The Age of Imperialism

To push forward an investigation without putting Japan’s perspective into context would be a mistake. Surely European expansion in Asia was seen as a threat to Japanese sovereignty and way of life. By the 19th century, Great Britain, Netherlands, France, Spain, Portugal, and arguably United States (via Philippines) all had colonial possessions in East Asia that were continuing to expand in territory and influence. However, no greater event alerted Japanese concerns than Britain’s domination of China during the Opium Wars (1839-1860). This led to Japan’s Meiji Restoration, which was a complete overhaul of Japan’s military, economic, and government institutions to match the West in industry and ingenuity. In a remarkably short period, 1868- 1902, Japan went from a feudal society of shogunates to a modernized industrial power that defeated the Russian navy in the Russo-Japanese War in 1904-05. Although Japan, too, began to acquire more territory and colonies in the process, the urgency and desperation for Japan to defend itself from foreign subjugation after China’s humiliation cannot be over emphasized.

Early Imperial Japan: Security Interests and the Need For Raw Materials

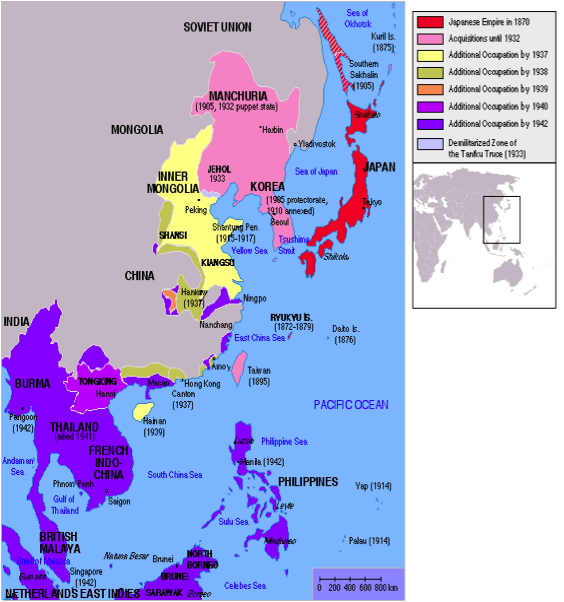

Was the nature of Japanese expansion imperialistic or that of righteous liberation from European powers? Some of Japan’s territorial expansion can be justified for security purposes such as Kuril Islands (1875) and Ryukyu Islands (1879). Perhaps the most controversial chapter in Japanese History was Japan’s colonization of neighboring states in East Asia prior to World War II. A Prussian military advisor to Japan, Klemens Meckel, warned that control over the Korean Peninsula was also of security interest for Japan stating that Korea was like a “dagger pointed at the heart of Japan.” As the Russian Empire, China and others struggled for influence over the Hermit Kingdom, the warning was dually noted by the Japanese military.

As stated previously, during the Meiji Period, Japan sought to make itself an imperial power capable of matching the West. However, Japan lacked many natural resources and natural land territory required for this to happen in the Gilded Age. France and Britain’s military power thrived not on their factories alone, but rather on the cheap raw materials from colonies that were the source of their wealth. Korea was known to have coal and iron deposits needed for Japan’s industrial factories and agricultural land needed to feed its growing population. As Korea found itself caught in the three-way dug-of-war, the road to Japan’s Annexation of Korea was secured after Japanese military victories in the First Sino-Japanese War, (1894-95) and the Russo-Japanese War ten years later. For similar reasons, Taiwan was also annexed shortly after the First Sino-Japanese War in 1895. With these annexations came cheap raw materials for industrial growth and border security. French intellectual, Francis Garnier saw nothing unrealistic or irresponsible with his statement “nations without colonies are dead.”

Japan Enters the Global Stage

By 1914, expanding industrial powers were competing world wide for markets and influence. Since most corners of the world were either colonized or spoken for at this time, China was viewed by many as not only the last unclaimed market, but, for Japan in particular, it was also a security concern. Since most of Japan’s neighbors were colonized by Europe, there was nowhere left for Japan to expand except westward into China. In 1914, Japan entered World War I on the side of the Allies in hopes of being rewarded with territorial gains in China. As a member of the Allies, Japan together with British forces occupied German holdings in China, such as Qingdao and Shandong, and Pacific island territories like Marianas, Carline, and Marshall Islands. After Germany’s surrender in 1918, Japan gained these German territories. Being the only non-White representatives at the Paris Peace Conference of 1919, many non-Western nations saw inspiration in Japan. At the conference, Japan proposed a clause on racial equality to be included in the League of Nations charter. However, not only was this proposal rejected, Japan was mostly ignored in the peace discussions on crucial negotiations that determined the post-war world. This marked an important turning point in Japan’s cooperation with the West. Frustrated with the Allies, Japan formally ended its alliance in 1923 and left the League of Nations in 1933.

