What is surprising is not that the Russian Empire ‘russified’ their ethnic minorities, as all colonizers have performed similar practices, but that so many of these false narratives continue to persist into today’s political discourse regarding the current war in Ukraine; even in the West. This is part 1 of an HQ exclusive series to investigate Russia’s relentless attack on history. In this episode, we will explore the mythology of Russia’s historical origin known as the Third Rome Theory as the historical motive for Russian gaslighting.

The Third Rome Theory

Perhaps one of the more egregious historical and cultural inaccuracies peddled by the current autocrat of Russia is that Ukraine never existed or has no unique identity outside Russian history. This falsehood serves several purposes for the Kremlin: 1) it has historically legitimized Russia’s own mythology in the Third Rome Theory amongst both traditional Russian imperialists and the ‘Russian World’ ideology by modern nationalists, and 2) it delegitimizes Ukrainian statehood which stands in the way of Russian attempts to control its warm-water ports and vast natural resources. What is the Third Rome Theory? How has it necessitated continual cultural genocide of Ukraine?

National Origins

The Third Rome Theory

Perhaps one of the more egregious historical and cultural inaccuracies peddled by the current autocrat of Russia is that Ukraine never existed or has no unique identity outside Russian history. This falsehood serves several purposes for the Kremlin: 1) it has historically legitimized Russia’s own mythology in the Third Rome Theory amongst both traditional Russian imperialists and the ‘Russian World’ ideology by modern nationalists, and 2) it delegitimizes Ukrainian statehood which stands in the way of Russian attempts to control its warm-water ports and vast natural resources. What is the Third Rome Theory? How has it necessitated continual cultural genocide of Ukraine?

National Origins

| Russia, Belarus, and Ukraine all share the same cultural heritage from the kingdom of Kievan Rus (882-1240 AD). After the first Slavic groups migrated out of central Asia into eastern Europe, the eastern Slavic tribes integrated with Scandinavian settlers along the Dnieper River to form the Kingdom of Kievan Rus. Its capital was Kyiv, the current capital of Ukraine. Although this kingdom has both cultural and religious foundations for all eastern slavs, Russian imperialists prefer to see themselves as the sole political and religious inheritors of this kingdom since it was the birthplace of Christian Orthodoxy for the |

slavic world. As part of an effort to unite all slavic lands under their banner (whether willingly or by conquest) this genesis has been emphasized to claim an even greater imperial mandate from the ancient Roman Empire via the kingdom’s links to Constantinople.

Although the diplomatic ties between Kievan Rus and the Byzantine Empire factored into Vladimir the Great’s conversion to Christianity in 988 AD, political ties to Byzantium have been exaggerated by Russian Tsars to present Kievan Rus as the theocratic continuation of the original Roman Empire by virtue of Constantinople after the fall of the Western empire in 476 AD. After Constantinople’s fall in 1453 to the Ottoman Turks, Russia’s imperial historians have crafted a mythology framing Moscow as the new successor to Rome after Constantinople: hence the Third Rome. However, in order for this loose “Third Rome Theory” to hold weight, Russia had to first present itself as the political inheritance of the Kievan Rus, and this is why Ukraine’s mere existence as a separate state is an ideological threat to Russian nationalist mythology and Russia’s pan-slavism, or ‘Russian World’. This is where the revisionist history for Ukraine truly all begins.

Why Moscow is Not the Political Continuity of Kievan Rus

In his 2021 essay, Putin referred to Russians and Ukrainians as “one people” and called whatever divisions that may exist “artificial.” Putting the obvious cultural differences and lack of source citations aside, the extent of his distortion requires a skewed narrative of historical facts rooted in centuries of state propaganda. How the Rus lands later evolved into their separate identities after the fall of Kievan Rus is essential to halting the spread of these lies and to quarantine the cultural genocide currently taking place.

As Kievan Rus began to disintegrate into political disunity over successional disputes, the kingdom partitioned into several princely states vying to retake Kyiv in order to claim the symbolic right to rule all the Rus lands. These rival kingdoms included

Although the diplomatic ties between Kievan Rus and the Byzantine Empire factored into Vladimir the Great’s conversion to Christianity in 988 AD, political ties to Byzantium have been exaggerated by Russian Tsars to present Kievan Rus as the theocratic continuation of the original Roman Empire by virtue of Constantinople after the fall of the Western empire in 476 AD. After Constantinople’s fall in 1453 to the Ottoman Turks, Russia’s imperial historians have crafted a mythology framing Moscow as the new successor to Rome after Constantinople: hence the Third Rome. However, in order for this loose “Third Rome Theory” to hold weight, Russia had to first present itself as the political inheritance of the Kievan Rus, and this is why Ukraine’s mere existence as a separate state is an ideological threat to Russian nationalist mythology and Russia’s pan-slavism, or ‘Russian World’. This is where the revisionist history for Ukraine truly all begins.

