura. Unfortunately, as power was continuously changing hands, Petliura never managed to enforce the rule of law; therefore, losing his legitimacy. By 1919 the national movement was in complete chaos, which now seemed to play in favor of the Ukrainian Bolsheviks. As the Bolsheviks eventually obtained absolute power through terror, violence, and vicious propaganda campaigns; few of Ukraine’s Bolsheviks |

spoke Ukrainian. More than half the leadership of the new Soviet Ukraine considered themselves to be Russian (Applebaum, 2017, p.23).

Bolshevik disdain for the very idea of a Ukrainian state predated the revolution. Lenin, Stalin, Trotsky, Piatakov, Zinoviev, Kamenev and Bukharin were all men raised and educated in the Russian empire and consequently only knew Ukraine as “southwest Russia.” Many refused to use the word “Ukraine” at all. (p.23). In addition to their national prejudice, Bolsheviks also had political reasons for disliking Ukrainian independence. Ukraine was still an overwhelmingly peasant nation, which according to Marxist doctrine, was a classless society and therefore could not achieve class consciousness nor enforce the class interests of the proletariat. Additionally, Lenin would continue the tsarist ban on non-Russian languages in schools, such as Ukrainian, since he felt it would create unhelpful divisions in the working class (Borys, 1980, p.30-1).

Sovietization By Propaganda

Propaganda and stereotypes were regularly used to undermine the Ukrainian national movement. The Ukrainian language in particular was regularly attacked as either a “barnyard” language, a vestige of “bourgeois” landowners, or a “counter-revolutionary” language. To any outsider, these labels may seem contradictory and hard to follow since they depended on the radically shifting political climate. Christian Rakovsky, first leader of the Ukrainian Council of People’s Commissars in 1921, discouraged the use of the Ukrainian language as he declared it signaled a return to the “rule of the Ukrainian petit-bourgeois intelligentsia and the Ukrainian kulaks” (Martin, 2001, p.78). His deputy, Dmytro Lebed, argued Ukrainian was reactionary because it was an inferior language of the village, whereas Russian was the superior language of the city. In an essay outlining his “Theory of the Two Cultures,” Lebed said that they should all study Russian, in order to help them eventually merge with the Russian proletariat (p.79). Since the peasantry was undeniably proletarian in origin, their overwhelming rejection of Soviet rule was an obvious contradiction that needed a rationale. It was

Bolshevik disdain for the very idea of a Ukrainian state predated the revolution. Lenin, Stalin, Trotsky, Piatakov, Zinoviev, Kamenev and Bukharin were all men raised and educated in the Russian empire and consequently only knew Ukraine as “southwest Russia.” Many refused to use the word “Ukraine” at all. (p.23). In addition to their national prejudice, Bolsheviks also had political reasons for disliking Ukrainian independence. Ukraine was still an overwhelmingly peasant nation, which according to Marxist doctrine, was a classless society and therefore could not achieve class consciousness nor enforce the class interests of the proletariat. Additionally, Lenin would continue the tsarist ban on non-Russian languages in schools, such as Ukrainian, since he felt it would create unhelpful divisions in the working class (Borys, 1980, p.30-1).

Sovietization By Propaganda

Propaganda and stereotypes were regularly used to undermine the Ukrainian national movement. The Ukrainian language in particular was regularly attacked as either a “barnyard” language, a vestige of “bourgeois” landowners, or a “counter-revolutionary” language. To any outsider, these labels may seem contradictory and hard to follow since they depended on the radically shifting political climate. Christian Rakovsky, first leader of the Ukrainian Council of People’s Commissars in 1921, discouraged the use of the Ukrainian language as he declared it signaled a return to the “rule of the Ukrainian petit-bourgeois intelligentsia and the Ukrainian kulaks” (Martin, 2001, p.78). His deputy, Dmytro Lebed, argued Ukrainian was reactionary because it was an inferior language of the village, whereas Russian was the superior language of the city. In an essay outlining his “Theory of the Two Cultures,” Lebed said that they should all study Russian, in order to help them eventually merge with the Russian proletariat (p.79). Since the peasantry was undeniably proletarian in origin, their overwhelming rejection of Soviet rule was an obvious contradiction that needed a rationale. It was

| Stalin himself who began a propaganda blitz in a series of essays published in Pravda, November 1917. In response to the formation of the Ukrainian state and laying out its national borders, he claimed that only “Big landowners” and the “Russian bourgeoisie” support an independent Ukraine. Continuing his lie, he added, “all Ukrainian workers and the poorest |

section of the peasantry” opposed the Central Rada, which was hardly true either. (Borys, 1980, p.174-5). As with the previous tsarist regime, the mere existence of Ukraine and Ukrainians was a threat to the state-building mythology of the Soviet Union (see Part 1). Class solidarity, not national solidarity under Moscow, was supposed to guide the way.