Soon after the Great Depression, it became apparent to Japan just how much it relied on other nations such as the United States for iron and other raw resources to feed its hungry manufacturers. In the spirit of self-sufficiency, in 1933 Japan invaded Manchuria for their fertile soil, valuable forests, and extensive mineral resources sparking the second Sino-Japanese war with China (1933-45). The foundations for World War II were now in place.

The Greater East Asian Co-Prosperity Sphere

Commonly dismissed by historians as imperial propaganda, the Greater East Asian Co-Prosperity Sphere was first introduced by Japanese Foreign Minister Hachiro Arita over a radio broadcast in 1940. It called for economic and cultural unity among all East Asian nations against Western imperialists, or “Asia for the Asians”. It declared that all of East Asia should be free from Western control and should achieve economic self-sufficiency with Japan as its main protector. The Japanese Army leaders hailed the ideology as equivalent to USA’s Monroe Doctrine; that all of East Asia was as essential to Japan as Latin America was to the United States. The proposal was well received among audiences in South East Asian countries under colonial rule. Since most European powers were preoccupied at the moment fighting with Hitler, the Japanese seized the strategic timing to enforce the proposed ideology. Soon Japan was to launch its most aggressive and ambitious military campaigns yet. Since America’s military build up and possession of Philippines was seen as a strategic threat, the Japanese attacked the US naval fleet at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii in 1941. Shortly after bombing Pearl Harbor, the Japanese began a swift and impressive session of military victories throughout Asia, taking over Philippines, Hong Kong, Malaysia, Singapore, Burma, and Indonesia in only 6 months.

Few historians wish to acknowledge the welcome that some Southeast Asians gave Japanese invaders. Many nationalist movements against European occupation allied with Japan in their military endeavors. In Burma, members of the Burma Independence Army (BIA) accompanied advancing Japanese forces. In Indonesia, the overthrow of the Dutch colonial regime led to the release of Indonesian nationalists from prisons. Indonesia’s first president, Sukarno, decided to pursue his goal of true Indonesian independence by working with the Japanese. Hailed by many Indonesians as liberators, the Japanese allowed nationalist leaders to organize, establish chains of command and advance their nationalist aims through broadcasts in favor of independence. The Japanese also had some success in recruiting members of the Indian minority to enroll in the Indian National Army, a force created to liberate India from British rule. Perhaps the most troubling fact for western historians to rap their minds around is that this boost to South East Asian Nationalism made it impossible for South East Asia to become colonies ever again after World War II. The old pattern of European colonial dominance could never again be re-established after Japanese empowerment of Nationalists. Nowhere was this evidence more clear than the British and Dutch war in the East Indies shortly after WWII. The Netherlands fought a bitter war with Indonesia from 1945-49 until they finally gave up their attempt to maintain their colonial rule. France would also find the same difficulty when trying to return Indochinese possessions to their pre-war existence from 1945 till formally allowing independence in 1954. Although some resistance fighters existed before WWII, Japanese victories over allied forces and support for nationalist movements gave them the inspiration and organization necessary to resist their colonial masters.

Development of Infrastructure Under Japanese Rule

In addition to political self-sufficiency, many sympathetic observers have seen Japan’s rule over South East Asia and Korea as paramount to the modernization of their economic infrastructures. For Korea and Taiwan, the rice production more than doubled (though about half was imported to Japan Proper). The output of many cash crops in Taiwan, such as sugar, was almost entirely the work of Japanese authorities. Japan reduced the use of opium, furthered education and built extensive railways in Korea. The populations of Taiwan and Korea exploded under Japanese rule. In Korea, peasant farmers were converted into factory workers and economic output increased. After Korea became independent, the infrastructure developed under Japanese rule benefited their economic growth and was vital in North and South Korea’s emergence as developing industries after the war.

Although economic activity improved in Japan’s colonies, it came at an environmental cost. Like any other colonizing force, Japan’s own interests remained paramount. Many natural resources were exploited in Korea and Manchuria. Many landscapes were stripped bare of vegetation to meet Japanese demand for lumber, minerals, and agricultural land. Today, Koreans remember Japanese rule for its over consumption of their natural resources and wartime atrocities.