Why Moscow is Not the Political Continuity of Kievan Rus

In his 2021 essay, Putin referred to Russians and Ukrainians as “one people” and called whatever divisions that may exist “artificial.” Putting the obvious cultural differences and lack of source citations aside, the extent of his distortion requires a skewed narrative of historical facts rooted in centuries of state propaganda. How the Rus lands later evolved into their separate identities after the fall of Kievan Rus is essential to halting the spread of these lies and to quarantine the cultural genocide currently taking place.

As Kievan Rus began to disintegrate into political disunity over successional disputes, the kingdom partitioned into several princely states vying to retake Kyiv in order to claim the symbolic right to rule all the Rus lands. These rival kingdoms included

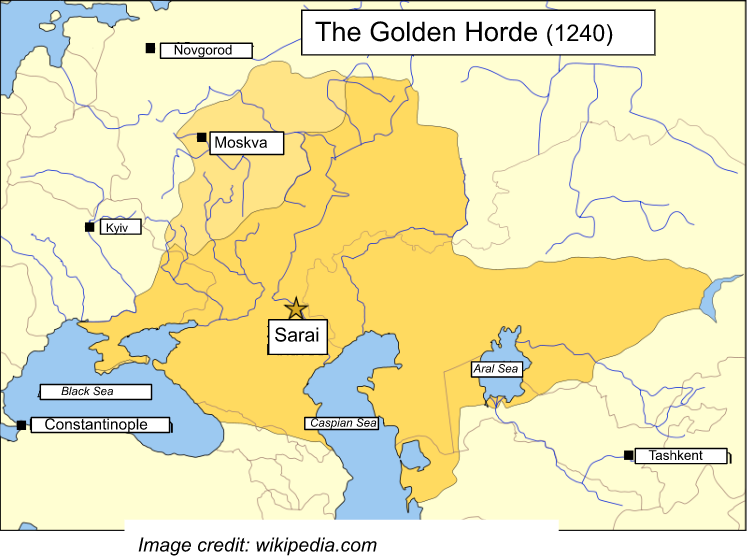

| Volhynia-Galicia in the southwest (modern Ukraine), Polotsk and Smolensk to the North (modern Belarus), and Vladimir-Suzdal (or Rostov-Suzdal) in the Northeast which included a small rural village called Moskva (or Moscow). Failing to take Kyiv, Rostov-Suzdal along with its rival principalities were easy targets for the Mongols to conquer in 1242 AD. For two centuries the Rus lands were ruled by the khanate of Kipchak, generally known as the Golden Horde. Tartars displaced Rus' princely administration and ruled directly. What makes this significant is that until 1380, Moskva of the old Rostov-Suzdal principality received its legal codes, prosperity, and state bureaucracy through |

Mongol rule. In other words, the Mongol empire “gave the conquered country the basic elements of future Muscovite statehood: autocracy, centralism, and serfdom” (Khara-Davan, 1925).

Another impact Mongol rule had on the future of the Russian state was its isolation from the West. The invasion worsened Moskva’s commercial ties with Europe so that it relied more heavily on trade and communication with the far east. According to historian E.

Another impact Mongol rule had on the future of the Russian state was its isolation from the West. The invasion worsened Moskva’s commercial ties with Europe so that it relied more heavily on trade and communication with the far east. According to historian E.

| Khara-Davan, the Mongols “summoned the Russian people from a provincial historical existence in small separated tribal and town principalities…on the broad road of statehood” (1925). Historian G. Vernadsky contrasted the institutions and spirit of Kievan Rus with those of Muscovy by comparing the pre-Mongol era with the post-Mongol era. Kievan political life had been free and diversified with monarchical, aristocratic, and |

democratic elements…, but under the Mongols this pattern changed drastically. Sharp rifts developed between east and west Rus. In the areas of the east most exposed to Mongol influences, monarchical power became highly developed. When the Rus princes recovered authority over them, they continued the Mongal systems. The Turkic origin of the Russian words for treasury (kazna) and treasurer (kaznachei) suggest that the Muscovite treasury followed the Mongol pattern. In a sense, Russia itself was a successor state of the Golden Horde (Vernadsky, 1953).

As a result, the Muscovite state was a gradual accumulation of authority and sovereignty by the grand prince of Moscow over the northern Rus lands that did not

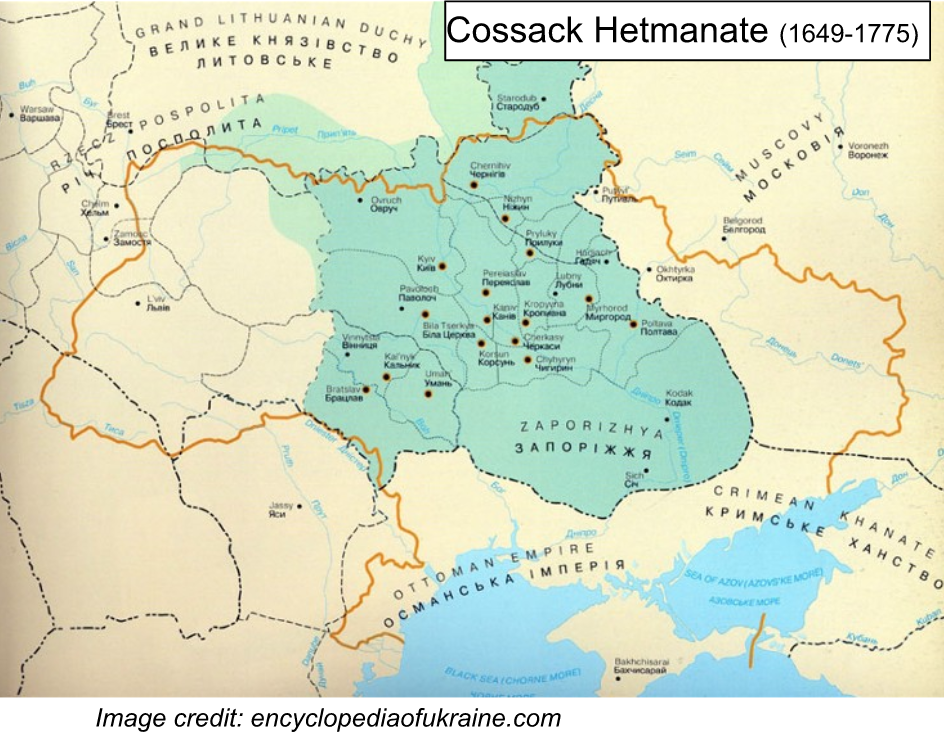

| include Kyiv in the south. Furthermore, modern Ukrainian identity emerged separately in language, customs, political organization, and European influences via commercial ties with Poland and Lithuania. This cultural and ethnic divide was further enhanced via the arrival of nomadic Cossacks in the 15th century. These new settlers, along with remnants of Volhynia -Galicia and escaped Russian serfs, formed the loosely confederated state of the |

Cossack Hetmanate under Khmelnytsky–credited by Ukrainian historians as the origin of the modern Ukrainian state after Galacia fell to Poland and Lithuania. However, Ukrainian lands gradually continued to lose their independence to surrounding empires until 1793 when most of Ukraine fell to the Russian Empire under Catherine the Great. Although Russia finally ruled directly over Kyiv, Ukrainians had lost many of their cultural links with northern Moskovites by the more than 500 years of separate history and cultural diffusion with other settlers. Nonetheless, if you are a Russian Imperialist who believes Moscow is the Third Rome, this half a millennium of separation must be undone. It may be said the cultural genocide of Ukraine began long before its official Russian annexation.

Myth By Orthodoxy

Centuries prior to Muskva’s occupation of Kyiv, the mythology of the Third Rome Theory was already taking root in religious authority that blended church and state to levels familiar to western medieval ‘Divine Right'. At the turn of the 14th century, there was an increasing recognition amongst Othodox church leadership of the need to relocate the center of church power, especially after the head of the Orthodox Church, known as the Metropolitan, had to flee Kyiv to take residence in Vladimir in the face of continuing and extensive Tatar violence towards the south of Ukraine. After a political struggle between the princes of Tver and Moscow for full power and prestige of the Orthodox see, the metropolitan chose Moscow in 1309 AD. Metropolitan Peter imparted to Moscow a religious prominence foreshadowing its future political successes as the “gatherer of Russian lands” where he was eventually entombed. This employed the moral authority of the church to support Moscow’s political ambitions. Once Moscow was finally able to cast off Mongol rule under Ivan III (Ivan the Great) in 1467, Muscovite expansion helped produce an imperial ideology under Ivan’s son, Vasili III. Like his father, Vasili used the title ‘Sovereign of All Russia’ and occasionally, ‘tsar’–meaning Caesar. Religious writers elaborated theories to explain his divine authority. According to Spiridon of Tver, Vasili’s Riurik family name was not only descended from Vladimir the Great of Kievan Rus, but also Augustus Caesar of the ancient Roman empire, even though there were no traceable descendants of Augustus for over a thousand years prior to this time. Out of this, the Third Rome Theory was formulated in 1510 when the Abbot Filofei of Pskov defined the idea to Tsar Vasili III. As with all empires, religious authority to rule and legitimacy for imperial expansion require mythical prestige rooted in historically recognized authority. Acting out a ‘Russian Manifest Destiny', the Third Rome theory and the grand prince’s title of Ruler of All Russians, gave legitimacy for the early Tsars to expand over all former territories of Keivan Rus. Since Church and political power went hand-in-hand, to resist Moscow rule would be to resist protection under God’s chosen political leader of the ‘true Christianity’.

Weaponizing the Church

Although the Soviet Era had restricted religious expression during the Cold War, Vladimir Putin has rejuvenated Tsarist imperial practices in absence of Soviet messiacic Marxism by using the Russian Orthodox Church (ROC) to provide his autocracy with the familiar religious mandate. Putin’s widely publicized appearances with Orthodox clergy have paid off for him both politically at home and in former Soviet spheres. The current Patriarch, Kirill has approved Putin’s war with Ukraine, even going as far as to call it a “holy war.” It is Kirill who quite often publicly calls for the construction of the Russian World, connecting the Russian-speaking and Orthodox Christian faith professing population. When Kirill became the Patriarch of the ROC in 2009, he presented his concept of the Russian World. He emphasized the “Slavic Orthodox Brotherhood”, resulting from the ancient period of Kievan Rus, along with other Slavic and Orthodox nations living especially in the territory of the former USSR; and even people who spiritually identify themselves with Russia and dream about the “All-Slavic Union” under the leadership of Russia (Solik, Solik, & Baar, 2019).

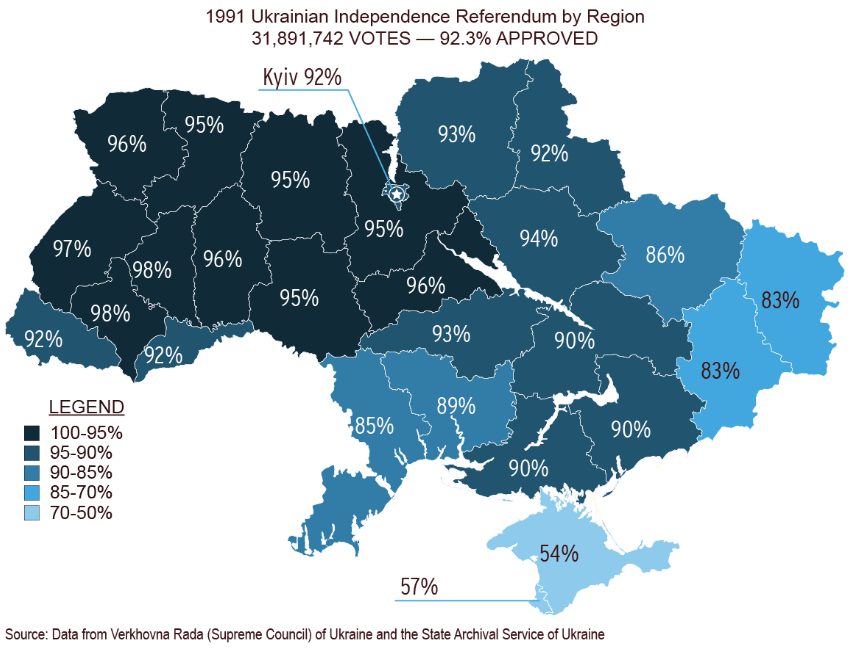

As demonstrated in an earlier blog on Propaganda, religion has historically been used to mobilize public support for state legitimacy and mobilization of the masses. Putin’s use of traditional Christianity is rooted in Tsarist Russia and calculated for political effect. Historically used as an instrument for Russifying newly acquired territories, researchers Solik & Baar (2019) found “The Russian Orthodox Church (ROC) as an institution is increasingly becoming an effective tool of the Russian concept of soft power in the post-Soviet space.” Since many Orthodox Churches in Europe are jurisdictionally tied to Moscow, ROC leaders train and visit these perishes often, and even influence their clergy to support Russian foreign policy. Using analysis of official documents and articles of the ROC and its jurisdictionally subordinates, Solik and Baar (2019) used the Republic of Moldova as a case study to investigate the effectiveness of this influence on public support for Moscow. A 2009 poll revealed 65% of Moldovans held a positive view of the EU. As an EU integration process began in 2014; however, the Moldovan Orthodox Church (MOC) in cooperation with the ROC launched an anti-EU offensive and agitation in the Moldovan society. Anti-European propaganda spread by Russian media and the ROC caused a widespread distrust of the EU and NATO in Moldova. Recent opinion polls clearly confirm this fact. By criticizing western support for gay rights and demogaging LBGTQ issues, a June 2017 poll showed that 57% of respondents think that Moldova should be closer to Russia and only 43% think it should be closer to Europe and the West, viewed as spiritually decadent. In addition, some 65% of Moldovans would vote against joining NATO, while 21% of respondents would vote for joining the military alliance. Prior to Putin’s annexation of Crimea, similar trends could be found in Ukraine in response to the Orange Revolution. Although a 1991 electoral map demonstrated Ukrainians heavily in favor of separation from Russia, the success of Kirill’s Russian World initiative was influential for many Russian speaking Ukrainians vulnerable to Kremlin propaganda.

Myth By Orthodoxy

Centuries prior to Muskva’s occupation of Kyiv, the mythology of the Third Rome Theory was already taking root in religious authority that blended church and state to levels familiar to western medieval ‘Divine Right'. At the turn of the 14th century, there was an increasing recognition amongst Othodox church leadership of the need to relocate the center of church power, especially after the head of the Orthodox Church, known as the Metropolitan, had to flee Kyiv to take residence in Vladimir in the face of continuing and extensive Tatar violence towards the south of Ukraine. After a political struggle between the princes of Tver and Moscow for full power and prestige of the Orthodox see, the metropolitan chose Moscow in 1309 AD. Metropolitan Peter imparted to Moscow a religious prominence foreshadowing its future political successes as the “gatherer of Russian lands” where he was eventually entombed. This employed the moral authority of the church to support Moscow’s political ambitions. Once Moscow was finally able to cast off Mongol rule under Ivan III (Ivan the Great) in 1467, Muscovite expansion helped produce an imperial ideology under Ivan’s son, Vasili III. Like his father, Vasili used the title ‘Sovereign of All Russia’ and occasionally, ‘tsar’–meaning Caesar. Religious writers elaborated theories to explain his divine authority. According to Spiridon of Tver, Vasili’s Riurik family name was not only descended from Vladimir the Great of Kievan Rus, but also Augustus Caesar of the ancient Roman empire, even though there were no traceable descendants of Augustus for over a thousand years prior to this time. Out of this, the Third Rome Theory was formulated in 1510 when the Abbot Filofei of Pskov defined the idea to Tsar Vasili III. As with all empires, religious authority to rule and legitimacy for imperial expansion require mythical prestige rooted in historically recognized authority. Acting out a ‘Russian Manifest Destiny', the Third Rome theory and the grand prince’s title of Ruler of All Russians, gave legitimacy for the early Tsars to expand over all former territories of Keivan Rus. Since Church and political power went hand-in-hand, to resist Moscow rule would be to resist protection under God’s chosen political leader of the ‘true Christianity’.

Weaponizing the Church

Although the Soviet Era had restricted religious expression during the Cold War, Vladimir Putin has rejuvenated Tsarist imperial practices in absence of Soviet messiacic Marxism by using the Russian Orthodox Church (ROC) to provide his autocracy with the familiar religious mandate. Putin’s widely publicized appearances with Orthodox clergy have paid off for him both politically at home and in former Soviet spheres. The current Patriarch, Kirill has approved Putin’s war with Ukraine, even going as far as to call it a “holy war.” It is Kirill who quite often publicly calls for the construction of the Russian World, connecting the Russian-speaking and Orthodox Christian faith professing population. When Kirill became the Patriarch of the ROC in 2009, he presented his concept of the Russian World. He emphasized the “Slavic Orthodox Brotherhood”, resulting from the ancient period of Kievan Rus, along with other Slavic and Orthodox nations living especially in the territory of the former USSR; and even people who spiritually identify themselves with Russia and dream about the “All-Slavic Union” under the leadership of Russia (Solik, Solik, & Baar, 2019).

As demonstrated in an earlier blog on Propaganda, religion has historically been used to mobilize public support for state legitimacy and mobilization of the masses. Putin’s use of traditional Christianity is rooted in Tsarist Russia and calculated for political effect. Historically used as an instrument for Russifying newly acquired territories, researchers Solik & Baar (2019) found “The Russian Orthodox Church (ROC) as an institution is increasingly becoming an effective tool of the Russian concept of soft power in the post-Soviet space.” Since many Orthodox Churches in Europe are jurisdictionally tied to Moscow, ROC leaders train and visit these perishes often, and even influence their clergy to support Russian foreign policy. Using analysis of official documents and articles of the ROC and its jurisdictionally subordinates, Solik and Baar (2019) used the Republic of Moldova as a case study to investigate the effectiveness of this influence on public support for Moscow. A 2009 poll revealed 65% of Moldovans held a positive view of the EU. As an EU integration process began in 2014; however, the Moldovan Orthodox Church (MOC) in cooperation with the ROC launched an anti-EU offensive and agitation in the Moldovan society. Anti-European propaganda spread by Russian media and the ROC caused a widespread distrust of the EU and NATO in Moldova. Recent opinion polls clearly confirm this fact. By criticizing western support for gay rights and demogaging LBGTQ issues, a June 2017 poll showed that 57% of respondents think that Moldova should be closer to Russia and only 43% think it should be closer to Europe and the West, viewed as spiritually decadent. In addition, some 65% of Moldovans would vote against joining NATO, while 21% of respondents would vote for joining the military alliance. Prior to Putin’s annexation of Crimea, similar trends could be found in Ukraine in response to the Orange Revolution. Although a 1991 electoral map demonstrated Ukrainians heavily in favor of separation from Russia, the success of Kirill’s Russian World initiative was influential for many Russian speaking Ukrainians vulnerable to Kremlin propaganda.

| Conflicts with Ukraine further suggest that Putin’s public affinity for Christianity may have more to do with geopolitics than religious sincerity. According to Mrachek & McCrum (2019), after Russia illegally annexed Crimea in 2014, Putin sought to justify his action by pointing to a shared religious and cultural history: |

Everything in Crimea speaks of our shared history and pride. This is the location of ancient Khersones, where Prince Vladimir was baptized. His spiritual feat of adopting Orthodoxy predetermined the overall basis of the culture, civilization, and human values that unite the peoples of Russia, Ukraine, and Belarus (cited by Mrachek & McCrum, 2019).

Furthermore, Putin’s use of religion has an added effect on the propaganda war serving his imperialist ambitions. This is simply an attempt to seduce former Soviet republics back under the sway of Russia. As Mrachek & McCrum point out, Putin’s strategy makes perfect sense given recent religious trends in the region. Orthodox Christianity has enjoyed a marked revival in Eastern Europe in the last two decades. “In nine of Russia’s regional neighboring states—Moldova, Greece, Armenia, Georgia, Serbia, Romania, Ukraine, Bulgaria, and Belarus—more than 70 percent of people identify as Orthodox, according to current Pew Research results.” This revival of Orthodoxy coincides with pro-Russian sentiment. The Pew Research, cited by Mrachek & McCrum, concludes:

[M]any Orthodox Christians—and not only Russian Orthodox Christians—express pro-Russia views. … Orthodox identity is tightly bound up with national identity, feelings of pride and cultural superiority, support for linkages between national churches and governments, and views of Russia as a bulwark against the West.

By cleverly casting himself as a belligerent in the culture war with the West, he has increased his popularity not only in eastern Europe, but among many conservative figures in America, including Pat Buchanan and Franklin Graham, who have been attracted to Putin’s rhetoric. With his rejection of homosexuality and divorce, he has found sympathy in conservative realms. However, Putin’s attempt to use the Orthodox Church to promote himself has caused a split in eastern orthodoxy. After the events of 2014, the Ukrainian Orthodox church formally separated from the Russian patriarchy of whose jurisdiction it had been under since 1686.

A separate Orthodox Church located in Ukraine, the birthplace of Keivan Rus, may hinder Putin's overall attempt at Pan-Slavism, protector of traditional Orthodoxy, and his nationalist followers who sell the Third Rome Theory, now rehashed as the Russian World. If all of these ideologies are key to Putin’s expansionism, then attempts at historical revisionism to delegitimize Ukraine as a state begin to make sense.

Conclusion

In spite of the Russian World and Third Rome Theory, Moskva (or Russia) directly received the majority of its political inheritance from the Mongols; not Kievan Rus (let alone the Byzantines). The Third Rome Theory was occasionally cited by Russian Tsars to promote imperialist expansions. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, the Third Rome Theory has once again entered the Russian psyche via Russian nationalists desperately seeking a place for Russia in the post-Soviet 21st century. Putin’s use of traditional Christianity is a calculated conduit for promoting pro-Russian sentiment in territories of eastern Europe that he wishes to expand influence. Although Ukraine has a much older and rich history that predates the Moscovite kingdom that emerged from the Mongol empire, this fact has no place in Russia's imperialist narratives. In stark contrast to Putin’s 2021 essay on Ukrainian ties to Russia, Ukraine and Ukrainian culture have existed separately for more than five centuries before eventual Russian conquest under Catherine the Great. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, Putin has increasingly weaponized the Orthodox Church to promote his propaganda to increase favorable views of Russia in the former Soviet sphere of influence and areas he wishes to expand. This strategy is not new, but rather that of a recycled foreign policy from Tsarist Russia. Bewildered by the rapid demise of the Soviet empire, many Russian nationalists have now turned to "Third Rome" for an understanding of Russia's place in world history. This ideology, though built on historical falsehoods, is unfortunately deeply rooted in Russian Orthodoxy and is used to gaslight eastern European nations, especially Ukraine, to undermine their statehood. By demagoguing social issues, the rhetoric has been so successful in fact it is attracting some conservatives in the west. As a result, a few right-wing commentators may find themselves more susseptable to Russian disinformation, unwittingly complicit in cultural genocide by spreading anti-Ukrainian views on their media platforms, and or less likely to support military aid to Ukraine.

What happened to Ukraine’s sense of national identity since the Tsarist occupation of 1793? Why has Russian revisionist history been so successful even in some contemporary western circles? Please check out Part II of this series on Galighting Ukraine to explore Russia’s long history of methodical and deliberate cultural genocide and even Russification of ethnic Ukrainians since Catherine the Great.

References

Klimenko, A. N. & Yurtaev, V. I. (2018). The “Moscow as the Third Rome” Concept: Its Nature and Interpretations since the 19th to Early 21st Centuries. Geopolítica(s) 9(2) 2018: 231-251. http://dx.doi.org/10.5209/GEOP.58910

MacKenzie, D. & Curran, M. W. (2002). A History of Russia, the Soviet Union, and Beyond: 6th edition. Wadsworth.

Mrachek, A. & McCrum, S. (2019). How Putin uses Russian Orthodoxy to grow his empire. The Heritage Foundation. https://www.heritage.org/europe/commentary/how-putin-uses-russian-orthodoxy-grow-his-empire#

Poe, M. T. (1997). Moscow, the Third Rome: The origins and transformations of a pivotal moment. THE NATIONAL COUNCIL FOR SOVIET AND EAST EUROPEAN RESEARCH. Harvard University. https://www.ucis.pitt.edu/nceeer/1997-811-25-Poe.pdf

Putin, V. (2021). On the historical unity of Russians and Ukrainians. Article by Vladimir Putin. Kremlin. http://en.kremlin.ru/events/president/news/66181#sel=68:55:L6w,68:122:vnx;77:33:36j,77:71:rQx;82:1:W3l,83:55:lx3

Solik, M., Solik, M., & Baar, V. (2019). The Russian Orthodox Church: An Effective Religious Instrument of Russia‘s “Soft” Power Abroad. The Case Study of Moldova. ORBIS SCHOLAE, 11(3), 13–41. https://doi.org/10.14712/1803-8220/9_2019

Vernadsky, G. (1953). The Mongols and Russia. New Haven.

[M]any Orthodox Christians—and not only Russian Orthodox Christians—express pro-Russia views. … Orthodox identity is tightly bound up with national identity, feelings of pride and cultural superiority, support for linkages between national churches and governments, and views of Russia as a bulwark against the West.