Much as they would one day use history, journalism, and politics to cover up the famine and to twist the facts of Ukrainian history, Soviet propagandists also sought to use the pogroms to discredit the Ukrainian national movement. Between 1918-20, combatants on all sides (White, Directory, Polish, and Bolshevik) murdered at least 50,000 Jews in 1,300 pogroms across Ukraine. Although evidence has been long cherry-picked by authors seeking to prove a case for or against the Bolsheviks, the White Army, the Poles, or the Central Rada; for decades Soviet historians in particular characterized Petliura as little more than an anti-semite and denied the Bolshevik role in the pograms. Instead, they linked the Ukrainian national movement to looting, killing, and above all pogroms. Great efforts were made to gather “testimony” against Petliura and the generals who were associated with him, and to publish it in different languages (Applebaum, 2017, p.63). However, Petliura is not known to have used anti-semetic language and deliberately included Jews in the Central Rada to discourage anti-semetism “Because Christ commands it, we urge everyone to help the Jewish sufferers.” (Abramson, 2018, p.157). In truth, the violence was greatest in areas that were not under any political control at all. Nonetheless, decades of portraying Ukrainian nationalists as anti-semites would conveniently reemerge well into Putin’s contemporary propaganda machine to soften international support for Ukrainian sovereignty.

Much as they would one day use history, journalism, and politics to cover up the famine and to twist the facts of Ukrainian history, Soviet propagandists also sought to use the pogroms to discredit the Ukrainian national movement. Between 1918-20, combatants on all sides (White, Directory, Polish, and Bolshevik) murdered at least 50,000 Jews in 1,300 pogroms across Ukraine. Although evidence has been long cherry-picked by authors seeking to prove a case for or against the Bolsheviks, the White Army, the Poles, or the Central Rada; for decades Soviet historians in particular characterized Petliura as little more than an anti-semite and denied the Bolshevik role in the pograms. Instead, they linked the Ukrainian national movement to looting, killing, and above all pogroms. Great efforts were made to gather “testimony” against Petliura and the generals who were associated with him, and to publish it in different languages (Applebaum, 2017, p.63). However, Petliura is not known to have used anti-semetic language and deliberately included Jews in the Central Rada to discourage anti-semetism “Because Christ commands it, we urge everyone to help the Jewish sufferers.” (Abramson, 2018, p.157). In truth, the violence was greatest in areas that were not under any political control at all. Nonetheless, decades of portraying Ukrainian nationalists as anti-semites would conveniently reemerge well into Putin’s contemporary propaganda machine to soften international support for Ukrainian sovereignty.

Sovietization By Russification

Bolshevik occupation brought with it not only communist ideology, but also a clearly Russian agenda that resulted in genocide. General Mykhail Muraviev, the commanding officer, declared he was bringing back Russian rule from the “far North,” and ordered the immediate execution of suspected nationalists. His men shot anyone heard speaking Ukrainian in public and destroyed any evidence of Ukrainian rule including the Ukrainian street signs that had replaced Russian streets shortly after the revolution He also deliberately targeted libraries and their collections of ancient artifacts (Borys, 1980, p.79). Lenin, using the methods of what would be called “hybrid warfare,” ordered his red army to enter Ukraine in disguise. They were to hide the fact that they were a Russian force fighting for a unified Bolshevik Russia. Instead, they called themselves a “Soviet Ukrainian liberation movement,” precisely in order to confuse nationalists. As Borys (1980) cites Lenin in a telegram to the Red Army commander on the ground, Lenin explained:

With the advance of our troops to the west and into Ukraine, regional provisional Soviet governments are created whose task it is to strengthen the local Soviets…taking away from the chauvinists of Ukraine…the possibility of regarding the advance of our detachments as occupation and creates a favorable atmosphere for a further advance of our troops (p. 205-6).

At no point in 1918, or later, did Lenin or Stalin believe that any Soviet-Ukrainian state would ever enjoy full sovereignty. Using methods Vladimir Putin would imitate in 2014, the Red Army covertly invaded Ukraine, denied their assault was taking place, while simultaneously fainting negotiations with Petiliura. The Bolshevik People’s Commissar for Foreign Affairs, blandly replied that Moscow had nothing to do with the troops moving onto Ukrainian soil. He blamed the military action of the territory on “the army of the Ukrainian Soviet government” which was in actual fact the Red Army (p.221). In spite of these efforts, Moscow never controlled the whole area of what would become the Ukrainian Republic. Although they were able to capture cities, the villagers often remained under the sway of local partisan leaders.