Japanese War Atrocities

Is the historic anger by Japan’s occupied neighbors justified? While many in South East Asia clearly rejoiced Japan as liberators, not all experiences were the same under Japanese rule. For Korea, there was no previous occupying force before Japan. Although nearly all Japanese annexations faced some degree of resistance which inevitably led to violence, perhaps no where else were long term effects of Japanese rule felt in every way of life than in Korea from 1910-1945. Unlike Burma or Indonesia, Korean patriots and politicians were assassinated rather than negotiated with, marking a wide contrast with the puppet governments Japan established in other colonies. Japanese rule in Korea was absolute with almost no local participation in the colonial governance. Although Japan can credit itself with building hundreds of schools and increasing literacy, the catch was a colonial education that systematically taught Koreans to give up their traditional culture in exchange for learning Japanese language and a revisionist version of history where Korea was viewed as a subculture of Japan. The control of education and newspapers was designed to provide a mechanism for the broad transmission of Japanese cultural and political values in order to legitimize permanent Japanese rule.

In China, nowhere else had Japanese rule faced as staunch a resistance. Many in the Japanese military were not expecting the Chinese to fight so bitterly. The Imperial Army’s response was that of methodical brutality throughout the Chinese countryside. Many unarmed prisoners and civilians were executed and tortured. The greatest of all these atrocities was in Nanjing where an estimated 300,000 were killed and many women fell victim to gang rapes by Japanese soldiers. The news was so shocking to the American media that it became the greatest factor in causing the US to end its oil exports to Japan. Other war crime atrocities can be sited such as the ‘comfort women’ from Korea and China who were virtually kidnapped and sent to the frontlines to sexually satisfy Japanese soldiers. This and biological medical experiments on civilians and prisoners of war were later classified as torture under the Geneva Convention and the post-war War Crimes Tribunals.

Why All Is Not Forgiven

Perhaps the most difficult barrier to current Northeast Asian relations is the Japanese denial of these atrocities and current geopolitics. In spite of the wealth of eyewitness testimonies and sources, some conservative Japanese politicians and historians deny that the atrocities ever took place. Some Japanese officials, including a governor of state broadcaster NHK, have denied that the Nanking Massacre ever happened. This strand of denial may seem irrational if not put in context with today’s political climate of the region. Asian governments often use the history of WWII to promote patriotism and a geopolitical agenda. The Chinese government, which recently made December 13th a national memorial day, in remembrance of the Nanking Massacre, often sees Japan as a regional and economic rival over disputed island territories and commercial markets. Meanwhile, Japan’s conservatives can be compared to America’s Tea Party movement which has promoted nationalism to such a degree that visiting the Yasukuni Shrine to pray has become a prerequisite for any politician seeking higher office. It is well known to any Japanese politician that any direct apology to China or visit to the Nanking Massacre museum would mean political suicide. Korea, who also has a territorial dispute with Japan, uses the historical atrocities as a political distraction for each election season. It is much safer to challenge an opponent’s record of condemnation of Japan than to debate such divisive issues as North Korea and US military presents.

Conclusion: Japan’s Revisionist History vs History Told By the Victors

What makes history a science worthy of attention is the examination of multiple points of view and challenging established narratives or assumed truths. As Benjamin Franklin once put it “Arguments wouldn’t last long if only one side laid the wrong.” The reason why so many Japanese revisionists are gaining ground is because they are partially correct. As with most states, Western powers usually exempt their own guilt and go along with a simpler narrative that paints a clear picture of good and evil when the simple fact is every side in a conflict believes they have the best of intentions. As a result, few have spoken up about Japan’s role to end colonialism and promote racial equality in a world controlled by Western powers and ideology. Although Japan created inexcusable crimes against humanity in the past, its methods of colonial control differ little with how England subjugated the subcontinent of India, or how the United Stated violated rights of African Americans and First Nations people in their expansion. During the Meiji government, Japanese officials learned everything they knew about how to colonize a people by mimicking the best. Their cultural indoctrination of Korea was borrowed from Britain’s colonial tactics in India. Though never pure in righteousness in their intent, Japan’s actions did help liberate Asia from Western masters. Since Japan lost the war, it is Japan who is forced to openly apologize to the world for their crimes while everyone else remains silent about their own. A more suitable use for history would be a group therapy session where all the nations of the world annually apologize for their historic crimes and pledge to work with one another to build a better future. This would only be fair as Japan at the start of the 20th century was just a product of its time—another industrial power competing in a life or death struggle with other nations for control of resources. That is all.

Eckert, C.J., Lee, K., Lew, Y.I., Robinson, M., Wagner, E.W. (1990). Korea Old And New: A History. Ilchokak Publishers. Korea Institute. Harvard University.

Latourette, K.S. (1964). A Short History of the Far East. Fourth Edition. Macmillan Company. New York.

Milton, O. (2004). Southeast Asia: An Introductory History. Ninth Edition. Allen & Unwin. National Library of Australia.

Simone, G. (2014). “A trip around Yushukan, Japan’s font of discord.” The Japan Times. 28 July 2014.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed