| By Timothy Holtgrefe November 2023 For several years prior to Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, President Vladimir Putin had devoted much of his time and effort to promoting false narratives and a revisionist history of Ukraine as early as 2005. However, the rhetorical gaslighting and denial of Ukraine’s rich cultural heritage is actually nothing new. In fact for Russian autocrats it is an historical continuity going back several hundred years in an effort to subjugate a race of people. |

What is surprising is not that the Russian Empire ‘russified’ their ethnic minorities, as all colonizers have performed similar practices, but that so many of these false narratives continue to persist into today’s political discourse regarding the current war in Ukraine; even in the West. This is part 5 of an HQ exclusive series to investigate Russia’s relentless attack on history. In this episode, we will explore Moscow’s revisionist history of the Second World War.

The Myth of The Great Patriotic War

Of all the lies and revisionist history put forward by the Kremlin, none are as vital to Putin's state-building mythology as that of the Second World War. Since the start of Vladimir Putin’s reign, Moscow has witnessed ever more grandiose parades marking the end of World War II, or what Russians call “The Great Patriotic War.” According to this historical narrative, the Soviet Union bore the brunt of the world’s burden to defeat Adolf Hitler’s Nazi empire and liberate Europe from Fascist tyranny. The Soviet Union defeated Nazi Germany on the eastern front, thereby earning the gratitude of millions and earning a crucial voice in postwar European order. As one high-ranking Russian official said, “Europe exists today thanks to those Soviet soldiers and officers who paid the ultimate price in order to enable its development” (cited by Domanska, 2019).

Of all the lies and revisionist history put forward by the Kremlin, none are as vital to Putin's state-building mythology as that of the Second World War. Since the start of Vladimir Putin’s reign, Moscow has witnessed ever more grandiose parades marking the end of World War II, or what Russians call “The Great Patriotic War.” According to this historical narrative, the Soviet Union bore the brunt of the world’s burden to defeat Adolf Hitler’s Nazi empire and liberate Europe from Fascist tyranny. The Soviet Union defeated Nazi Germany on the eastern front, thereby earning the gratitude of millions and earning a crucial voice in postwar European order. As one high-ranking Russian official said, “Europe exists today thanks to those Soviet soldiers and officers who paid the ultimate price in order to enable its development” (cited by Domanska, 2019).

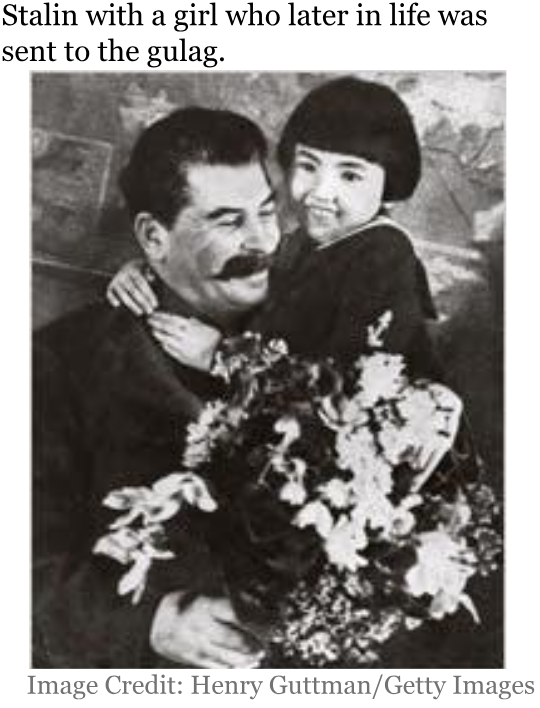

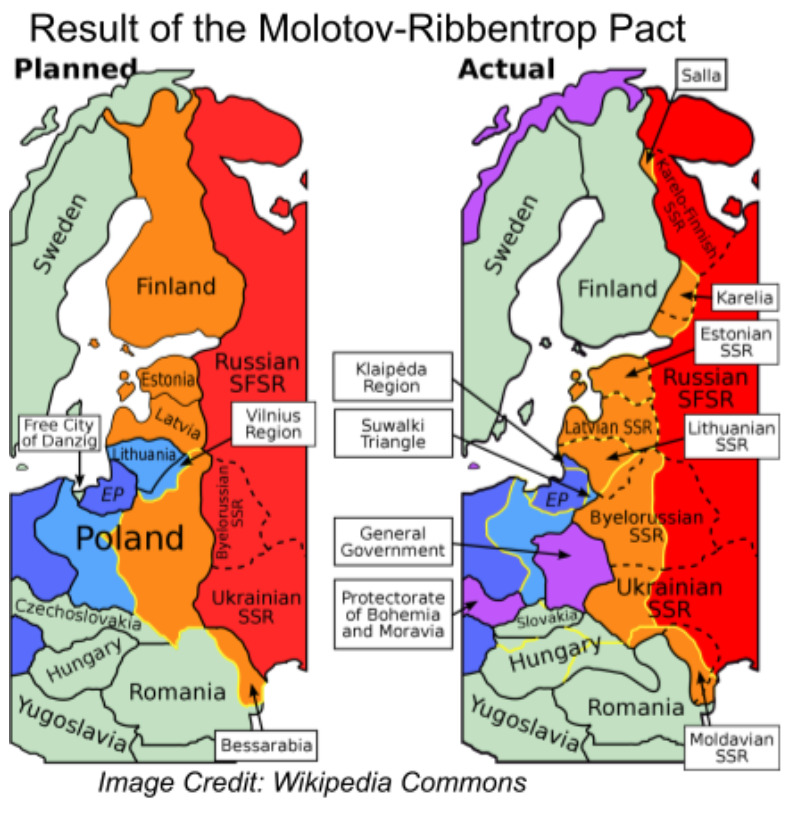

However, the idea of the Great Patriotic War is premised on the view that the war began in 1941, when Germany invaded the USSR, not in 1939, when Germany and the Soviet Union allied together to invade Poland. Also missing from Russia’s historical memory is Stalin’s own record of mass murder which is almost as comparable as Hitler’s. In fact, during the peace before the war, it was far worse.

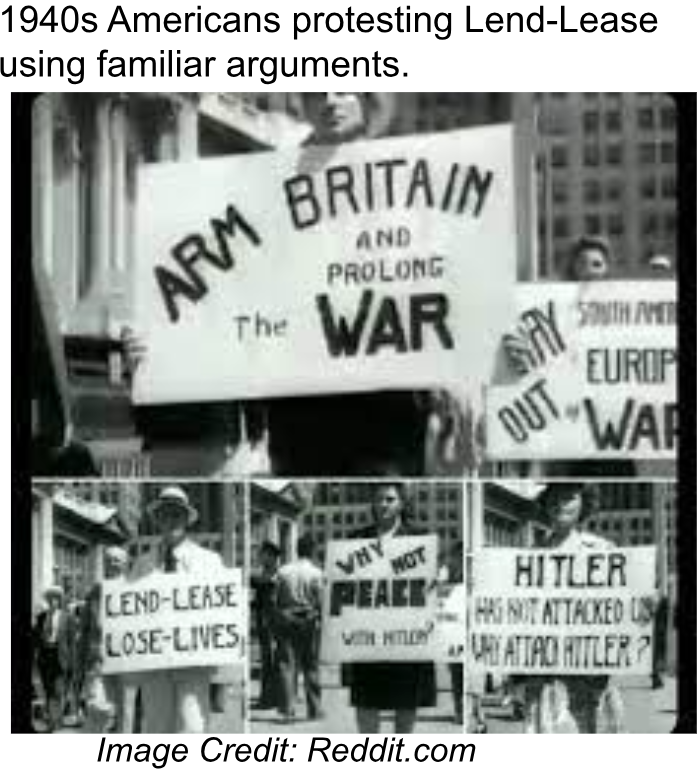

Under Gorbachev, the protocols of the 1939 Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact were disavowed as “mistaken.” (MacKenzie & Curran, p.538). However, when Putin nationalized Russian history curriculum and textbooks in 2003, Stalin’s atrocities were once again whitewashed and the role of Eastern Europeans in resisting Germany had been sidelined (Korostelina, 2010). The Russian historical narrative is also keen to devalue essential American aid to the Soviet Union through lend-lease. Additionally, and most critically to today’s political discourse, this revisionist storytelling does the greatest disservice to the Russian people and their understanding of the conflict in the following

Under Gorbachev, the protocols of the 1939 Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact were disavowed as “mistaken.” (MacKenzie & Curran, p.538). However, when Putin nationalized Russian history curriculum and textbooks in 2003, Stalin’s atrocities were once again whitewashed and the role of Eastern Europeans in resisting Germany had been sidelined (Korostelina, 2010). The Russian historical narrative is also keen to devalue essential American aid to the Soviet Union through lend-lease. Additionally, and most critically to today’s political discourse, this revisionist storytelling does the greatest disservice to the Russian people and their understanding of the conflict in the following

| ways: 1) it confuses the root causes of World War II; 2) leaves out Stalin’s role as Nazi collaborator and ally; 3) whitewashes Soviet atrocities against national minorities before, during, and after the war; 4) completely leaves out Soviet aggression that predates the alleged start of the war; and 5) effectively silences |

public debate by making any official comparisons between Hitler and Stalin illegal, rendering any national atonement for Russian crimes (past, present, or future) impossible.

Moreover, the goal for the Russian official memory of the “Great Patriotic War” is to promote unquestioning patriotism and a geopolitical agenda.

1. World War II was a colonial war against Ukraine

Hinted at but never fully appreciated, World War II mainly began due to the overlapping imperial aspirations between German and Soviet power over the fertile lands of Ukraine. Since the 1920s, the Nazis had a certain obsession with their manifest destiny in the east. After losing the First World War, Germany had no vast empire after it surrendered its modest overseas possessions. Unable to rival the British on the seas, Hitler saw eastern Europe as ripe for a new land empire (Mulligan, 1988, p.8). With 90% of German food imports from the Soviet Union coming from Soviet Ukraine, Germany would resolve its agricultural needs abroad (Kay, 2011, p.56).

Moreover, the goal for the Russian official memory of the “Great Patriotic War” is to promote unquestioning patriotism and a geopolitical agenda.

1. World War II was a colonial war against Ukraine

Hinted at but never fully appreciated, World War II mainly began due to the overlapping imperial aspirations between German and Soviet power over the fertile lands of Ukraine. Since the 1920s, the Nazis had a certain obsession with their manifest destiny in the east. After losing the First World War, Germany had no vast empire after it surrendered its modest overseas possessions. Unable to rival the British on the seas, Hitler saw eastern Europe as ripe for a new land empire (Mulligan, 1988, p.8). With 90% of German food imports from the Soviet Union coming from Soviet Ukraine, Germany would resolve its agricultural needs abroad (Kay, 2011, p.56).

| Known as lebensraum, the General Ost plan involved seizing farmland, destroying the mainly Polish and Ukrainian peasants who farmed it, and settling it with ethnic Germans (p.17-18). As revealed in his sequel to Mein Kampf, Hitler counted on victory in occupying Poland, Belarus, Ukraine, and western Russia to feed Germany during a future war with Great Britain and the United States. The plan was for a massive conquest in eastern Europe for the benefit of a master race against a “Jewish world conspiracy” blamed for Germany’s |

humiliating surrender after the First World War (Hitler, 1928, Ch.2). Herbert Backe, the Reich’s Food and Agriculture Minister, told Hitler in January 1941 that “the occupation of Ukraine would liberate us from every economic worry” (cited by Kay, 2011, p.211). Hitler himself said Germany must acquire Ukraine “so that no one is able to starve us again, like in the last war” (cited in p.50). It was believed that the conquest of Ukraine would first insulate Germans from the British blockade, and then the colonization of Ukraine would allow Germany to become a global power on the model of the United States (Snyder, 2012, p.161).

Mimicking Stalin’s method for pacifying Ukraine, starvation and colonization became German policy. It was discussed, agreed, formulated, distributed, and understood that 30 million people would have to starve to death (Kay, 2011, p.164). Professor Konrad Meyer drafted a series of plans for a vast eastern colony: Germans would deport, kill, assimilate, or enslave the native populations, and bring order and prosperity as 45 million people, mostly Slavs, were to disappear (p.100-1). Furthermore, they planned to destroy cities and industry, as well as cultural identities, to easily rule over them. Himmler mused, “Over a somewhat longer period of time it must be possible to cause the disappearance on our territory of the national conceptions Ukrainians, Gorals, Lemkos” (Cited by Snyder, 2012, p.145). Lastly, the guidelines for the Hunger Plan itself, dated May 23, 1941, stated:

Many tens of millions of people in this territory will become superfluous and will die or must emigrate to Siberia. Attempts to rescue the population there from death through the expense of the provisioning of Europe. They prevent the possibility of Germany holding out until the end of the war, they prevent Germany and Europe from resisting the blockade. With regard to this, absolute clarity must reign” (cited by Kay, 2011, p.133).

The Germans did in fact starve nearly 4 million people to death; however, they intended far worse than they achieved (Snyder, 2012, p.384).

For both Hitler and Stalin (and now Putin), Ukraine was more than a source of food. It was the place that would rescue their failed utopias from utter collapse, insulate their countries from isolation and sanctions, and remake the continent in their own image. Their violent regimes and their power all depended upon control of Ukraine’s fertile soil and its millions of agricultural laborers (p.19). During both reigns, the Stalinists and Nazis colonized Soviet Ukraine and the inhabitants of Ukraine suffered and suffered.

During the years both Hitler and Stalin were in power, more people were killed in Ukraine than anywhere else in Europe, or the world (p.20). This often overlooked and hanging question in history cannot be fully explained unless the motives for the Second World War are correctly understood. Just as Hitler believed control of Ukraine would rectify Germany’s humiliation, Putin today believes dominion over Ukraine can return Russia to its former glory after the breakup of the Soviet empire. Indeed a misunderstanding of the Second World War is just as dangerous today as ever before.

2. Soviet Ethnic Cleansing: Before WWII

Between 1933 and 1945, Hitler and Stalin would murder approximately 14 million civilians in Eastern Europe. Not a single one of them was a soldier nor combatant. Most were women, children, and the aged. The killings began with the political famine that Stalin directed at Soviet Ukraine, which claimed more than 3 million lives (See Part IV). It continued with Stalin’s Great Terror of 1937 and 1938, in which 700,000 people were shot, most of them peasants of national minorities, such as Poles and Ukrainians. The Soviets then cooperated with Nazis in the destruction of Poland and of its educated classes, killing some 200,000 people between 1939 and 1941 (Snyder, 2012, p.379-80).

Mimicking Stalin’s method for pacifying Ukraine, starvation and colonization became German policy. It was discussed, agreed, formulated, distributed, and understood that 30 million people would have to starve to death (Kay, 2011, p.164). Professor Konrad Meyer drafted a series of plans for a vast eastern colony: Germans would deport, kill, assimilate, or enslave the native populations, and bring order and prosperity as 45 million people, mostly Slavs, were to disappear (p.100-1). Furthermore, they planned to destroy cities and industry, as well as cultural identities, to easily rule over them. Himmler mused, “Over a somewhat longer period of time it must be possible to cause the disappearance on our territory of the national conceptions Ukrainians, Gorals, Lemkos” (Cited by Snyder, 2012, p.145). Lastly, the guidelines for the Hunger Plan itself, dated May 23, 1941, stated:

Many tens of millions of people in this territory will become superfluous and will die or must emigrate to Siberia. Attempts to rescue the population there from death through the expense of the provisioning of Europe. They prevent the possibility of Germany holding out until the end of the war, they prevent Germany and Europe from resisting the blockade. With regard to this, absolute clarity must reign” (cited by Kay, 2011, p.133).

The Germans did in fact starve nearly 4 million people to death; however, they intended far worse than they achieved (Snyder, 2012, p.384).

For both Hitler and Stalin (and now Putin), Ukraine was more than a source of food. It was the place that would rescue their failed utopias from utter collapse, insulate their countries from isolation and sanctions, and remake the continent in their own image. Their violent regimes and their power all depended upon control of Ukraine’s fertile soil and its millions of agricultural laborers (p.19). During both reigns, the Stalinists and Nazis colonized Soviet Ukraine and the inhabitants of Ukraine suffered and suffered.

During the years both Hitler and Stalin were in power, more people were killed in Ukraine than anywhere else in Europe, or the world (p.20). This often overlooked and hanging question in history cannot be fully explained unless the motives for the Second World War are correctly understood. Just as Hitler believed control of Ukraine would rectify Germany’s humiliation, Putin today believes dominion over Ukraine can return Russia to its former glory after the breakup of the Soviet empire. Indeed a misunderstanding of the Second World War is just as dangerous today as ever before.

2. Soviet Ethnic Cleansing: Before WWII

Between 1933 and 1945, Hitler and Stalin would murder approximately 14 million civilians in Eastern Europe. Not a single one of them was a soldier nor combatant. Most were women, children, and the aged. The killings began with the political famine that Stalin directed at Soviet Ukraine, which claimed more than 3 million lives (See Part IV). It continued with Stalin’s Great Terror of 1937 and 1938, in which 700,000 people were shot, most of them peasants of national minorities, such as Poles and Ukrainians. The Soviets then cooperated with Nazis in the destruction of Poland and of its educated classes, killing some 200,000 people between 1939 and 1941 (Snyder, 2012, p.379-80).

The Great Terror (1937-1938)

People belonging to national minorities “should be forced to their knees and shot like mad dogs” (cited by Jansen & Petrov, 2002, p.96). This is not a quote from an SS officer but a communist party leader in Stalin’s Russia. Although Hitler’s regime is well known for its racism and anti-semitism, a quarter of a million Soviet citizens were shot on essentially ethnic grounds between 1937-38. The most persecuted European national minority in the second half of the 1930s was not the 400,000 or so German Jews but the 600,000 or so Soviet Poles (Martin, 1998).

According to historian Timothy Snyder, German policies of mass killing did not begin to rival Soviet Russia’s until both leaders collaborated to invade Poland, sparking the Second World War. As part of an ‘anti-Kulak’ operation during the Great Terror of 1937-1938, the NKVD shot 70,868 inhabitants of Soviet Ukraine. Most of these victims of Order 00447 were Ukrainians, but a disproportionate number were Poles (Synder, 2012, p.84-6). When the difference in population size is taken into account, the Soviet system of concentration camps in late 1938 was about 26x larger than the German one. Therefore, “Soviet terror was incomparably more lethal prior to 1939” (p.86). As Snyder concludes, “the chances that a Soviet citizen would be executed in the kulak action were about 700x greater than the chances that a German citizen would be sentenced to death in Nazi Germany for any offense” (p.87).

Poles living in Soviet Ukraine and Belarus were scapegoated for everything from the continuation of nationalist movements to sharing the responsibility for the famine. Unlike Order 00447 which targeted minorities as alleged class enemies, Order 00485 treated an entire ethnic group as enemies of the state (p.90-3). Although the NKVD head assured the order punished espionage rather than

People belonging to national minorities “should be forced to their knees and shot like mad dogs” (cited by Jansen & Petrov, 2002, p.96). This is not a quote from an SS officer but a communist party leader in Stalin’s Russia. Although Hitler’s regime is well known for its racism and anti-semitism, a quarter of a million Soviet citizens were shot on essentially ethnic grounds between 1937-38. The most persecuted European national minority in the second half of the 1930s was not the 400,000 or so German Jews but the 600,000 or so Soviet Poles (Martin, 1998).

According to historian Timothy Snyder, German policies of mass killing did not begin to rival Soviet Russia’s until both leaders collaborated to invade Poland, sparking the Second World War. As part of an ‘anti-Kulak’ operation during the Great Terror of 1937-1938, the NKVD shot 70,868 inhabitants of Soviet Ukraine. Most of these victims of Order 00447 were Ukrainians, but a disproportionate number were Poles (Synder, 2012, p.84-6). When the difference in population size is taken into account, the Soviet system of concentration camps in late 1938 was about 26x larger than the German one. Therefore, “Soviet terror was incomparably more lethal prior to 1939” (p.86). As Snyder concludes, “the chances that a Soviet citizen would be executed in the kulak action were about 700x greater than the chances that a German citizen would be sentenced to death in Nazi Germany for any offense” (p.87).

Poles living in Soviet Ukraine and Belarus were scapegoated for everything from the continuation of nationalist movements to sharing the responsibility for the famine. Unlike Order 00447 which targeted minorities as alleged class enemies, Order 00485 treated an entire ethnic group as enemies of the state (p.90-3). Although the NKVD head assured the order punished espionage rather than

| ethnicity, there was simply nothing resembling a vast Polish plot to be found. In classic Stalinist style, the NKVD invented leads so as not to appear soft on traitors. Hence, precisely because there was no Polish plot, NKVD officers had little choice but to persecute Soviet Poles as well as anyone associated with Poland, Polish culture, or Roman Catholicism. As result, some 69 of the 100 members of the central committee of the Polish party were executed in the USSR (p.94). |

One Moscow NKVD chief understood the gist of the order: his organization should “destroy the Poles entirely” (cited in p.95). His officers looked for Polish names in city records. (Brown, 2005, p.158). As Synder calculates:

6,597 Poles were shot in Leningrad in the Polish operation. In the city, Poles were 34x more likely to be arrested than their fellow Soviet citizens. 89% of those sentenced in the Polish operation in this city were executed. On average throughout the Soviet Union, 78% of those arrested in the Polish operation were executed. The rest…were sentenced to…ten years in the Gulag. (Snyder, 2012, p.97).

Evgenia Babushkina, a victim of the Polish operation in Kuntsevo, was not even Polish, but her mother had once been a washerwoman for Polish diplomats, and so Evgenia was shot along with her mother (p.98). As in Nazi Germany, the targeting of an individual on ethnic grounds did not mean the person actually identified themself strongly with the nation in question. Likewise, death quotas for peasants and national minorities were sent down from Moscow to the regional NKVD offices in 1937 and in 1938 (p.435). In instances familiar to Putin’s abduction of Ukrainian children, the NKVD abducted Polish children and took them to orphanages so they would certainly not be raised as Poles (p.102). Though Poles only accounted for 0.4% of the general population, one-eighth of the 681,692 mortal victims of the Great Terror were Polish. In short, Soviet Poles were 40x more likely to die during the Great Terror than their fellow citizens (Jansen, 2002, p.97). This “Polish operation” would serve as a model for a series of other ethnic persecutions to come.

6,597 Poles were shot in Leningrad in the Polish operation. In the city, Poles were 34x more likely to be arrested than their fellow Soviet citizens. 89% of those sentenced in the Polish operation in this city were executed. On average throughout the Soviet Union, 78% of those arrested in the Polish operation were executed. The rest…were sentenced to…ten years in the Gulag. (Snyder, 2012, p.97).

Evgenia Babushkina, a victim of the Polish operation in Kuntsevo, was not even Polish, but her mother had once been a washerwoman for Polish diplomats, and so Evgenia was shot along with her mother (p.98). As in Nazi Germany, the targeting of an individual on ethnic grounds did not mean the person actually identified themself strongly with the nation in question. Likewise, death quotas for peasants and national minorities were sent down from Moscow to the regional NKVD offices in 1937 and in 1938 (p.435). In instances familiar to Putin’s abduction of Ukrainian children, the NKVD abducted Polish children and took them to orphanages so they would certainly not be raised as Poles (p.102). Though Poles only accounted for 0.4% of the general population, one-eighth of the 681,692 mortal victims of the Great Terror were Polish. In short, Soviet Poles were 40x more likely to die during the Great Terror than their fellow citizens (Jansen, 2002, p.97). This “Polish operation” would serve as a model for a series of other ethnic persecutions to come.

| In Soviet Belarus, NKVD commander Boris Berman accused local Belarusian communists of fomenting Belarusian nationalism. Once again Poles were to blame as masterminds behind any Belarusian disloyalty. Citizens who showed signs of Belarusian nationalism or cultural symbols were accused of being “fascists,” “Polish spies,” or both. The mass killings in Belarus included the deliberate destruction of the educated representatives of Belarusian national culture. 17,772 were sentenced to death in a killing field outside Minsk (Snyder, 2012, p.98-9). In western Soviet Russia, the Latvian operation saw 16,573 people shot as supposed spies for Latvia. A further 7,998 Soviet citizens were executed as spies for Estonia, and 9,078 |

as spies for Finland (p.104). When Soviet troops occupied Mongolia in 1937, authorities carried out their own ethnic terror in which 20,474 people were killed as "enemies of the revolution,” a figure roughly 4% of the nation’s total population at the time. In addition to Mongol nationalists and cultural intelligentsia, victims disproportionately included ethnic Buryats and Kazakhs (Kuromiya, 2014, p.13).

In sum, the national operations killed 247,157 people. These operations targeted national groups that, in total, represented only 1.6% of the soviet population, yet yielded no fewer than 36% of the fatalities of the Great Terror. Thus, one was 20x more likely to be killed in the Great Terror for being an ethnic minority (Morris, 2004, p.762). Few (and very possibly none) of the victims were engaged in espionage (Snyder, 2007, p.83-112).

Nonetheless, The Great Terror struck most heavily in Soviet Ukraine, particularly where there were ethnic Poles (Klimov, 1953, p.265). Shortly before Germans violently attacked Jews in Kristallnacht, the Soviet Union had just engaged in a campaign of ethnic murder on a much grander scale. By the end of 1938, the USSR had killed about 1000x more people on ethnic grounds than had Nazi Germany (Snyder, 2012, p.111).

Ethnic Cleansing During WWII

As the war began amidst Stalin’s occupation of east Poland in 1939, Stalin’s secret police chief Lavrenty Beria made clear in writing that he wanted the Polish prisoners of war shot and established a quota for the killings (p.135-6). One operation killed 21,892 Polish officers and others at Katyn as well as other sites in the Spring of 1940, mirroring Hitler’s killing campaigns in the western half of Poland. Prior to their executions, Beria allowed prisoners to correspond with loved ones to collect their addresses so that he may have their family members deported. Operation Troikas in western Belarus and western Ukraine deported 60,667 people to gulags (p.140).

When Stalin seized and annexed the Baltic states in 1940, the Soviet Union deported about 21,000 people from Lithuania, including educated elites (Angrick et al., 2012, p.46). Some 11,200 Estonians were also deported, including most of its political leadership (Snyder, 2012, p.193). Neighboring Latvia, too, had been annexed by the Soviet Union just one year before the German invasion. Some 21,000 citizens were deported by the Soviets just weeks before the Germans arrived in 1941. In both Latvia and Lithuania, the NKVD shot prisoners before retreating from the fast approaching Wehrmacht (Angrick et al., 2012, p.66-7).

During the Soviet occupation of east Poland, 315,000 Poles were taken from their homes for special settlement in distant gulags. During the passage alone, thousands of people perished from the extreme cold; and thousands more would die later from extreme exhaustion or hunger in the camps (Jolluck, 2002, p.41).

3. Stalin as Nazi Enabler and Collaborator

Whenever presented with opportunities to stop Hitler, Stalin consistently chose a different path. It is very likely that the Holocaust would not have taken place without Stalin enabling Hitler’s rise to power and invasion of Poland. Contrary to popular belief, German Jews made fewer than 3% of the victims of the Holocaust. Consequently, the vast majority of Jews were murdered in Eastern Europe after the invasion of Poland. In January 1940, just prior to Hitler’s first steps in initiating the Holocaust, the Soviet Union rejected Germany’s proposal to accept 2 million European Jews (Tooze, 2008, p.465).

In 1933 Stalin eased Hitler’s rise to power when he directed German communists to oppose German socialists rather than creating a united block against the Nazi Party (Snyder, 2012, p.419). In early 1939, after Hitler’s destruction of Czechoslovakia, Great Britain and France tried to bring the Soviet Union into a defensive coalition. However, Stalin saw more opportunity siding with Hitler and watching the Capitalist countries destroy themselves. According to Stalin, he and Hitler had a “common desire to get rid of the old equilibrium" (cited by Weinberg, 2005, p.25).

In sum, the national operations killed 247,157 people. These operations targeted national groups that, in total, represented only 1.6% of the soviet population, yet yielded no fewer than 36% of the fatalities of the Great Terror. Thus, one was 20x more likely to be killed in the Great Terror for being an ethnic minority (Morris, 2004, p.762). Few (and very possibly none) of the victims were engaged in espionage (Snyder, 2007, p.83-112).

Nonetheless, The Great Terror struck most heavily in Soviet Ukraine, particularly where there were ethnic Poles (Klimov, 1953, p.265). Shortly before Germans violently attacked Jews in Kristallnacht, the Soviet Union had just engaged in a campaign of ethnic murder on a much grander scale. By the end of 1938, the USSR had killed about 1000x more people on ethnic grounds than had Nazi Germany (Snyder, 2012, p.111).

Ethnic Cleansing During WWII

As the war began amidst Stalin’s occupation of east Poland in 1939, Stalin’s secret police chief Lavrenty Beria made clear in writing that he wanted the Polish prisoners of war shot and established a quota for the killings (p.135-6). One operation killed 21,892 Polish officers and others at Katyn as well as other sites in the Spring of 1940, mirroring Hitler’s killing campaigns in the western half of Poland. Prior to their executions, Beria allowed prisoners to correspond with loved ones to collect their addresses so that he may have their family members deported. Operation Troikas in western Belarus and western Ukraine deported 60,667 people to gulags (p.140).

When Stalin seized and annexed the Baltic states in 1940, the Soviet Union deported about 21,000 people from Lithuania, including educated elites (Angrick et al., 2012, p.46). Some 11,200 Estonians were also deported, including most of its political leadership (Snyder, 2012, p.193). Neighboring Latvia, too, had been annexed by the Soviet Union just one year before the German invasion. Some 21,000 citizens were deported by the Soviets just weeks before the Germans arrived in 1941. In both Latvia and Lithuania, the NKVD shot prisoners before retreating from the fast approaching Wehrmacht (Angrick et al., 2012, p.66-7).

During the Soviet occupation of east Poland, 315,000 Poles were taken from their homes for special settlement in distant gulags. During the passage alone, thousands of people perished from the extreme cold; and thousands more would die later from extreme exhaustion or hunger in the camps (Jolluck, 2002, p.41).

3. Stalin as Nazi Enabler and Collaborator

Whenever presented with opportunities to stop Hitler, Stalin consistently chose a different path. It is very likely that the Holocaust would not have taken place without Stalin enabling Hitler’s rise to power and invasion of Poland. Contrary to popular belief, German Jews made fewer than 3% of the victims of the Holocaust. Consequently, the vast majority of Jews were murdered in Eastern Europe after the invasion of Poland. In January 1940, just prior to Hitler’s first steps in initiating the Holocaust, the Soviet Union rejected Germany’s proposal to accept 2 million European Jews (Tooze, 2008, p.465).

In 1933 Stalin eased Hitler’s rise to power when he directed German communists to oppose German socialists rather than creating a united block against the Nazi Party (Snyder, 2012, p.419). In early 1939, after Hitler’s destruction of Czechoslovakia, Great Britain and France tried to bring the Soviet Union into a defensive coalition. However, Stalin saw more opportunity siding with Hitler and watching the Capitalist countries destroy themselves. According to Stalin, he and Hitler had a “common desire to get rid of the old equilibrium" (cited by Weinberg, 2005, p.25).

| When Hitler’s Foreign Minister Joachim von Ribbentrop visited Moscow in August 1939, swastikas decorated the airport of the capital which claimed to be an ideological state. The two regimes immediately found common ground in their mutual aspiration to destroy Poland. Nazi and Soviet rhetoric about the country were difficult to distinguish. They saw Poland as an “unreal creation” of the Versailles Treaty. The Irony was that Stalin had very recently justified the murder of more than 100,000 of his own citizens using the false claim that Poland had signed just such a secret deal with Germany under the cover of a nonaggression pact (Lukas, 2001, p.58-9). In September 1939, the Red Army and the Wehrmacht met in the middle of the country and organized a joint victory parade. On the 28th, Berlin and Moscow came to a second agreement over Poland on borders and |

friendship. Thanks to Stalin’s subsequent agreements, Hitler was able, in occupied Poland, to undertake his first policies of mass killing (Snyder, 2012, p.117).

Far from the world’s savior, Stalin’s pre-war strategy in 1941 was to encourage Hitler to fight wars in the west, in the hope that the capitalist powers would thus exhaust themselves, leaving the Soviets to collect the fallen fruit of a weakened Europe. “Destroy the enemies by their own hands,” was Stalin’s plan, “and remain strong to the end of the war” (cited in p.115). As a result, Hitler had won his battles in western Europe, as intended; however, too quickly for Stalin’s taste. He told himself and others that the warnings of an imminent German attack on the USSR were British propaganda, designed to divide Berlin and Moscow despite their manifest common interests (p.165). However, an unprovoked attack on the Soviet Union could only sound ludacris if Ukraine’s importance to Hitler was not fully understood. When Germany invaded the Soviet Union on June 22, 1941 in a surprise attack, Poland and the Soviet Union were suddenly transformed from enemies to allies.

The millions of civilians who died as a result of the Second World War were victims, in one way or another, of both regimes. Noncoincidently, Eastern European Jews account for nearly 90% of the victims of the Holocaust as Stalin enabled Hitler to target Poland’s Jews by their joint military adventure (p.384). In fact, it was Stalin’s Gulag systems, ethnic deportations, and mass political shootings and starvations that Hitler was attempting to imitate.

4. Soviet Aggression and Western Appeasement

In addition to its unprovoked invasion of Finland in 1939, the Soviet Union also extended its empire west, annexing all three of the independent Baltic States: Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania. The Soviets would deport about 17,500 people from Lithuania, 17,000 from Latvia, and 6,000 from Estonia and attempt to colonize these new territories with ethnic Russians (Weinberg, 2005, p.167-9).

When invading Poland in 1939, the Soviets claimed that their intervention was necessary since the Polish state no longer existed. Since there was no state to protect its citizens, went the argument, the Red Army entered the country on a ‘peacekeeping mission’ (Synder, 2012, p.124). Furthermore, Soviet propaganda claimed Poland’s large Ukrainian and Belarusian minorities were in particular need of rescue—oddly familiar language was used by Putin when invading Ukraine in 2014.

The millions of civilians who died as a result of the Second World War were victims, in one way or another, of both regimes. Noncoincidently, Eastern European Jews account for nearly 90% of the victims of the Holocaust as Stalin enabled Hitler to target Poland’s Jews by their joint military adventure (p.384). In fact, it was Stalin’s Gulag systems, ethnic deportations, and mass political shootings and starvations that Hitler was attempting to imitate.

4. Soviet Aggression and Western Appeasement

In addition to its unprovoked invasion of Finland in 1939, the Soviet Union also extended its empire west, annexing all three of the independent Baltic States: Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania. The Soviets would deport about 17,500 people from Lithuania, 17,000 from Latvia, and 6,000 from Estonia and attempt to colonize these new territories with ethnic Russians (Weinberg, 2005, p.167-9).

When invading Poland in 1939, the Soviets claimed that their intervention was necessary since the Polish state no longer existed. Since there was no state to protect its citizens, went the argument, the Red Army entered the country on a ‘peacekeeping mission’ (Synder, 2012, p.124). Furthermore, Soviet propaganda claimed Poland’s large Ukrainian and Belarusian minorities were in particular need of rescue—oddly familiar language was used by Putin when invading Ukraine in 2014.

| However, the Red Army engaged the Polish army wherever it encountered it. After staging a joint victory with Nazi Germany, Stalin spoke of an alliance with Germany “cemented in blood” (cited by Weinberg, 2005, p.57). Afterwards, the NKVD would arrest some 109,400 Polish citizens based on their level of education and importance to Polish culture. The typical sentence was eight years in the Gulag; about 8,513 of whom were sentenced to death (Snyder, 2012, p.126). Once the Polish state was destroyed, both regimes murdered tens of thousands of educated Poles and deported civilians to work camps by the hundreds of thousands (p.344). |

As part of the secret protocols of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Agreement, Germany moved on to conquer Denmark, Netherlands, Belgium, and Norway; the Soviets invaded Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Finland, and parts of Romania. Similar to Nazi pre war propaganda of the ‘Sudetenland,’ Soviet historians would have to retroactively consider eastern Europe as always having been Soviet, rather than as the booty of a war that Stalin had helped Hitler to begin (p.344). Stalin occupied the Baltic states militarily, engineered sham elections that, Moscow claimed, more than 99% approved their annexation to the USSR (MacKenzie & Curran, 2002, p.532). Today, as with their invasion of Ukraine, the Kremlin mainly defends Stalin’s actions on grounds of ‘security.’

Western Appeasement

Only when attacked was Stalin willing to side with the western democracies against Hitler. Although British and American allies could have illusions about Stalin, Polish officers and politicians could not afford such naivety. They had not forgotten that the Soviet Union was allied to Nazi Germany in 1939-1941, and that its occupation of eastern Poland had been genocidal.

When the mass graves of the Polish officers killed during Soviet occupation were discovered at Katyn, Stalin broke off diplomatic relations with the Polish government and blamed the German occupiers (Snyder, 2012, p.297). These actions left a lot of difficult questions for the Home Army of the Polish resistance: If Stalin would use his own massacre as a reason to end relations with the Polish government in exile, how could he be trusted to negotiate anything in good faith? And if the Soviet Union would not recognize the Polish government, a fellow ally, during a common struggle against Nazi Germany, what was the probability that it would support Polish sovereignty at the end of the war when the Soviet position was much stronger? (p.298).

The British and the Americans had other concerns. Stalin was a more crucial ally than any Polish government. It was more convenient for the British and Americans to accept the fictitious Soviet version of the massacre and blame the Germans. It was much easier for them to pressure their Polish ally to compromise than it was to stand up to Stalin. They wanted the Poles to accept the Soviet version that the Germans rather than the Soviets were responsible for the mass killings, which was false; and would have preferred that Poland grant the eastern half of its territory to the Soviet Union

Western Appeasement

Only when attacked was Stalin willing to side with the western democracies against Hitler. Although British and American allies could have illusions about Stalin, Polish officers and politicians could not afford such naivety. They had not forgotten that the Soviet Union was allied to Nazi Germany in 1939-1941, and that its occupation of eastern Poland had been genocidal.

When the mass graves of the Polish officers killed during Soviet occupation were discovered at Katyn, Stalin broke off diplomatic relations with the Polish government and blamed the German occupiers (Snyder, 2012, p.297). These actions left a lot of difficult questions for the Home Army of the Polish resistance: If Stalin would use his own massacre as a reason to end relations with the Polish government in exile, how could he be trusted to negotiate anything in good faith? And if the Soviet Union would not recognize the Polish government, a fellow ally, during a common struggle against Nazi Germany, what was the probability that it would support Polish sovereignty at the end of the war when the Soviet position was much stronger? (p.298).

The British and the Americans had other concerns. Stalin was a more crucial ally than any Polish government. It was more convenient for the British and Americans to accept the fictitious Soviet version of the massacre and blame the Germans. It was much easier for them to pressure their Polish ally to compromise than it was to stand up to Stalin. They wanted the Poles to accept the Soviet version that the Germans rather than the Soviets were responsible for the mass killings, which was false; and would have preferred that Poland grant the eastern half of its territory to the Soviet Union

| (p.298). The Western Soviet border, gifted to Stalin by Hitler, was confirmed by Churchill and Roosevelt in the Tehran Conference of 1943, which effectively endorsed the Molotov-Ribbentrop line. In a sense Poland was betrayed not only by the Soviet Union but also by its western Allies. Half of their country had already been conceded, without their consultation (p.298). In Potsdam, Washington and London agreed to Stalin’s ethnic expulsions in favor of an |

expanded western border of Poland as a compromise with Moscow in the expectation of Stalin allowing democratic elections. These never took place. Instead, communists intimidated and arrested opponents. The Polish regime held parliamentary elections in January 1947, but falsified the results (Ahonen, 2004, p.26-7).

Britain and France had gone to war five years earlier to preserve Polish independence. Now it was unable to protect them from their Soviet ally. The British press even echoed the Stalinist line, presenting the Poles as “adventurous” and “wayward,” rather than democratic allies seeking independence. George Orwell protested the “dishonesty and cowardice” of Britons for not aiding Poles in the Warsaw Uprising against Stalin’s wishes. Instead, the Red Army delayed their liberation of Warsaw as the Polish Home Army suffered the full might of their Nazi occupiers (Borodziej, 2006, p.94).

5. Why Comparing Hitler and Stalin is a Crime

The German reckoning with the Holocaust is exceptional and paradigmatic. However, the lack of their former Russian ally to follow suit has had modern consequences.

Britain and France had gone to war five years earlier to preserve Polish independence. Now it was unable to protect them from their Soviet ally. The British press even echoed the Stalinist line, presenting the Poles as “adventurous” and “wayward,” rather than democratic allies seeking independence. George Orwell protested the “dishonesty and cowardice” of Britons for not aiding Poles in the Warsaw Uprising against Stalin’s wishes. Instead, the Red Army delayed their liberation of Warsaw as the Polish Home Army suffered the full might of their Nazi occupiers (Borodziej, 2006, p.94).

5. Why Comparing Hitler and Stalin is a Crime

The German reckoning with the Holocaust is exceptional and paradigmatic. However, the lack of their former Russian ally to follow suit has had modern consequences.

| Since the early 2000s, Putin has made subtle efforts to restore Stalin’s image in the Russian official memory, even as the differences between Hitler and Stalin’s repression were not so significant for eastern Europeans. In some cases, the Soviet terror killed one sibling, the German terror the other (Snyder, 2012, p.149). The fact that it has been made illegal to compare Hitler and Stalin in 2014 is a chilling sign about |

Vladimir Putin’s vision for Russia. Without a hint of irony, Putin has criminalized all historical literature and their researchers comparing Hitler’s actions with Stalin, or himself; all while claiming to enforce a Russian law against the ‘Rehabilitation of Nazism’ (Coynash, 2021).

In 2014 and 2022, Putin invaded Ukraine using familiar language to Hitler and Stalin’s invasion of Poland. German and Soviet soldiers were instructed that Poland was not a real country as Wehrmacht officers and soldiers blamed Polish civilians for the horrors that befell them (p.120-1). In the regions that Germany annexed from Poland, Himmler was to remove the native population and replace it with Germans. Joseph Goebbels had his audiences believe that there were not only massive numbers of Germans in western Poland (which was greatly exaggerated), but they were suffering under cruel repressions (p.131). As with all authoritarian regimes, imagined victimhood is always key when promoting imperial expansion.

In 2014 and 2022, Putin invaded Ukraine using familiar language to Hitler and Stalin’s invasion of Poland. German and Soviet soldiers were instructed that Poland was not a real country as Wehrmacht officers and soldiers blamed Polish civilians for the horrors that befell them (p.120-1). In the regions that Germany annexed from Poland, Himmler was to remove the native population and replace it with Germans. Joseph Goebbels had his audiences believe that there were not only massive numbers of Germans in western Poland (which was greatly exaggerated), but they were suffering under cruel repressions (p.131). As with all authoritarian regimes, imagined victimhood is always key when promoting imperial expansion.

Making German crimes metaphysical and the Soviet ones meaningless has been politically convenient for Vladimir Putin’s regime. Since the 2010s, “you can’t compare” has been Russian memory policy and Vladimir Putin has done his best to export the idea (p.415-6). Today in Putin’s Russia, mentioning the indisputable fact that Stalin and Hitler both invaded Poland in 1939 will result in prison time.

In short, if one wishes to imitate the actions of Hitler or Stalin, it is helpful to first make any recognition of their similarities in behavior illegal.

Inflating the Dead

Russian leaders associate their country with the more or less official numbers of Soviet victims of the Second World War: 9 million military deaths, and 14 to 17 million civilian deaths. These lofty figures have been highly discredited. Chiefly they were never even counts but rather demographic projections. The numbers typically include Ukraine, Belarus, and the Baltics—and north eastern Romania. In other words, many of these victims were counted as “Soviet” simply because they were occupied by the Red Army after 1939. Not to mention, some were killed by the Soviet and not by the German invaders. Furthermore, most important of all for the high numbers are the Jews: not the Jews of Russia, of whom only about 60,000 died, but the Jews of Soviet Ukraine and Soviet Belarus (Ellman & Maksudov, 1994, p.674-9).

Contrary to Stalin’s (and Putin’s) portrayal of Ukrainians as Nazi collaborators, more Ukrainians died or were wounded fighting for Stalin than the combined losses of the United States, Great Britain and France. Like many ethnic groups after the war, their contribution was watered down and their own heroes side lined. Their inhabitants actually suffered more than the inhabitants of Poland or Russia in the 1930s and 1940s (Snyder, 2012, p.411). The Germans deliberately killed perhaps 3.2 million civilians and prisoners of war who were native of Soviet Russia: fewer in absolute terms than in Soviet Ukraine or in Poland. The number of Russian victims were not killed directly by the Germans but died from famine, deprivation, and Soviet repression during the war (Ellman & Maksudov, 1994, p.674-80) In short, the blame for many of the deaths is shared.

For certain, more Soviet citizens had died in the Second World War than any people in any war in recorded history. However, Stalinists had taken advantage of the suffering to justify Russian crimes. Rather than the result of Stalin’s complete disregard for human life, these deaths were necessary for the victory called “the Great Patriotic War.” Recognizing the ineffectiveness of Marxist propaganda in rallying popular support, Stalin turned to Russian nationalism. Stalin himself famously raised a toast to “the great Russian nation” just after the war’s end. The “Russian people,” he maintained, had won the war (Stalin, 1945). To be sure, about half the population of the USSR was Russian. According to Stalin’s chief propagandist, not only were all the victims of German killing policies “Soviet citizens,” but the greatest of all Soviet nations was the Russians. “The Russian people–the first among equals in the USSR’s family of peoples—are bearing the main burden of the struggle with the German occupiers” (Shcherbakov, 1942 cited by Snyder, p.228).

In short, if one wishes to imitate the actions of Hitler or Stalin, it is helpful to first make any recognition of their similarities in behavior illegal.

Inflating the Dead

Russian leaders associate their country with the more or less official numbers of Soviet victims of the Second World War: 9 million military deaths, and 14 to 17 million civilian deaths. These lofty figures have been highly discredited. Chiefly they were never even counts but rather demographic projections. The numbers typically include Ukraine, Belarus, and the Baltics—and north eastern Romania. In other words, many of these victims were counted as “Soviet” simply because they were occupied by the Red Army after 1939. Not to mention, some were killed by the Soviet and not by the German invaders. Furthermore, most important of all for the high numbers are the Jews: not the Jews of Russia, of whom only about 60,000 died, but the Jews of Soviet Ukraine and Soviet Belarus (Ellman & Maksudov, 1994, p.674-9).

Contrary to Stalin’s (and Putin’s) portrayal of Ukrainians as Nazi collaborators, more Ukrainians died or were wounded fighting for Stalin than the combined losses of the United States, Great Britain and France. Like many ethnic groups after the war, their contribution was watered down and their own heroes side lined. Their inhabitants actually suffered more than the inhabitants of Poland or Russia in the 1930s and 1940s (Snyder, 2012, p.411). The Germans deliberately killed perhaps 3.2 million civilians and prisoners of war who were native of Soviet Russia: fewer in absolute terms than in Soviet Ukraine or in Poland. The number of Russian victims were not killed directly by the Germans but died from famine, deprivation, and Soviet repression during the war (Ellman & Maksudov, 1994, p.674-80) In short, the blame for many of the deaths is shared.

For certain, more Soviet citizens had died in the Second World War than any people in any war in recorded history. However, Stalinists had taken advantage of the suffering to justify Russian crimes. Rather than the result of Stalin’s complete disregard for human life, these deaths were necessary for the victory called “the Great Patriotic War.” Recognizing the ineffectiveness of Marxist propaganda in rallying popular support, Stalin turned to Russian nationalism. Stalin himself famously raised a toast to “the great Russian nation” just after the war’s end. The “Russian people,” he maintained, had won the war (Stalin, 1945). To be sure, about half the population of the USSR was Russian. According to Stalin’s chief propagandist, not only were all the victims of German killing policies “Soviet citizens,” but the greatest of all Soviet nations was the Russians. “The Russian people–the first among equals in the USSR’s family of peoples—are bearing the main burden of the struggle with the German occupiers” (Shcherbakov, 1942 cited by Snyder, p.228).

| After the war, everyone in the new communist Europe would have to learn that the Russian nation had struggled and suffered the most. Russians without question would have to be the greatest victors and the greatest victims. Eastern Europeans had the least reason to accept the Russian version of martyrdom and innocence. The case would be a particularly hard one to make in places such as Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania, |

where the Second World War had begun and ended with Soviet occupation. It was all too difficult as well in western Ukraine, where nationalist partisans fought the Soviets for years after the war. Poles could not forget that the war had begun with allied German and Soviet armies invading their nation. However, the logical difficulties would be the greatest among Jews (p.431). Just as Stalin never singled out Ukrainians for their service or sacrifice, Jews were never singled out as victims of Hitler. Of the 5.7 million Jewish civilians had been murdered by the Germans, 2.6 million were Soviet citizens (Snyder, 2012, p.239 & 335). The fact that the Jews were the greatest victims of the war had to be forgotten. Instead, Stalin sought a way to present the war that would flatter the Russians while marginalizing the Jews and other national minorities and thus created the myth of “The Great Patriotic War” projected by Putin today.

Conservative estimates measure at least 10 million people inhabiting the lands of Ukraine today were killed between 1933 and 1945. Ukraine was at the center of both Stalinist and Nazi killing policies throughout the era of mass killing. Some 3.5 million people fell victim to Stalinist killing policies between 1933 and 1938, and then another 3.5 million to German killing policies between 1941 and 1944. Perhaps 3 million more inhabitants of Soviet Ukraine died in combat or as an indirect consequence of the war (Brandon & Lower, 2010, p.11). However, similar to the Russians, Ukrainian national memory was very much in competition for international martyrdom. Between 2005 and 2009, Ukrainian historians connected to state institutions repeated the inflated figure of 10 million deaths in the Holodomor alone. In early 2010, the official estimation of starvation deaths fell discreetly, to 3.94 million deaths (Snyder, 2012, p.404). This laudable (and unusual) downward adjustment brought the official position closer to the truth. Yet in Russia and Belarus, young people are still taught that the figure of their own civilian dead was not 1 in 5 but 1 in 3. These governments that celebrate the Soviet legacy deny the lethality of Stalinism, placing all the blame on Germans or more generally on the West (Goujon, 2010, p.18). All while inflating their martyrdom to silence victims of Russian aggression yesterday and today.

How These Myths Gaslight Ukraine Today

Stalin’s idea of the “Great Patriotic War” contains purposeful confusion. Although the war on Soviet territory was fought and won chiefly in Soviet Belarus and in Soviet Ukraine, Russians were to be honored the most, even as more Jewish, Belarusian, and Ukrainian civilians had been killed than Russians.

Since the surprised Red Army initially took such horrible losses, its ranks were filled by local Belarusian and Ukrainian conscripts throughout the war (Snyder, 2012, p.335). Frustrated with the lack of progress in taking Kyiv in the Summer of 1941, Hitler decided to send divisions from Army Group Center to aid Army Group South in the battle for Kyiv. This decision of Hitler’s delayed the march of Army Group Center on Moscow, which was their main target (p.205). In other words, stiff resistance in Ukraine likely saved the Soviet Union from collapse.

The misuse and revision of history has its consequences. Russia can negate any debt the world may feel it owes Ukraine and invade its territory, as it did in 2014, claiming to prevent a Holocaust. Russian memory law can leverage the Holocaust to ban criticism of Stalin and the general public noticing patterns in Putin’s behavior. The Holocaust is so exceptional, runs the logic of Russian memory law, that mentioning Soviet crimes amounts to its denial (p.420).

Many Stalinists and their sympathizers today, explain the losses from the famines and The Great Terror as necessary for the construction of a just and secure Soviet state. Our contemporary culture of commemoration takes for granted that memory prevents murder (p.401).

Conclusion

Glorifying elements of the Soviet past and blurring the lines over Stalin's brutal legacy has become a political tool for Putin, who has exploited nationalism to prop up his rule, now entering its third decade. Both Nazi Germany and Soviet Russia murdered the innocent by ethnicity. (p.435).

Despite Russian narratives of martyrdom, World War II began as a colonial war in Ukraine which, per capita, suffered far worse than Soviet Russia. In addition to its unprovoked invasion of Finland in 1939, the Soviet Union also extended its empire west, annexing all three of the independent Baltic States: Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania. The Soviets would deport their educated and cultural elite before attempting to colonize these new territories with ethnic Russians.

Indeed Russia did not fight Nazi Germany until they were betrayed and attacked by their ally. According to Putin’s Great Patriotic ‘Mythology,’ Russia cannot be criticized for its crimes because the Soviet Union was attacked by and then defeated Nazi Germany. (p.418).

The genocidal and aggressive similarities between Stalin and Hitler are enough inconvenience to Putin’s state-building mythology to make their comparisons illegal, particularly since his own ambitions mirror these authoritarians of the past. Like Putin, the Nazis and the Bolsheviks all have rejected democracy and sought imperial dominion through Ukraine while weaponizing global access to its food. Today, Putin attacks grain silos and exports departing the port of Odesa to other nations. Whereas Hitler envisioned a vast German empire arranged to assure the prosperity of Germans at the expense of others, Putin envisions a large Russian Empire for Russians at the expense of everyone.

Just as NATO is Putin’s excuse for genocide of Ukrainians today, Japanese military expansion and Polish neutrality were Stalin’s excuse to murder Estonians, Latvians, Belorussians, Ukrainians, Kazaks, Tuvians, Buryatians, Mongols, Tatars, Circassians, Poles and many more, while ethnically displacing Koreans and Chinese in the far east with mass deportations.

Like Putin today, both Stalin and Hitler believed the conquest of Ukraine would insulate their empires from western blockade, making them a global power in the model of the United States. Stalin kept his plans a secret. But what do you do in the digital age where nearly nothing can be kept secret for long? Disinformation.

In the next episode of this series, we will explore Stalin and Putin’s revisionist history to paint eastern European national movements as Nazi collaborators, particularly Ukraine.

Conservative estimates measure at least 10 million people inhabiting the lands of Ukraine today were killed between 1933 and 1945. Ukraine was at the center of both Stalinist and Nazi killing policies throughout the era of mass killing. Some 3.5 million people fell victim to Stalinist killing policies between 1933 and 1938, and then another 3.5 million to German killing policies between 1941 and 1944. Perhaps 3 million more inhabitants of Soviet Ukraine died in combat or as an indirect consequence of the war (Brandon & Lower, 2010, p.11). However, similar to the Russians, Ukrainian national memory was very much in competition for international martyrdom. Between 2005 and 2009, Ukrainian historians connected to state institutions repeated the inflated figure of 10 million deaths in the Holodomor alone. In early 2010, the official estimation of starvation deaths fell discreetly, to 3.94 million deaths (Snyder, 2012, p.404). This laudable (and unusual) downward adjustment brought the official position closer to the truth. Yet in Russia and Belarus, young people are still taught that the figure of their own civilian dead was not 1 in 5 but 1 in 3. These governments that celebrate the Soviet legacy deny the lethality of Stalinism, placing all the blame on Germans or more generally on the West (Goujon, 2010, p.18). All while inflating their martyrdom to silence victims of Russian aggression yesterday and today.

How These Myths Gaslight Ukraine Today

Stalin’s idea of the “Great Patriotic War” contains purposeful confusion. Although the war on Soviet territory was fought and won chiefly in Soviet Belarus and in Soviet Ukraine, Russians were to be honored the most, even as more Jewish, Belarusian, and Ukrainian civilians had been killed than Russians.

Since the surprised Red Army initially took such horrible losses, its ranks were filled by local Belarusian and Ukrainian conscripts throughout the war (Snyder, 2012, p.335). Frustrated with the lack of progress in taking Kyiv in the Summer of 1941, Hitler decided to send divisions from Army Group Center to aid Army Group South in the battle for Kyiv. This decision of Hitler’s delayed the march of Army Group Center on Moscow, which was their main target (p.205). In other words, stiff resistance in Ukraine likely saved the Soviet Union from collapse.

The misuse and revision of history has its consequences. Russia can negate any debt the world may feel it owes Ukraine and invade its territory, as it did in 2014, claiming to prevent a Holocaust. Russian memory law can leverage the Holocaust to ban criticism of Stalin and the general public noticing patterns in Putin’s behavior. The Holocaust is so exceptional, runs the logic of Russian memory law, that mentioning Soviet crimes amounts to its denial (p.420).

Many Stalinists and their sympathizers today, explain the losses from the famines and The Great Terror as necessary for the construction of a just and secure Soviet state. Our contemporary culture of commemoration takes for granted that memory prevents murder (p.401).

Conclusion

Glorifying elements of the Soviet past and blurring the lines over Stalin's brutal legacy has become a political tool for Putin, who has exploited nationalism to prop up his rule, now entering its third decade. Both Nazi Germany and Soviet Russia murdered the innocent by ethnicity. (p.435).

Despite Russian narratives of martyrdom, World War II began as a colonial war in Ukraine which, per capita, suffered far worse than Soviet Russia. In addition to its unprovoked invasion of Finland in 1939, the Soviet Union also extended its empire west, annexing all three of the independent Baltic States: Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania. The Soviets would deport their educated and cultural elite before attempting to colonize these new territories with ethnic Russians.

Indeed Russia did not fight Nazi Germany until they were betrayed and attacked by their ally. According to Putin’s Great Patriotic ‘Mythology,’ Russia cannot be criticized for its crimes because the Soviet Union was attacked by and then defeated Nazi Germany. (p.418).

The genocidal and aggressive similarities between Stalin and Hitler are enough inconvenience to Putin’s state-building mythology to make their comparisons illegal, particularly since his own ambitions mirror these authoritarians of the past. Like Putin, the Nazis and the Bolsheviks all have rejected democracy and sought imperial dominion through Ukraine while weaponizing global access to its food. Today, Putin attacks grain silos and exports departing the port of Odesa to other nations. Whereas Hitler envisioned a vast German empire arranged to assure the prosperity of Germans at the expense of others, Putin envisions a large Russian Empire for Russians at the expense of everyone.

Just as NATO is Putin’s excuse for genocide of Ukrainians today, Japanese military expansion and Polish neutrality were Stalin’s excuse to murder Estonians, Latvians, Belorussians, Ukrainians, Kazaks, Tuvians, Buryatians, Mongols, Tatars, Circassians, Poles and many more, while ethnically displacing Koreans and Chinese in the far east with mass deportations.

Like Putin today, both Stalin and Hitler believed the conquest of Ukraine would insulate their empires from western blockade, making them a global power in the model of the United States. Stalin kept his plans a secret. But what do you do in the digital age where nearly nothing can be kept secret for long? Disinformation.

In the next episode of this series, we will explore Stalin and Putin’s revisionist history to paint eastern European national movements as Nazi collaborators, particularly Ukraine.

References

Ahonen, P. (2004). After the Expulsion: West Germany and Eastern Europe 1945-1990. Oxford University Press.

Angrick, A., Klein, P., and Brandon, R. (2012). The “Final Solution” in Riga: Exploitation and Annihilation, 1941-1944. Berghahn Books.

Borodziej, W. (2006). The Warsaw Uprising of 1944. (B. Harshav trans.) University of Wisconsin Press.

Brandon, R. and Lower, W. (2010). The Shoah in Ukraine: History, Testimony, Memorialization. Indiana University Press.

Brown, K. (2005). A Biography of No Place: From Ethnic Borderland to Soviet Heartland. Harvard University Press.

Coynash, H. (2021, July 5). Comparing Stalin to Hitler could soon get you prosecuted in Russia, saying they both invaded Poland already has. Human Rights in Ukraine. https://khpg.org/en/1608809059

Domanska, M. (2019). The myth of the Great Patriotic War as a tool of the Kremlin’s great power policy. Centre for Eastern Studies. v316. https://www.osw.waw.pl/sites/default/files/Commentary_316.pdf

Ellman, M., & Maksudov, S. (1994). Soviet deaths in the Great Patriotic War: a note. Europe-Asia studies, 46(4), 671–680. https://doi.org/10.1080/09668139408412190

Goujon, A. (2010). Memorial Narratives of WWII Partisans and Genocide in Belarus. East European Politics and Societies, 24(1), 6-25. https://doi.org/10.1177/0888325409355818

Hitler, A. (1928). Zweites Buch. (K. Smith, trans.) Hitler’s Second Book: The Unpublished Sequel to Mein Kampft. Enigma Books https://www.google.com/books/edition/Hitler_s_Second_Book/mg64pgftN7gC?hl=en&gbpv=1

Hoffmann, D. L. (2021). The Memory of the Second World War in Soviet and Post-Soviet Russia. Routledge.

Jansen, M. & Petrov, N. (2002). Stalin's Loyal Executioner: People's Commissar Nikolai Ezhov, 1895-1940. Hoover Institution Press.

Jolluck, K. R. (2002). Exile and Identity: Polish Women in the Soviet Union during World War II. University of Pittsburgh Press.

Kay, A. J. (2011). Exploitation, Resettlement, Mass Murder: Political and Economic Planning for German Occupation Policy in the Soviet Union, 1940-1941. Berghahn Books.

Klimov, G. (1953). The Terror Machine - The Inside Story Of The Soviet Administration In Germany. Praeger Publishing.

Korostelina, K. (2010). War of textbooks: History education in Russia and Ukraine. Communist and Post-Communist Studies, 43(2), 129–137. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.POSTCOMSTUD.2010.03.004

Kuromiya, H. (2014). Stalin's Great Terror and the Asian Nexus, Europe-Asia Studies, 66:5, 775-793, DOI: 10.1080/09668136.2014.910940

Lukas, J. (2001). The Last European War: September 1939 - December 1941. Yale University Press.

MacKenzie, D. & Curran, M. W. (2002). A History of Russia, the Soviet Union, and Beyond: 6th edition. Wadsworth.

Martin, T. (1998). The origins of Soviet ethnic cleansing. The Journal of Modern History, 70(4), 813–861. https://doi.org/10.1086/235168

Morris, J. (2004). The Polish Terror: Spy Mania and Ethnic Cleansing in the Great Terror. Europe-Asia Studies, 56(5), 751–766. https://doi.org/10.1080/0966813041000235137

Mulligan, T. P. (1988). The Politics of Illusion and Empire: German Occupation Policy in the Soviet Union, 1942-1943. Praeger.

Snyder, T. (2012). Bloodlands: Europe Between Hitler and Stalin. Basic Books.

Synder, T. (2007). Sketches from a Secret War: A Polish Artist’s Mission to Liberate Soviet Ukraine. Yale University Press.

Stalin, J. V. (1945). Toast to the Russian People at a Reception in Honour of Red Army Commanders Given by the

Soviet Government in the Kremlin on Thursday, May 24, 1945. Marxist Internet Archive. https://www.marxists.org/reference/archive/stalin/works/war/index.htm

Tooze, A. (2008). Wages of Destruction: The Making and Breaking of the Nazi Economy. Penguin Books.

Weinberg, G. L. (2005). A World at Arms: A Global History of World War II. Cambridge University Press.

Wesolowsky, T. & Luxmoore, M. (2019). Molotov-Ribbentrop What? Do Russians Know Of Key World War II Pact? Radio Free Europe Radio Liberty. https://www.rferl.org/a/molotov-ribbentrop-what-do-russians-know-of-key-wwii-pact/30123950.html

Ahonen, P. (2004). After the Expulsion: West Germany and Eastern Europe 1945-1990. Oxford University Press.

Angrick, A., Klein, P., and Brandon, R. (2012). The “Final Solution” in Riga: Exploitation and Annihilation, 1941-1944. Berghahn Books.

Borodziej, W. (2006). The Warsaw Uprising of 1944. (B. Harshav trans.) University of Wisconsin Press.

Brandon, R. and Lower, W. (2010). The Shoah in Ukraine: History, Testimony, Memorialization. Indiana University Press.

Brown, K. (2005). A Biography of No Place: From Ethnic Borderland to Soviet Heartland. Harvard University Press.

Coynash, H. (2021, July 5). Comparing Stalin to Hitler could soon get you prosecuted in Russia, saying they both invaded Poland already has. Human Rights in Ukraine. https://khpg.org/en/1608809059

Domanska, M. (2019). The myth of the Great Patriotic War as a tool of the Kremlin’s great power policy. Centre for Eastern Studies. v316. https://www.osw.waw.pl/sites/default/files/Commentary_316.pdf

Ellman, M., & Maksudov, S. (1994). Soviet deaths in the Great Patriotic War: a note. Europe-Asia studies, 46(4), 671–680. https://doi.org/10.1080/09668139408412190

Goujon, A. (2010). Memorial Narratives of WWII Partisans and Genocide in Belarus. East European Politics and Societies, 24(1), 6-25. https://doi.org/10.1177/0888325409355818

Hitler, A. (1928). Zweites Buch. (K. Smith, trans.) Hitler’s Second Book: The Unpublished Sequel to Mein Kampft. Enigma Books https://www.google.com/books/edition/Hitler_s_Second_Book/mg64pgftN7gC?hl=en&gbpv=1

Hoffmann, D. L. (2021). The Memory of the Second World War in Soviet and Post-Soviet Russia. Routledge.

Jansen, M. & Petrov, N. (2002). Stalin's Loyal Executioner: People's Commissar Nikolai Ezhov, 1895-1940. Hoover Institution Press.

Jolluck, K. R. (2002). Exile and Identity: Polish Women in the Soviet Union during World War II. University of Pittsburgh Press.

Kay, A. J. (2011). Exploitation, Resettlement, Mass Murder: Political and Economic Planning for German Occupation Policy in the Soviet Union, 1940-1941. Berghahn Books.

Klimov, G. (1953). The Terror Machine - The Inside Story Of The Soviet Administration In Germany. Praeger Publishing.

Korostelina, K. (2010). War of textbooks: History education in Russia and Ukraine. Communist and Post-Communist Studies, 43(2), 129–137. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.POSTCOMSTUD.2010.03.004

Kuromiya, H. (2014). Stalin's Great Terror and the Asian Nexus, Europe-Asia Studies, 66:5, 775-793, DOI: 10.1080/09668136.2014.910940

Lukas, J. (2001). The Last European War: September 1939 - December 1941. Yale University Press.

MacKenzie, D. & Curran, M. W. (2002). A History of Russia, the Soviet Union, and Beyond: 6th edition. Wadsworth.

Martin, T. (1998). The origins of Soviet ethnic cleansing. The Journal of Modern History, 70(4), 813–861. https://doi.org/10.1086/235168

Morris, J. (2004). The Polish Terror: Spy Mania and Ethnic Cleansing in the Great Terror. Europe-Asia Studies, 56(5), 751–766. https://doi.org/10.1080/0966813041000235137

Mulligan, T. P. (1988). The Politics of Illusion and Empire: German Occupation Policy in the Soviet Union, 1942-1943. Praeger.

Snyder, T. (2012). Bloodlands: Europe Between Hitler and Stalin. Basic Books.

Synder, T. (2007). Sketches from a Secret War: A Polish Artist’s Mission to Liberate Soviet Ukraine. Yale University Press.

Stalin, J. V. (1945). Toast to the Russian People at a Reception in Honour of Red Army Commanders Given by the

Soviet Government in the Kremlin on Thursday, May 24, 1945. Marxist Internet Archive. https://www.marxists.org/reference/archive/stalin/works/war/index.htm

Tooze, A. (2008). Wages of Destruction: The Making and Breaking of the Nazi Economy. Penguin Books.

Weinberg, G. L. (2005). A World at Arms: A Global History of World War II. Cambridge University Press.

Wesolowsky, T. & Luxmoore, M. (2019). Molotov-Ribbentrop What? Do Russians Know Of Key World War II Pact? Radio Free Europe Radio Liberty. https://www.rferl.org/a/molotov-ribbentrop-what-do-russians-know-of-key-wwii-pact/30123950.html

RSS Feed

RSS Feed