Bolshevik occupation brought with it not only communist ideology, but also a clearly Russian agenda that resulted in genocide. General Mykhail Muraviev, the commanding officer, declared he was bringing back Russian rule from the “far North,” and ordered the immediate execution of suspected nationalists. His men shot anyone heard speaking Ukrainian in public and destroyed any evidence of Ukrainian rule including the Ukrainian street signs that had replaced Russian streets shortly after the revolution He also deliberately targeted libraries and their collections of ancient artifacts (Borys, 1980, p.79). Lenin, using the methods of what would be called “hybrid warfare,” ordered his red army to enter Ukraine in disguise. They were to hide the fact that they were a Russian force fighting for a unified Bolshevik Russia. Instead, they called themselves a “Soviet Ukrainian liberation movement,” precisely in order to confuse nationalists. As Borys (1980) cites Lenin in a telegram to the Red Army commander on the ground, Lenin explained:

With the advance of our troops to the west and into Ukraine, regional provisional Soviet governments are created whose task it is to strengthen the local Soviets…taking away from the chauvinists of Ukraine…the possibility of regarding the advance of our detachments as occupation and creates a favorable atmosphere for a further advance of our troops (p. 205-6).

At no point in 1918, or later, did Lenin or Stalin believe that any Soviet-Ukrainian state would ever enjoy full sovereignty. Using methods Vladimir Putin would imitate in 2014, the Red Army covertly invaded Ukraine, denied their assault was taking place, while simultaneously fainting negotiations with Petiliura. The Bolshevik People’s Commissar for Foreign Affairs, blandly replied that Moscow had nothing to do with the troops moving onto Ukrainian soil. He blamed the military action of the territory on “the army of the Ukrainian Soviet government” which was in actual fact the Red Army (p.221). In spite of these efforts, Moscow never controlled the whole area of what would become the Ukrainian Republic. Although they were able to capture cities, the villagers often remained under the sway of local partisan leaders.

| To further undermine Ukrainian statehood, Stalin had local Bolsheviks try to establish so-called independent “Soviet republics” in Donetsk, Kryvyi Rih, Odessa, Tavriia, and the Don province. The Bolsheviks also attempted to stage a coup in Kyiv; after that failed, they created an “alternative” executive committee in Kharkiv, which they would later turn into the capital, even though only a handful of these so-called Ukrainian Bolsheviks actually spoke Ukrainian (p.183). |

Defining Peasants as the Enemy

As Leon Trotsky onced observed, Ukraine’s major cities were colonial-controlled islands of Russian, Polish, or Jewish culture in a sea of Ukrainian peasants. (Applebaum, 2017, p.7). Joseph Stalin's views evolved to blame peasants for the existence of national movements inside the USSR: “The peasant question is the basis, the quintessence, of the national question. That explains the movement, that there is no powerful national movement without the peasant army…” (Stalin, 1925). These views reflected Stalin’s position on the national movement in Ukraine. To destroy the national movement, the USSR would have to destroy the peasantry. After the Bolshevik revolution, Stalin’s initial position in the party was to negotiate with all the non-Russian nations and peoples who had belonged to the Russian empire–and more importantly, convincing, or forcing, them to submit to Soviet rule. In his dealings with Ukraine, he had two priorities: 1) undermine the national movement and 2) to get hold of Ukrainian grain. It was with this task in mind he began his propaganda blitz against Ukrainian land owners. (Applebaum, 2017, p.27).

The People’s Commissar of Food Collection in Ukraine, Alexander Shlikhter, chose a more sophisticated form of violence. He created a new class system in the villages and then encouraged antagonism between them. With his rigid Marxist training and hierarchical way of seeing the world, Shlikhter would define three categories of peasant: kulaks, or wealthy peasants; seredniaks, or middle peasants; and bedniaks, or poor peasants (p.42). Although Bolsheviks would always struggle to

As Leon Trotsky onced observed, Ukraine’s major cities were colonial-controlled islands of Russian, Polish, or Jewish culture in a sea of Ukrainian peasants. (Applebaum, 2017, p.7). Joseph Stalin's views evolved to blame peasants for the existence of national movements inside the USSR: “The peasant question is the basis, the quintessence, of the national question. That explains the movement, that there is no powerful national movement without the peasant army…” (Stalin, 1925). These views reflected Stalin’s position on the national movement in Ukraine. To destroy the national movement, the USSR would have to destroy the peasantry. After the Bolshevik revolution, Stalin’s initial position in the party was to negotiate with all the non-Russian nations and peoples who had belonged to the Russian empire–and more importantly, convincing, or forcing, them to submit to Soviet rule. In his dealings with Ukraine, he had two priorities: 1) undermine the national movement and 2) to get hold of Ukrainian grain. It was with this task in mind he began his propaganda blitz against Ukrainian land owners. (Applebaum, 2017, p.27).

The People’s Commissar of Food Collection in Ukraine, Alexander Shlikhter, chose a more sophisticated form of violence. He created a new class system in the villages and then encouraged antagonism between them. With his rigid Marxist training and hierarchical way of seeing the world, Shlikhter would define three categories of peasant: kulaks, or wealthy peasants; seredniaks, or middle peasants; and bedniaks, or poor peasants (p.42). Although Bolsheviks would always struggle to

| identify who was a kulak, it basically came to mean whoever was the most successful private grain producer. Later it would simply be whoever Stalin said was a Kulak. In other words, Bulshiviks actively sought to deepen divisions inside villages, to use anger and resentment to divide and conquer Ukrainian peasants to further their cause. Furthermore, when Bolshevik policies led to famine in the new Soviet empire, it would be peasants in Ukraine in particular who were scapegoated. |

Lenin’s Man-Made Famine (1918-22)

In many ways, the smaller 1921 famine under Lenin was a “dress rehearsal” for the larger 1932-3 famine under Stalin, known as Holodomor. The Bolshevik obsession with food was always political. For the Russian Empire, its struggle with food supplies during the First World War is largely credited for its downfall. Both before, during, and after the revolution; all sides realized that constant shortages made food supplies a significant political tool. Whoever had bread had followers, soldiers, and loyal friends. Whoever could not feed their people rapidly lost support. (Applebaum, 2017, p.32-33). Within this context, the Bolsheviks assumed that the exploitation of Ukraine was necessary in order to maintain control of Russia. Tormented with food shortages, the Bolsheviks were already seizing Ukrainian grain by gunpoint as early as 1918, as Ukrainians were forced to sell their crop to the state at prices dictated by the state. (Holquist, 2002, p.96). Rather than sell their crops below market value, many peasants withheld their grain and waited for prices to rise again before selling in local bazaars or on the black market for what seemed worthy of their hard labors, thus creating a food shortage. Having violated the basic economic ‘law of supply,’ Soviet leadership was surprised by the hunger and shortages that their “confiscate and redistribute” system had created. (Applbaum, 2017, p.36). However, the Bolsheviks never blamed any failures on their own policies and began to scapegoat the peasantry who Lenin accused of holding back surplus to sabotage the Soviet Union.

In the decade preceding Holodomor, the groundwork for mass genocide was already being laid down by the Soviets: the need for scapegoats of the failed grain policy and the hateful, anti-Ukrainian rhetoric which became a standard part of Bolshevik language in occupied Kyiv. As one occupier wrote, “It wasn’t difficult to raise the morale of this army. All one had to say was that our ‘brothers’ are starving because of the Ukrainian-Khokhly [derogatory term for Ukrainians]. This is how our comrades lit the fires of hatred for Ukrainians.” (p.39). More to the point, the fate of the Soviet Union rested in the hands of Ukraine’s private landowning peasants who produced more grain with greater efficiency than Lenin’s failed collective farms. Not only did this mere fact threaten basic Marxist ideology, these peasants spoke almost exclusively Ukrainian and were a stronghold for Ukrainian nationalism. They prided themselves on their Cossack traditions of self-reliance and independence through farming and refused to sacrifice this freedom to impoverish themselves by selling their grain below market value. Although the peasants would have happily bartered their grain for clothing and tools, Russia was barely producing any manufactured goods and had nothing to offer them. For Lenin, force was the only solution.

In many ways, the smaller 1921 famine under Lenin was a “dress rehearsal” for the larger 1932-3 famine under Stalin, known as Holodomor. The Bolshevik obsession with food was always political. For the Russian Empire, its struggle with food supplies during the First World War is largely credited for its downfall. Both before, during, and after the revolution; all sides realized that constant shortages made food supplies a significant political tool. Whoever had bread had followers, soldiers, and loyal friends. Whoever could not feed their people rapidly lost support. (Applebaum, 2017, p.32-33). Within this context, the Bolsheviks assumed that the exploitation of Ukraine was necessary in order to maintain control of Russia. Tormented with food shortages, the Bolsheviks were already seizing Ukrainian grain by gunpoint as early as 1918, as Ukrainians were forced to sell their crop to the state at prices dictated by the state. (Holquist, 2002, p.96). Rather than sell their crops below market value, many peasants withheld their grain and waited for prices to rise again before selling in local bazaars or on the black market for what seemed worthy of their hard labors, thus creating a food shortage. Having violated the basic economic ‘law of supply,’ Soviet leadership was surprised by the hunger and shortages that their “confiscate and redistribute” system had created. (Applbaum, 2017, p.36). However, the Bolsheviks never blamed any failures on their own policies and began to scapegoat the peasantry who Lenin accused of holding back surplus to sabotage the Soviet Union.

In the decade preceding Holodomor, the groundwork for mass genocide was already being laid down by the Soviets: the need for scapegoats of the failed grain policy and the hateful, anti-Ukrainian rhetoric which became a standard part of Bolshevik language in occupied Kyiv. As one occupier wrote, “It wasn’t difficult to raise the morale of this army. All one had to say was that our ‘brothers’ are starving because of the Ukrainian-Khokhly [derogatory term for Ukrainians]. This is how our comrades lit the fires of hatred for Ukrainians.” (p.39). More to the point, the fate of the Soviet Union rested in the hands of Ukraine’s private landowning peasants who produced more grain with greater efficiency than Lenin’s failed collective farms. Not only did this mere fact threaten basic Marxist ideology, these peasants spoke almost exclusively Ukrainian and were a stronghold for Ukrainian nationalism. They prided themselves on their Cossack traditions of self-reliance and independence through farming and refused to sacrifice this freedom to impoverish themselves by selling their grain below market value. Although the peasants would have happily bartered their grain for clothing and tools, Russia was barely producing any manufactured goods and had nothing to offer them. For Lenin, force was the only solution.

| However, in response to these unpopular grain confiscations, Lenin’s plan had backfired. Many Russian and Ukrainian speaking Cossacks in the Don and Kuban regions viewed the attack on Kulaks as “deCossackization.” These Cossacks, though initially supporters of the Red Army, began deserting in droves. In their wake, the largest and most violent peasant uprising in modern European history exploded across the countryside. Unfortunately, this offered no |

advantage to the White Army that continued to alienate Ukrainians by still referring to them as “Little Russians” (Palij, 1976, p.187). The Bolsheviks responded to the uprising, referring to it as a “kulak uprising” led by “kulak traitors.” The word Kulak had already acquired a broader meaning, well beyond “rich peasant” to anyone who stored their excess grain, to finally anyone who opposed Soviet rule. (Applebaum, 2017, p.53).

Historically, both Russian and Ukrainian peasants had survived periodic bad weather and frequent droughts through the careful preservation and storage of surplus grain. However, in the Spring of 1921, there was no surplus grain; it had all been confiscated. (p.72). The politics and policies of the Bolsheviks had left the economy completely

Historically, both Russian and Ukrainian peasants had survived periodic bad weather and frequent droughts through the careful preservation and storage of surplus grain. However, in the Spring of 1921, there was no surplus grain; it had all been confiscated. (p.72). The politics and policies of the Bolsheviks had left the economy completely

| dysfunctional. Agricultural provinces in imperial Russia had annually produced 20 million tonnes of grain before the revolution. In 1920 they produced just 8.4 million tonnes, and by 1921 they were down to 2.9 million tonnes. Nearly 25 million people were going hungry throughout the Soviet Union. (p.73). |

Trotsky, in a letter to his colleagues, explained that peace would be difficult to enforce in Ukraine. For although the Red Army had won a military victory, there had been no ideological revolution in Ukraine: “Soviet power in Ukraine has held its ground up to now (and it has not held it well) chiefly by the authority of Moscow, by the Great Russian communists and by the Russian Red Army.” (Borys, 1980, p.294). The implication was clear: force, not persuasion, had finally pacified Ukraine. However, the ideological threat remained. Lenin echoed Trotsky’s warning in a letter to Vyacheslav Molotov: “We must teach these people a lesson right now, so that they will not even dare to think of resistance in the coming decade” (Lenin, 1922, p.152).

Famine as a Weapon?

This first Soviet famine did differ from the famine that was to follow a decade later: in 1921 mass hunger was not kept secret, the regime tried to help the starving, and international appeals for aid followed. As it would a decade later, the authorities’ reaction to the famine also differed between Russia and Ukraine. The priority of the famine committees were instructed to direct any surplus Ukrainian grain to the starving Russian provinces of Tsaritsyn, Uralsk, Saratoc, and Simbirsk; not to the starving people of southern Ukraine. Lenin gave the grain collection teams a clear order: “In every village take between 15 and 20 hostages, and, in case of unmet quotas, put them all up against the wall.” If that tactic failed, hostages were to be shot as “enemies of the state” (cited by Applebaum, 2017, p.76). Initially, the authorities in Moscow did not tell the international relief workers and Americans about the food shortages in Ukraine at all. They were told by Soviet authorities that they could not operate in Ukraine because, unlike Russia, it did not have an agreement with the American Relief Administration, (ARA). Skrypnyk responded that Ukraine was a sovereign state and not part of Russia. Given that Ukraine was at that time contributing to the relief of the Soviet famine, was subject to Soviet laws and confiscatory Soviet agricultural policy, Skrypnyk’s insistence on Ukrainian sovereignty in the matter of famine relief was absurd (p.77).

Famine as a Weapon?

This first Soviet famine did differ from the famine that was to follow a decade later: in 1921 mass hunger was not kept secret, the regime tried to help the starving, and international appeals for aid followed. As it would a decade later, the authorities’ reaction to the famine also differed between Russia and Ukraine. The priority of the famine committees were instructed to direct any surplus Ukrainian grain to the starving Russian provinces of Tsaritsyn, Uralsk, Saratoc, and Simbirsk; not to the starving people of southern Ukraine. Lenin gave the grain collection teams a clear order: “In every village take between 15 and 20 hostages, and, in case of unmet quotas, put them all up against the wall.” If that tactic failed, hostages were to be shot as “enemies of the state” (cited by Applebaum, 2017, p.76). Initially, the authorities in Moscow did not tell the international relief workers and Americans about the food shortages in Ukraine at all. They were told by Soviet authorities that they could not operate in Ukraine because, unlike Russia, it did not have an agreement with the American Relief Administration, (ARA). Skrypnyk responded that Ukraine was a sovereign state and not part of Russia. Given that Ukraine was at that time contributing to the relief of the Soviet famine, was subject to Soviet laws and confiscatory Soviet agricultural policy, Skrypnyk’s insistence on Ukrainian sovereignty in the matter of famine relief was absurd (p.77).

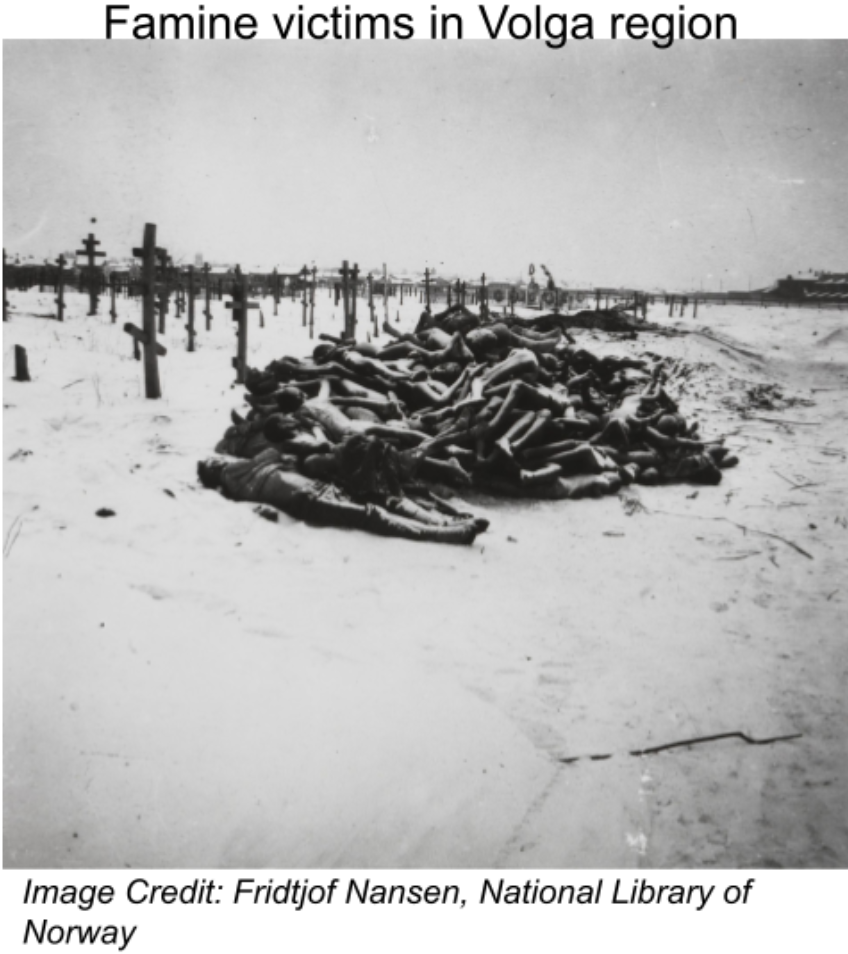

| Finally in 1922 the Ukrainian Politburo agreed to work with the ARA. By the end of 1923 the crisis seemed to be under control, but tens of thousands of unnecessary deaths resulted from the delays in the delivery of aid. Most ARA members believed at the time that the initial Soviet opposition to their relief program in Ukraine was politically inspired. Indeed the worst-hit regions in the whole of the USSR, had also been Cossack strongholds and Ukrainian |

speaking peasants. One American relief worker noted that perhaps Soviet authorities were “willing to let the Ukraine suffer, rather than take the chance of new uprisings which might follow foreign

| contact.” (cited by Applebaum, 2017, p.79). Today more and more historians support the thesis that Soviet authorities actually used the famine instrumentally, as they would in 1932, to put an end to the Ukrainian peasant rebellion. However, without concrete proof of a premeditated plan, Lenin’s intentional genocide by famine will continue to be debated. In any case, the grain requisition system did break up communities, severed relationships, and forced peasants to leave home in search of food. According to Applebaum 2017, “if Moscow had indeed been using its agricultural policy to put |

down rebellion, it could hardly have done so more efficiently” (p.79). Starvation weakened and demoralized those who remained, forcing them to abandon the armed struggle. Over the course of three years, 33.5 million people were affected by famine or food shortages—26 million in Russia, 7.5 million in Ukraine. Though the exact death rates are difficult to determine since no one was keeping track, best guesses estimate between 250,000 and 500,000 people were starved to death in southern Ukraine, the hardest-hit region. In the USSR as a whole the ARA estimated that 2 million people had died. A Soviet publication produced soon after the famine concluded that 5 million had died. (Patenaude, 2002, p.197-8).

Whether elements of the 1919-22 famine were deliberate or not, the Soviets noticed it was effective in destroying the peasant rebellions and by 1922 the Bolsheviks knew that they were unpopular in rural farmlands, and especially the Ukrainian countryside. Their rejection of everything that looked or sounded “Ukrainian” had helped keep nationalist, anti-Bolshevik anger alive in Ukraine.

Conclusion

Although Lenin cannot be linked to a premeditated plan to deliberately starve the Soviet peasantry, it is clear that once the famine had begun the conditions were deliberately worsened in Ukrainian speaking areas both within Soviet Ukraine and in the Kuban region. Every step of the way, orders were given that disproportionately impacted Ukrainians: 1) the unequal distribution of their confiscated grain in favor of Russian provinces, 2) their refusal to allow international aid relief to enter Ukraine, and 3) the Bolshevik propaganda blitz towards ethnic Ukrainians that led to outright hatred of anything Ukrainian—-resulting in mass killings. As with all genocides, the starvation of Ukrainians began with an intense propaganda effort crafted by the Soviet Union that far exceeded tsarist Russia in undermining Ukrainian statehood. This architecture of lies was so religiously constructed by the Bolsheviks that it left a convenient foundation of stereotypes and hatreds for Moscow’s newest autocrat to once again carry on the very old tradition of Russian genocide towards Ukrainians. Today’s propaganda has all the familiar, contradictory labels for Ukrainians with the digital tools to target specific audiences. As historian Timothy Schneider often notices, Ukraianians are simultaneously gay, Jewish, and Nazis: “It is ridiculous to treat Zelensky as part of both a world Jewish conspiracy and a Nazi plot, but Russian propaganda routinely makes both claims” (Schneider, 2022). The Kremlin still cherry-picks historical facts to paint Ukrainian nationalists as anti-semites while simultaneously plagiarizing both Lenin and Stalin’s playbook of covert invasions disguised as Ukrainian partisans. As with the Bolsheviks, these incursions were followed by breaking up territories into mini-republics and weaponizing Ukrainian grain. There is nothing clever about Putin’s tactics. In retrospect, his invasions of Crimea and the Donbass in 2014 were both unoriginal as they were gaslighted. Perhaps the only crime appropriate to this level of injustice is our own historical ignorance of Ukraine in the west, which only serves Russian disinformation efforts to weaken our resolve and erase these resilient people from existence.

How did Stalin use the lessons of the 1918-22 famine to accelerate his own genocide of Ukraine in 1932-34? What is Holodomor and why is it still widely unknown in the west? Standby for the second half of genocide by famine in Part IV as The HQ continues its exclusive series on Russia’s revisionist history and gaslighting of Ukraine.

Whether elements of the 1919-22 famine were deliberate or not, the Soviets noticed it was effective in destroying the peasant rebellions and by 1922 the Bolsheviks knew that they were unpopular in rural farmlands, and especially the Ukrainian countryside. Their rejection of everything that looked or sounded “Ukrainian” had helped keep nationalist, anti-Bolshevik anger alive in Ukraine.

Conclusion

Although Lenin cannot be linked to a premeditated plan to deliberately starve the Soviet peasantry, it is clear that once the famine had begun the conditions were deliberately worsened in Ukrainian speaking areas both within Soviet Ukraine and in the Kuban region. Every step of the way, orders were given that disproportionately impacted Ukrainians: 1) the unequal distribution of their confiscated grain in favor of Russian provinces, 2) their refusal to allow international aid relief to enter Ukraine, and 3) the Bolshevik propaganda blitz towards ethnic Ukrainians that led to outright hatred of anything Ukrainian—-resulting in mass killings. As with all genocides, the starvation of Ukrainians began with an intense propaganda effort crafted by the Soviet Union that far exceeded tsarist Russia in undermining Ukrainian statehood. This architecture of lies was so religiously constructed by the Bolsheviks that it left a convenient foundation of stereotypes and hatreds for Moscow’s newest autocrat to once again carry on the very old tradition of Russian genocide towards Ukrainians. Today’s propaganda has all the familiar, contradictory labels for Ukrainians with the digital tools to target specific audiences. As historian Timothy Schneider often notices, Ukraianians are simultaneously gay, Jewish, and Nazis: “It is ridiculous to treat Zelensky as part of both a world Jewish conspiracy and a Nazi plot, but Russian propaganda routinely makes both claims” (Schneider, 2022). The Kremlin still cherry-picks historical facts to paint Ukrainian nationalists as anti-semites while simultaneously plagiarizing both Lenin and Stalin’s playbook of covert invasions disguised as Ukrainian partisans. As with the Bolsheviks, these incursions were followed by breaking up territories into mini-republics and weaponizing Ukrainian grain. There is nothing clever about Putin’s tactics. In retrospect, his invasions of Crimea and the Donbass in 2014 were both unoriginal as they were gaslighted. Perhaps the only crime appropriate to this level of injustice is our own historical ignorance of Ukraine in the west, which only serves Russian disinformation efforts to weaken our resolve and erase these resilient people from existence.

How did Stalin use the lessons of the 1918-22 famine to accelerate his own genocide of Ukraine in 1932-34? What is Holodomor and why is it still widely unknown in the west? Standby for the second half of genocide by famine in Part IV as The HQ continues its exclusive series on Russia’s revisionist history and gaslighting of Ukraine.

References

Abramson, H. (2018). A Prayer for the Government: Ukrainians and Jews in Revolutionary Times, 1917-1920, Revised Edition. United Kingdom: Lulu.com.

Applebaum, A. (2017). Red Famine: Stalin’s war on Ukraine. Anchor Books.

Bilenky, S. (2012). Romantic Nationalism in Eastern Europe: Russian, Polish, and Ukrainian Political Imaginations. Redwood City: Stanford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1515/9780804780568

Borys, J. (1980). The Sovietization of Ukraine, 1917-1923: The Communist Doctrine and Practice of National Self-Determination. Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Study Press; Revised edition.

Ciancia, K. C. (2011). POLAND’S WILD EAST: IMAGINED LANDSCAPES AND EVERYDAY LIFE IN THE VOLHYNIAN BORDERLANDS, 1918-1939: Doctoral Dissertation. Stanford University. https://purl.stanford.edu/sz204nw1638

Holquist, P. (2002). Making War, Forging Revolution: Russia's continuum of crisis, 1914-1921. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Lenin, V. I. (edited 1996). The Unknown Lenin: From the Secret Archive. United Kingdom: Yale University Press.

Martin, T. D. (2001). The Affirmative Action Empire: nations and nationalism in the Soviet Union, 1923-1939. Cornell University Press.

Palij, M. (1976). The Anarchism of Nestor Makhno, 1918-1921: An Aspect of the Ukrainian Revolution. University of Washington Press. http://www.ditext.com/palij/makhno.html

Patenaude, B. M. (2002). The Big Show in Bololand: The American Relief Expedition to Soviet Russia in the Famine of 1921. United Kingdom: Stanford University Press.

Snyder, T. (2022). Ukraine Holds the Future. Foreign Affairs, September 5. https://www.foreignaffairs.com/ukraine/ukraine-war-democracy-nihilism-timothy-snyder.

Stalin, J. V. (1925). Concerning the National Question in Yugoslavia, Speech Delivered in the Yugoslav Commission of the ECCI, March 30, 1925. Stalin, Works, v7, 71-2. https://www.marxists.org/reference/archive/stalin/works/1925/03/30.htm

RSS Feed

RSS Feed