By cleverly casting himself as a belligerent in the culture war with the West, he has increased his popularity not only in eastern Europe, but among many conservative figures in America, including Pat Buchanan and Franklin Graham, who have been attracted to Putin’s rhetoric. With his rejection of homosexuality and divorce, he has found sympathy in conservative realms. However, Putin’s attempt to use the Orthodox Church to promote himself has caused a split in eastern orthodoxy. After the events of 2014, the Ukrainian Orthodox church formally separated from the Russian patriarchy of whose jurisdiction it had been under since 1686.

A separate Orthodox Church located in Ukraine, the birthplace of Keivan Rus, may hinder Putin's overall attempt at Pan-Slavism, protector of traditional Orthodoxy, and his nationalist followers who sell the Third Rome Theory, now rehashed as the Russian World. If all of these ideologies are key to Putin’s expansionism, then attempts at historical revisionism to delegitimize Ukraine as a state begin to make sense.

Conclusion

In spite of the Russian World and Third Rome Theory, Moskva (or Russia) directly received the majority of its political inheritance from the Mongols; not Kievan Rus (let alone the Byzantines). The Third Rome Theory was occasionally cited by Russian Tsars to promote imperialist expansions. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, the Third Rome Theory has once again entered the Russian psyche via Russian nationalists desperately seeking a place for Russia in the post-Soviet 21st century. Putin’s use of traditional Christianity is a calculated conduit for promoting pro-Russian sentiment in territories of eastern Europe that he wishes to expand influence. Although Ukraine has a much older and rich history that predates the Moscovite kingdom that emerged from the Mongol empire, this fact has no place in Russia's imperialist narratives. In stark contrast to Putin’s 2021 essay on Ukrainian ties to Russia, Ukraine and Ukrainian culture have existed separately for more than five centuries before eventual Russian conquest under Catherine the Great. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, Putin has increasingly weaponized the Orthodox Church to promote his propaganda to increase favorable views of Russia in the former Soviet sphere of influence and areas he wishes to expand. This strategy is not new, but rather that of a recycled foreign policy from Tsarist Russia. Bewildered by the rapid demise of the Soviet empire, many Russian nationalists have now turned to "Third Rome" for an understanding of Russia's place in world history. This ideology, though built on historical falsehoods, is unfortunately deeply rooted in Russian Orthodoxy and is used to gaslight eastern European nations, especially Ukraine, to undermine their statehood. By demagoguing social issues, the rhetoric has been so successful in fact it is attracting some conservatives in the west. As a result, a few right-wing commentators may find themselves more susseptable to Russian disinformation, unwittingly complicit in cultural genocide by spreading anti-Ukrainian views on their media platforms, and or less likely to support military aid to Ukraine.

What happened to Ukraine’s sense of national identity since the Tsarist occupation of 1793? Why has Russian revisionist history been so successful even in some contemporary western circles? Please check out Part II of this series on Galighting Ukraine to explore Russia’s long history of methodical and deliberate cultural genocide and even Russification of ethnic Ukrainians since Catherine the Great.

References

Klimenko, A. N. & Yurtaev, V. I. (2018). The “Moscow as the Third Rome” Concept: Its Nature and Interpretations since the 19th to Early 21st Centuries. Geopolítica(s) 9(2) 2018: 231-251. http://dx.doi.org/10.5209/GEOP.58910

MacKenzie, D. & Curran, M. W. (2002). A History of Russia, the Soviet Union, and Beyond: 6th edition. Wadsworth.

Mrachek, A. & McCrum, S. (2019). How Putin uses Russian Orthodoxy to grow his empire. The Heritage Foundation. https://www.heritage.org/europe/commentary/how-putin-uses-russian-orthodoxy-grow-his-empire#

Poe, M. T. (1997). Moscow, the Third Rome: The origins and transformations of a pivotal moment. THE NATIONAL COUNCIL FOR SOVIET AND EAST EUROPEAN RESEARCH. Harvard University. https://www.ucis.pitt.edu/nceeer/1997-811-25-Poe.pdf

Putin, V. (2021). On the historical unity of Russians and Ukrainians. Article by Vladimir Putin. Kremlin. http://en.kremlin.ru/events/president/news/66181#sel=68:55:L6w,68:122:vnx;77:33:36j,77:71:rQx;82:1:W3l,83:55:lx3

Solik, M., Solik, M., & Baar, V. (2019). The Russian Orthodox Church: An Effective Religious Instrument of Russia‘s “Soft” Power Abroad. The Case Study of Moldova. ORBIS SCHOLAE, 11(3), 13–41. https://doi.org/10.14712/1803-8220/9_2019

Vernadsky, G. (1953). The Mongols and Russia. New Haven.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed